French History in Coins – Part 2: From the Second Republic to the Second Empire

written by Aila de la Rive, by courtesy of the MoneyMuseum, translated by Maike Meßmann

In our series “French History in Coins”, we examine different chapters of French history and present the coins and banknotes of that period. After having explored the late 18th and early 19th centuries in our last article, we will today venture into the 19th century – on a journey from the Second Republic to the Second Empire.

Content

From the Second Republic to the Second Empire

In the 19th century, the industrialisation and modernisation of the agricultural sector brought about far-reaching social change. Across Europe, hunger and poverty drove people to leave the countryside in the hope to find better opportunities in the cities. Paris – which was already home to a million people around 1850, making it one of Europe’s largest metropolises – had to accommodate a particularly large share of new citizens. People huddled in an almost impenetrable clutter of huts and tenements in the old town; many rooms were rented out in shifts to various tenants.

The city’s facilities were collapsing given the sheer amount of people. Ever new cholera epidemics caused by the Seine’s contaminated drinking water claimed tens of thousands of victims. Discontent grew – not just among the poor.

Thus, uprisings and riots were nothing but daily business in Paris: since 1827, barricades had been built in the city eight times; three times they were the vanguard of a revolution. In 1848, myriads of craftsmen, workers and students took to the street again to demand reforms and better living conditions. When government troops opened fire on the demonstrators, the local uprising turned into a national revolt. 2,000 barricades were built in Paris; all barracks and arsenals fell into the hands of the insurgents. The King, Louis Philip I (1830–1848) escaped from Paris; his throne was publicly burned on a Paris square. On 24 February, the Second French Republic was proclaimed.

As early as a few months later, elections took place in France. Thanks to the introduction of universal male suffrage – women were not allowed to vote until 1944 – the number of those eligible to vote jumped from 250,000 people to more than nine million. With a turnout of more than 80 percent, these Frenchmen elected Louis Bonaparte, the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, President of the Republic in December 1848. Louis Bonaparte (1848–1870) turned out to be an unpleasant surprise for his republican electorate: he followed in his uncle’s footsteps. In 1851, he staged a coup d’état and had himself made President for life; exactly one year later, he had himself proclaimed Emperor of the French as Napoleon III after a referendum. The Second Republic was replaced by the Second Empire.

The Coins of the Second Republic and the Second Empire

In the 19th century, the propensity for paper money that had emerged in the previous century grew stronger throughout Europe; coins increasingly took a back seat. In France, banknotes of the Banque de France became legal tender. However, during the 1848 revolution, they lost their convertibility: the state treasury was short of gold – and the idea behind convertibility is simply that the government is obliged to exchange circulating banknotes for gold at a fixed rate at any time. For these purposes, central banks always held a certain amount of gold reserves.

Kingdom of France. Charles X (1824–1830). 40 francs, 1828, Paris. Gold. From Gorny & Mosch auction 171 (2008), lot No. 4630.

Although coins were minted on behalf of the Second Republic, people hoarded them and banknotes made up the lion’s share of all circulating money. The coins itself changed and reflected historical developments. Under Louis XVIII and his successor Charles X (1824–1830), the reverse showed the old coat of arms of the House of Bourbon. The 40-franc piece by Charles X depicted here was worth quite a lot of money at the time, as is evidenced by the amount of taxes paid by the electorate: during the Bourbon Restoration in France, only those were eligible to vote who paid at least 300 francs in direct taxes a year. Of the total population of almost 30 million people, only about 100,000 men fulfilled this requirement. The bourgeoisie demanded the government to soften this excessive requirement and to expand the franchise; the minister Guillaume Guizot (*1787, †1874) responded: “There will be no reform. Enrich yourselves, and you will be eligible to vote.”

When Charles X disbanded parliament in July 1830, introduced even stricter rules to the electoral law – from then on, the right to vote was basically reserved to big landowners – and increased censorship of the press, the July Revolution broke out in Paris. Charles had to flee, Louis Philippe from a side-line of the Bourbon family was proclaimed king (1830–1848). The franchise was expanded to include all men who paid at least 200 francs in taxes per year, but this still meant that the electorate included less than half a million men. Small proprietors, artisans, peasants and workers – as well as women – did not have any political rights. In 1846, an agricultural and economic crisis hit: two poor grain harvests led to supply shortages and caused the price of grain to jump from 17 francs per hectolitre in 1845 to 43 francs in the next year. Industrial production declined, wages fell, unemployment rose – in some regions, such as Normandy and Champagne, by up to 35 per cent. There were riots throughout the country; the bourgeoisie tried to use the crisis to finally push through an expansion of the franchise. In February 1848, mass protests and street battles forced the king to abdicate.

Kingdom of France. Louis Philippe (1830–1848). 2 francs, 1848, Paris. From Künker auction 254 (2014), lot No. 2132.

Under Louis Philippe, coins only showed an oak wreath with the denomination on the reverse; and, incidentally, the depicted 2-franc piece corresponds to the average daily pay of a Paris factory worker. A male worker, mind you. After all, women earned as few as 60 centimes for the same work, children got 53 centimes a day. The price of bread, however, is the same for everyone: about 40 centimes per kilogram.

Second French Republic (1848–1852). 1 centime, 1850, Paris. From Künker eLive Auction 46 (2017), lot No. 514.

After the 1848 revolution and the abdication of the king, coin designs went back to the well-known Hercules group and other depictions of liberty. The so-called Phrygian cap on the depicted centime is one such age-old symbol of liberty. French women and men had started to wear red Phrygian caps as early as in the 1789 revolution. The headgear is originally from ancient Phrygia in Asia Minor, where such caps with the apex bent over were worn by freed slaves. The liberty cap is depicted on coins of various countries: in addition to French issues, it can also be seen on US coins.

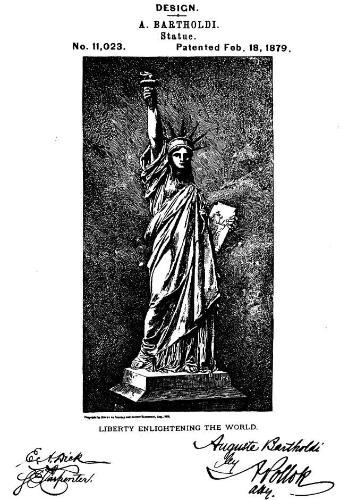

The French sculptor Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi had his draft for the Statue of Liberty patented in the US in 1879.

And yet there were also republicans who considered the Phrygian cap too revolutionary a symbol and were of the opinion that the personification of a legitimate and peaceful republic ought to wear a more classic headgear – for example a laurel wreath. Although this idea did not establish itself, we owe some designs to it that still exist today, such as the crown of the Statue of Liberty with its seven rays, designed by the French sculptor Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi (*1834, †1904).

Second French Republic (1848–1852). 5 francs, 1850, Paris. From Künker auction 296 (2017), lot No. 1559.

Be it liberty cap or laurel wreath, the symbol had to be based on an ancient model. The Italian goddess Ceres depicted on the 5-franc piece of 1850 wears a highly elaborate wreath of leaves, flowers and ears. Ceres had already been depicted on coins in the 5th century BC; today and back then, the goddess represents the growth of plants and the fertility of the country. As a legend, the reverse features the motto of the revolution: “LIBERTE EGALITE FRATERNITE” (Liberty, Equality, Fraternity).

In the next part you will find out about the economic heyday of the Second Empire and the founding of the Latin Monetary Union in Paris.