Sir Frederick Henniker: Notes during a visit to Egypt…

by Claire Franklin

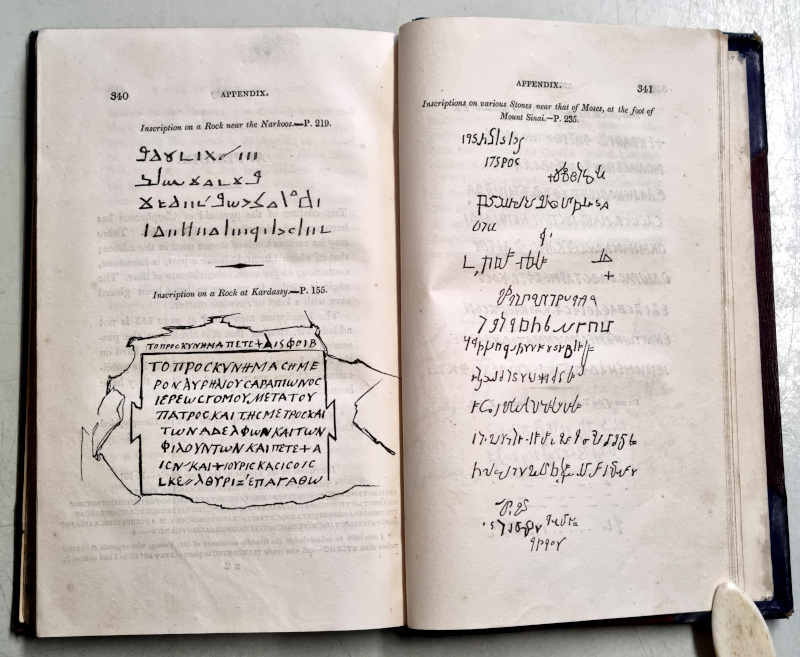

An almost 200 year-old travel book describes the world in a very different manner to how we would today, but of course that is what makes a description like this so interesting. For later readers with historical and numismatic interests, a work like this offers many insights into early tourism and the antiquities trade in Egypt, Nubia and Palestine with descriptions of archaeological sites including Cairo, Jerusalem, Baalbek (Balbec), Mount Sinai, and many more.

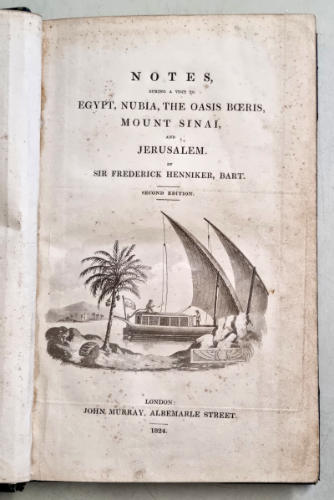

Sir Frederick Henniker (1793-1825), 2nd Baronet of Newton Hall, Great Dunmow in Essex, was a minor English aristocrat. After graduating from St. John’s College, Cambridge, with a BA in 1815 and succeeding his father, Sir Brydges Tregothick Henniker, as baronet in 1816, in his early twenties he embarked on a journey which took him through Europe and the Near East, visiting Jerusalem and finally arriving in Egypt. In his account, published in 1823 with a second edition in 1824, we see the world through a precociously learned, but still young and somewhat immature narrator, writing in an often sketchy manner, but full of humour and insight, who proclaims, „Whenever I make use of Arabic terms, I shall write them as my ear dictates to my pen“ (p. 7). This sense of humour is present throughout the work; upon arriving in Antinoe, where Hadrian’s favourite Antinoos died, he remarks, „if (Antinoos) had known that his voluntary and personal sacrifice would have been commemorated in such a manner, he could not have fixed upon a more eligible spot“. (p. 93). Henniker also notes, „coins in great quantities are to be found here, which the Arabs are glad to exchange for paras with foolish ignorant Francs. This old money won’t purchase bread.“ (p. 95).

Throughout his diary, Henniker comments on the impact which the European trade in antiquities is having on the archaeological sites. On visiting the Nile, he writes, „The obeliscs of Cleopatra do not appear striking to one accustomed to those at Rome…one of them is under sailing orders for London“ (p. 11). Cleopatra’s Needle, now on the Victoria Embankment in London, which was given to Britain by Muhammed Ali Pasha in 1819, did not actually leave Egypt until 1877, due to the cost and considerable logistical problems facing the transport. At Rosetta, Henniker encountered a similar situation: „The trilinguar stone that was discovered here is to be found now in the British Museum; no object of curiosity remains except the gardens. I wish that they were in London too“ (p. 21). The Europeans‘ craze for antiquities was sometimes baffling to the local inhabitants. Henniker wrote that at Sais, the Arabic inhabitants told him that „Francs, foolish Francs, come there to buy whatever is found“. Only one statue was left, and that was because „not even an English-man can move it“ (p. 27). Nevertheless, there were clearly efforts to meet the European demand for antiquities: „Distant about three hours from Alexandria, labourers are making excavations in the sand, they call it Canopus; I saw no fruit of their industry, but I am told that whatever is found, is again hidden, till a sufficiency is collected for the market.“ (p.18). Elsewhere, Henniker writes that the local Egyptians assumed that the Europeans were only interested in collecting mummies because of the gold hidden in them.

The account shows that although ever-increasing numbers of European travellers were making their „Grand Tours“ of the Near East, the journey was not without considerable dangers and difficulties, even for a man like Henniker, who was wealthy and well-equipped (he even possessed a newly-invented Davy safety lamp, p. 98). The journey takes place in the shadow of a plague, of which Henniker writes, „nothing certain is known of it except its dreadfulness- fear, as in all other countries, and other diseases, is a conductor“. (p.8). Henniker outlines the difficulty of finding local guides for stages of his journey, describes his attempts to hide his Christian European origin, and frequently recounts his attempts at bargaining. Even his attempts at sketching what he saw- another activity beloved of early travellers- led to problems: „I commenced a sketch- all my subjects ran away shrieking- the villagers imagined I was writing charms“. (p. 33).

Henniker has a keen eye for unusual events and scenes, even when his enthusiasm for visiting yet more ancient ruins sometimes deserts him; in the Nile Delta, he describes how he nearly sank in the alluvial mud deposits, while a travelling companion, a soldier, „being a very heavy man, was fairly planted; had thoughts of leaving him there“ (p. 30). On another occasion, while visiting the pyramids, he and his travelling companion come to the conclusion that they are „nothing more than a pile of bricks“ (p. 75). Henniker contrasts the Islamic tradition of aniconic art with that of Europe- „What would they think of our statues of men celebrated (in general) for destroying(?)“ (p. 59, footnote).

Frederick Henniker, for all his cheerfulness, was not blessed with good fortune. On his way from Jerusalem to Jericho he was robbed and left naked and wounded, and although he returned to Britain and canvassed as a political candidate for Reading, he died in 1825 aged only 32. What he left, was this travel guide- a product of its times, but a good-natured and very readable insight into the beginnings of cultural tourism and the 19th century antiquities trade.

Fr. Henniker, Notes during a visit to Egypt, Nubia, the Oasis Boeris, Mount Sinai, and Jerusalem. 2nd Edition, London, 1824, X+352 pp. A copy of this work will be up for sale in Münzen & Medaillen, Auction 50, held in Weil am Rhein on 27th June 2023, as Lot 1136. A copy of the sales catalogue may be obtained from M & M GmbH, Hauptstraße 175, 79576, Weil am Rhein, Germany.