Smithsonian Acquires Largest Collection of Charleston Slave Badges

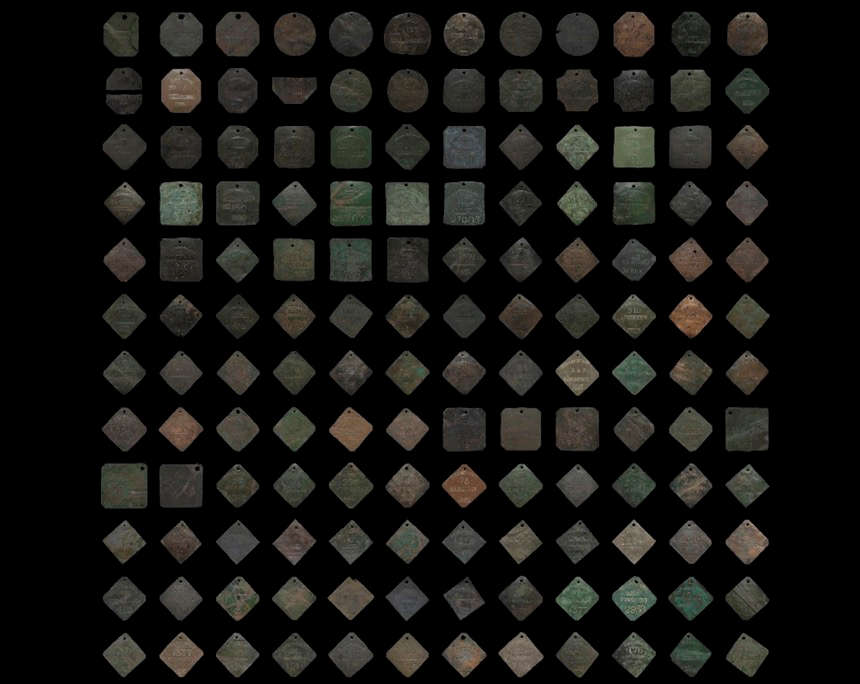

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture recently acquired what is thought to be the largest and most complete set of historic Charleston Slave Badges. The collection includes 146 rare badges dating as far back as 1804. It also features badges with makers’ marks and two with personalized inscriptions. To share the stories of these objects with a worldwide audience, the museum has launched a Searchable Museum feature, which tells the historical significance of Charleston Slave Badges and the museum’s recent exciting acquisition.

“We are honored to share the story of enslaved African Americans who contributed to building the nation,” said Mary Elliott, NMAAHC museum curator. “It is a story that involves the juxtaposition of profit and power versus the human cost. The story sheds light on human suffering and the power of the human spirit of skilled craftspeople who held onto their humanity and survived the system of slavery, leaving their mark on the landscape in more ways than one.”

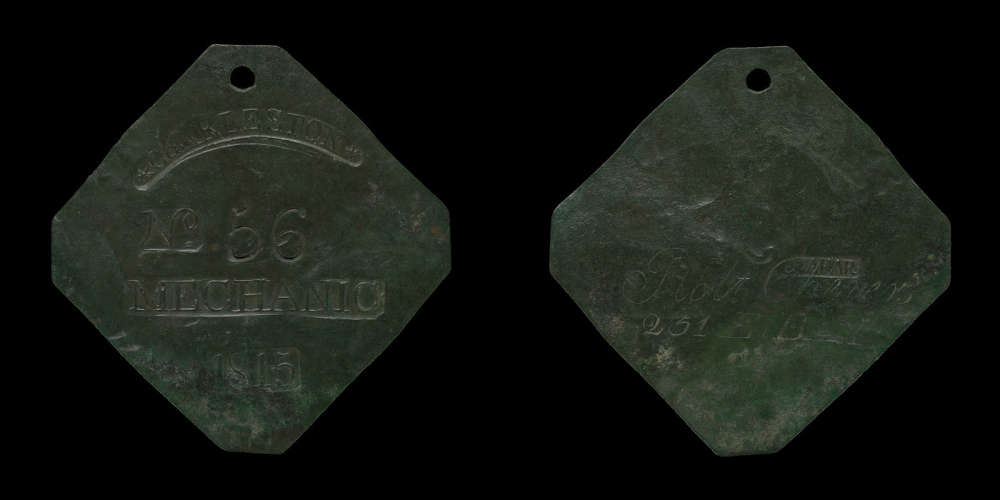

Charleston slave badge from 1815 for Mechanic No. 56 named Robert Cheevers. From the Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Through this digital offering, visitors can engage with the objects and learn about the legislated system of leased enslaved labor in Charleston, South Carolina, those who profited from the system and how enslaved African Americans navigated the landscape of slavery using their abilities, skills and intellect. In addition to providing the history of Charleston Slave badges, the new Searchable Museum feature will provide insight into collecting, archaeology, the role of vocational training and the meaning of freedom.

Charleston slave badge from 1841 for Porter No. 136 for Boy Sam. From Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The Slave Badge system was initially legally instituted in Charleston in 1783 as a form of control and a source of profit. The badge system required that enslaved African Americans whose labor was leased out by their enslavers wear registered identifying badges. The badges identified the occupation of the enslaved laborer, whether as a skilled craftsperson or a servant. It was a form of control and surveillance over African Americans who had limited autonomy to move about the city conducting work – but today they are reminders that the enslaved were skilled workers who built much of Charleston.

Charleston slave badge from 1803 for Servant No. 624. From the Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Enslavers paid a registration fee to the city for each enslaved person whose labor they leased out and, in turn, the city provided the badges that registered leased enslaved laborers were required to wear. Enslavers profited from money earned leasing out the labor of skilled African Americans, while the city received profit and gained the benefit of the skilled work of enslaved African Americans who, essentially, built Charleston’s urban landscape.

Charleston slave badge from 1800 for Fisher No. 14. From the Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Enslaved African Americans, bearers of the slave badges, served in various capacities as indicated by the badge labels, including skilled mechanics, porters, fishers, fruiterers, carpenters, porters and servants. Although the badges served as a form of control, those who wore them had some degree of autonomy to move about the city while conducting work. This provided greater opportunities for communicating with a wider network of enslaved Black people. In some instances, they were also able to keep some of the money earned from their labor, which helped toward purchasing freedom for themselves and loved ones.

Charleston slave badge from 1820 for Servant No. 375. From the Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The recently acquired historic collection was compiled by renowned collector Harry S. Hutchins Jr., who, along with co-authors Brian E. Hutchins and historian Harlan Greene, wrote and published the book Slave Badges and the Slave Hire System in Charleston, South Carolina, 1783–1865, which is highly regarded among collectors.

Charleston slave badge from 1811 for Carpenter No. 27. From the Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Hutchins dedicated his life to collecting slave badges, expressing that he felt it was important to tell the story of the skilled craftspeople. When presented with the opportunity to draft the credit line for the collection, Hutchins provided the following text “Partial Gift of Harry S. Hutchins, Jr. DDS, Col. (Ret.) and his Family, dedicated to the individuals these Slave Hire Badges represent and their descendants.”