Why Cambodia Became a French Protectorate

Being located on the Mekong river was both a blessing and a curse for Cambodia. It was a blessing because this incredible river fed, and still feeds, the Tonle Sap, a lake that is now thought to contain more fish than any other inland body of water in the world and which, with its practically inexhaustible reservoir, keeps the land in the Mekong Delta – which was in the 19th century a part of Cambodia – constantly fertile, turning it into one of the ‘rice bowls’ of Asia. It was a curse because it was exactly this fertile land that attracted the envy and greed of other, more powerful nations: Siam, now Thailand, and Vietnam both wanted to conquer Cambodia. After all, since the 15th century, the Khmer Empire had been losing more and more power and influence, to such an extent that it would have been easy prey if their neighbours had been able to agree on who should control the Mekong Delta.

A Stalemate But No Solution

This war had already driven Ang Duong, father of Norodom I, to Bangkok, where he spent 27 years as a guest and hostage of the Siamese court, researching and publishing the history of his home country; the place he had married, raised children and witnessed the war between Vietnam and Siam destroy his Cambodia.

Norodom was already 14 years old when his father finally established himself as King of Cambodia, and that was only possible because Siam and Vietnam had reached a stalemate. Neither country was able to defeat the other. An independent Cambodia under Ang Duong was, as far as both nations were concerned, a temporary compromise, which would last exactly as long as it took before either Siam or Vietnam tried to attack again.

A New Power Enters the Stage

And so, Ang Duong knew that he would need a clever, well trained heir to succeed him. He sent his eldest son to Bangkok to study and serve in the army there. And yet, when Ang Duong died as early as 1860, his 26-year-old son didn’t even get to be crowned. The Siamese had possession of the Cambodian royal regalia and were refusing to give it back. Then riots started breaking out and Norodom had no choice but to flee to Bangkok like his father before him.

Meanwhile, the French Empire had decided to establish a colony in Cochinchina. In 1859, a few dozen French ships carrying 3,000 men arrived in Vietnam, whereupon the French conquered Saigon and established themselves as the new power.

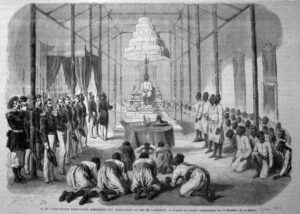

And so, for the first time, there was a real alternative for Norodom. He negotiated with the French, who were more than happy to discuss his proposals; after all, a treaty would provide the perfect way to establish themselves in Cambodia. On 11 August 1863, both sides signed a sort of friendship treaty. Cambodia would remain an independent monarchy but would grant the French extensive control over the country’s trade and military defences, which would be exercised by the French Résident Supérieur.

Cambodia. Norodom I. Piaster 1860, Paris. Very rare, especially in this condition. PCGS MS64. Nearly FDC. Estimate: 12,500 euros. From Auction 339 (2020), No. 1258.

An Opportunity for Norodom – and for Cambodia?

This is the historical background of this coin by Norodom I, which will come under the hammer in the Künker Auction 393 on 29 September 2020 under lot number 1258. This coin is dated 1860 but was actually produced in 1864 in Paris. The year indicated on the coin refers to Norodom’s ‘official’ ascent to the throne, right after the death of his father. It bears witness to Norodom’s hope that, with the help of the French, he would modernise his own country and therefore secure his place in the world. An important step of this modernisation was to establish a European-style currency.

The obverse depicts the King of Cambodia, Norodom I. The inscription is in French; under the neck truncation, it reads FACONNET for the die cutter, who was responsible for the portrait. On the reverse, we see the coat of arms of Cambodia as well as the nominal value of the coins in three language: French, Spanish and Cambodian. The coat of arms of the Kingdom of Cambodia is positioned in the centre of the coin: it consists of two ‘phan’ (ceremonial bowls) stacked on top of each other, with a golden sword resting on top, and framed by a laurel wreath adorned with the royal order of Cambodia. The coat of arms is topped with the shining royal crown.

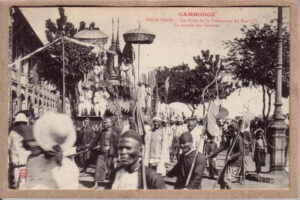

These coins were produced in a far too low a mintage to play any kind of role in circulation. But they hark back to what was initially a good time, during which many reforms were implemented. The administrative and legal systems were reformed, monopolies and slavery were abolished, the costs of the royal family were drastically reduced. Norodom promoted traditional dance and the fine arts. Yes, the French even made it possible for Norodom to be crowned in 1868, and with the right regalia too, as Siam was forced to return it.

An Abrupt End

But of course, the French had their own agenda, specifically their own colonial empire in Southeast Asia that they could exploit to their hearts’ content. In 1887, they founded Cochinchina. Norodom remained King of Cambodia in name, but he didn’t have any power of his own. He died in 1904 without even managing to secure his son’s succession to the throne. This son was far too intelligent for the French and far too well known in the parlours of Paris.

A Crown Prince who had openly defended slavery in the French newspaper ‘Le Figaro’ with the words: ‘We have our slaves, but your workers have the freedom to starve,’ was not someone to be entrusted with the delicate task of running a country.

Here you can read the detailed preview of the auction in which this coin will be sold.

And here you can find out more about Norodom I and the French protectorate over Cambodia.

In this article you can read about the history of Cochin-China.

And this is quite the book you need, if you are interested in Coins and tokens of French Indochina.