The Last Years in the Life of Jacques-Antoine Dassier

On 3rd August 1765, Jacques-Antoine Dassier signed a contract engaging him to go to Russia as a medalist. What had led to this point? Why did Empress Elizabeth, the daughter of Peter the Great, choose a medalist from Geneva, out of all possibilities, to design coins and medals at her court?

How to Make Friends at Court

A Genevan goldsmith by the name of Jérémie Pauzié who worked at Elizabeth’s court has left us with his version of the occurrences. In his memoirs, he recounts traveling back to his old hometown in the years 1750 and 1751. In Geneva – then a hub of the luxury industry – he took the opportunity to do some extensive shopping. He knew quite well that Genevan products like watches and jewelry would be met with strong demand back in Russia. One destination during his shopping spree was the studio of Jean Dassier, at the time already 84 years old, where he bought numerous medals. These were to help Pauzié win over the essential decision-makers in order to gain employment for his own son.

Back in Petersburg, Pauzié went to the court. He was greeted by Ivan Ivanovich Shuvalov, a favorite and lover of the Empress, who immediately wanted to see what Pauzié had brought from Geneva. Pauzié showed him Dassier’s medals, and Shuvalov was delighted. “If the Empress sees those, Her Majesty will buy them immediately”, he is quoted. Consequently, Pauzié gifted the medals to Shuvalov (certainly not without ulterior motives) and said he had brought a second set for Her Majesty.

Not surprisingly, Pauzié was received by the Empress straightaway, who was eager to see the precious things brought from Geneva. Pauzié laid them out before her: a golden egg trimmed with gemstones in the form of the imperial double eagle and Elizabeth’s name, a pretty pendent and a ring bearing a tiny watch by Jean-Jacques Pallard inside. The Empress was in raptures, asked to see the invoice and, without hesitating, agreed to the requested 12,000 rubles. To give some perspective: A teacher at the Academy of Arts founded by Shuvalov made only 1,000 rubles a year. After that, Pauzié reportedly gifted her the medals from Dassier’s workshop. He describes Elizabeth as being so thrilled that she insisted on having Dassier at her court.

Jacques-Antoine Dassier’s portrait of Montesquieu shaped our image of this great thinker. Anonymous painting from the end of the 18th century.

A New Cultural Policy for Russia

We don’t know if this is how things actually happened, or if Pauzié just wanted to earn the praise for bringing Dassier to Saint Petersburg. Either way, his appointment went hand in hand with Shuvalov’s cultural policy which, more than before, was based on the French-speaking regions.

To his contemporaries, Ivan Ivanovich Shuvalov was the patron of Russian Enlightenment. He stood in correspondence with Voltaire and the editors of the Encyclopédie, Diderot and d’Alembert; he supported Mikhail Lomonosov in the founding of a university in Moscow; he initiated a Russian newspaper and dreamed of establishing an art academy in his own palace.

One of the teachers he brought to Russia for this purpose was in fact the son of Jean Dassier, Jacques-Antoine Dassier, at the time most certainly among the most well-known portraitists and die-cutters in all of Europe. He belonged to a famous Genevan dynasty of die-cutters who made their living by creating numismatic works of art collected all over Europe. Their medal suites on the famous reformers, on the celebrities of the Louis XV era, on the British kings or on Roman history – just to name a few – were bestsellers. Only three years earlier, Jacques-Antoine Dassier had captured the attention of the educated society with his depiction of near-blind Montesquieu, which was considered to be genius.

Thus, his appointment to the Petersburg court – whether with or without the aid of Pauzié – was definitely a coup.

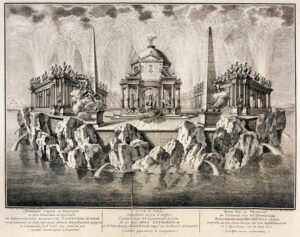

A court festival with fireworks under Catherine the Great, organized by Jacob Staehlin, on June 28, 1763.

Chief Engraver of the Saint Petersburg Mint

Dassier’s direct superior was not Shuvalov, but Jacob Staehlin from Swabia. In today’s words, we would probably best describe his tasks as what is known to us as marketing and PR. For example, Staehlin created the impermanent wooden triumphal arches and decorations that were needed for all celebrations of moving out and in. He created the drafts for emblems and tomb monuments. He also thought up such fleeting works of art like the Baroque fireworks which were an indispensable element of every court festival. He represented what we would nowadays call corporate identity – making sure that the Empress’s appearance was always flawless, whatever the circumstances.

His tasks included supervising the production of coins and medals and defining the inscriptions and motifs, and thus, he became Jacques-Antoine Dassier’s superior. We know that the two artists got along perfectly. And thanks to Staehlin’s writings, we are very well informed about Dassier’s work.

After his arrival, Dassier worked on three projects simultaneously: on a nowadays extremely rare medal for his patron Shuvalov, on a die for ruble pieces and on the die for the item that is offered at Künker on 28th January 2021 – a 10-ruble piece from 1757.

Dassier’s Tasks and Income

Dassier had not been employed just to make dies. His two-year contract specifically stipulated that he should teach “the art of engraving coins and medals to as many Russian students as required”. For this, he was paid 2,500 rubles a year, plus 250 Dutch ducats to cover travel expenses, and another 500 rubles for paying an assistant who would support him in his work. Besides, he probably enjoyed free lodging.

After two years, Dassier renegotiated. He now received a yearly salary of 3,000 rubles, plus 500 rubles for every die he completed. This is all the more astounding as it turned out that, due to his ever-worsening tuberculosis, Dassier was in fact unable to teach young artists on a regular basis.

Instead, Staehlin and Shuvalov discussed his participation in a medal suite of 150 to 180 items, dedicated to the achievements of Peter the Great.

By that time, though, Jacques-Antoine Dassier was already so severely ill that he wished to return home. In the fall of 1759, he boarded an English ship, but only made it to Copenhagen. Testimony of his importance is the fact that the Danish Prime Minister himself accommodated Dassier in his own home, where he died on 21st October 1759.

An Exquisite Provenance

The coin offered by Künker, testimony of Jacques-Antoine Dassier’s activities in Russia, was once part of the collection of Count (and numismatist) Emeryk Hutten-Czapski, as we can see from the collector’s hallmark. This well-known Polish nobleman, who gave his name to the numismatic museum of Krakow, the “Emeryk Hutten-Czapski Museum”, worked in the Russian administration. During his stay in Russia, he gathered an extensive collection of Russian coins and medals, which he sold between 1882 and 1884 in order to expand his specialty field, Poland.

By the way, in 2017 Künker offered a ruble of Peter the Great dated 1707 from the Hutten-Czapski collection. In 2019 there was a set of three platinum coins from the Hutten-Czapski collection in a Künker sale. The ruble sold for 290.000 euros, the platinum set for 750.000 euros. Which price will the Dassier 10 ruble piece score? We shall see…

Here you can read a comprehensive auction preview.

You can browse the complete auction catalogue on the Künker website.