Royal Gold: England’s Five Guineas and the English Gold Currency

by Ursula Kampmann, on behalf of NGSA

In auction 21 on 10 December 2024, Numismatica Genevensis will present a complete private collection of Five Guineas. The ensemble includes coins from all the years in which this denomination was issued. It is therefore the only complete run of Five Guineas in private hands. The quality and the preservation of all the pieces is truly exceptional! Every Five Guineas is a work of numismatic art in gold, harking back to a time when gold became the main coinage metal in England, ushering the era of the gold standard. This article tells the story of a fascinating denomination.

Content

Let us first clarify a few terms before things get confusing. When we refer to a gold currency in this text, we mean a monetary system in which gold coins play a dominant role. We are not referring to a gold standard, where banknotes serve as legal tender backed by gold reserves. Britain only introduced that in the 19th century. Additionally, for the sake of consistency, we will stick to the term “England,” even though from 1707 onwards one could also speak of Great Britain.

No. 2002. Charles II, Five Guineas 1668. Only 128 specimens known. NGC MS61 (highest grade NGC). Estimate: CHF 50,000. Photo: Lübke + Wiedemann KG.

A New Chapter With New Technology

When Charles II returned to London on 29 May 1660, the entire country was ready for a new beginning. The king had spent time in various countries during his exile and brought with him fresh ideas. And thanks to royal support, French engineer Peter Blondeau, who had been campaigning to modernise coin production at the mint in London since the 1650s, finally got his way. Rolling mills and screw presses were purchased to make the transition to machine-minted coins. This technical innovation was accompanied by a currency reform. On 27 March 1663, a coinage ordinance was passed, making the guinea the official coin of 20 shillings. The coins were minted with the denominations of a half guinea, a full guinea and two guineas. In 1668 the five-guinea piece was introduced as the heaviest coin in the series with a weight of 41 g. Today it is regarded as the quintessential royal coin, the most beautiful representational gold issue struck for circulation purposes in England.

The new technical possibilities solved a problem that had caused great difficulties for the English economy: fraudsters of all kinds had systematically engaged in the activity of coin clipping off the edges of English coins that were made of precious metal. Thus, the weight of the coins was steadily decreasing. Domestically, a coin was worth its face value. But internationally it was worth its silver content. Merchants therefore always faced a currency risk.

Peter Blondeau solved this problem by putting an edge inscription on all guinea coins, including the Five Guineas. The exact process of how he created this technically complex security feature was kept secret. After all, the edge inscription “Decus et Tutamen”, taken from the Aeneid, described the very purpose of this lettering: to decorate and to protect the gold coins at the same time. Issues with edge inscriptions could no longer be clipped unnoticed and were almost impossible to counterfeit.

Gold from Africa

Some of the gold for these coins probably came from Africa, where the Royal African Company, established by Charles II in 1660, had a monopoly on trade. The king was to receive half the profits. However, there were hardly any profits in the beginning. The Royal African Company was dissolved in 1672 and replaced by a successor company with much broader powers: the Royal African Company of England had the right to build forts and to impose martial law to enforce its economic interests in the gold, silver and slave trade.

No. 2023. Jacob II. Five Guineas 1687. Only 38 specimens known. NGC MS61+. Estimate: CHF 50,000. Photo: Lübke + Wiedemann KG.

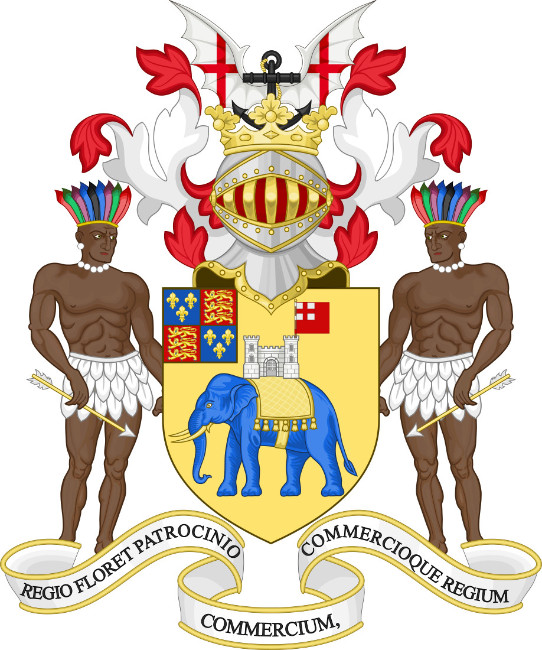

The small elephant that can be seen on some guineas of Charles II and Jacob II is thought to refer to the Royal African Company and its successor. The elephant is depicted with and without castle on its back. In the second case, it is the same elephant depiction that appears in the coat of arms of the RAC.

As most of the gold trade took place in the Gulf of Guinea, it is said that the English gold coins were referred to as guineas because of this – at first only colloquially. The first written evidence of the name was found in a document dated 1718.

No. 2033. William III. Five Guineas 1700. Only 45 specimens known. NGC MS62. Estimate: CHF 50,000. Photo: Lübke + Wiedemann KG.

The Silver Crisis and the Gold Standard

Charles II made a serious mistake in his coinage reform: he did not order that the old, much lighter silver money be withdrawn from circulation. Therefore, old silver coins continued to circulate alongside the full-weight new silver money. In fact, it would be more accurate to say that the new silver money did not circulate at all. Those lucky enough to get a full-weight silver coin from the mint put it under the mattress or had it melted down. This was the only sensible thing to do as the coin’s material value exceeded its face value.

This meant that there were almost only poor silver coins in circulation, and these bad coins drove out the good new money. Today this phenomenon is known as Gresham’s law. As a result, the premium that money changers charged for gold coins kept rising. In 1695, the price of a guinea rose by 35% in six months. At times, the price of a one-guinea coin is said to have been as high as 30 shillings.

This spurred the government into action. But how could a new exchange rate between gold and silver be established? Various approaches were put forward. The finance minister’s proposal was for the value of coins to be in line with the market price. As a result, silver coins would have increased in value and the value of gold coins would have decreased. King William III took a different view. He convinced the philosopher and economic theorist John Lock to argue in his favour. The latter wrote that money could not be fixed by a monarch or a parliament, but that money was an unchangeable unit of value that had to be above the law. In the end, another of his arguments proved more convincing: he told MPs that a devaluation of gold coins, which were the main currency in circulation, would drastically reduce their fixed income. As many MPs lived on this money, this would have meant a significant loss of income for them. So they went along with Locke’s view and stuck to the old standard.

But this meant that gold continued to be overvalued by the mint, and silver undervalued. The state lost money with every silver coin it produced. Therefore, whenever possible, silver coins were not minted at all. The amount of gold coins such as guineas, on the other hand, increased as the state made good money from them. By 1701, there were 9.25 million pound worth of gold coins in circulation. This exceeded the value of the gold coins that had been in circulation before the coinage reform by a third, and marked the first step towards a gold currency.

No. 2035. Anne. Five Guineas 1703. From the gold of the Vigo loot. Only 5 specimens known. NGC UNC Details obv. tooled. Estimate: CHF 150,000. Photo: Lübke + Wiedemann KG.

The Vigo Loot

The rare coins of Queen Anne featuring the legend VIGO on the obverse are among the most iconic British coins. They commemorate a naval battle fought during the War of the Spanish Succession in which the English plundered much of the wealth of the Spanish treasure fleet. Unfortunately, we do not know how much they took. And, in fact, opinions on this matter have changed over time.

While it was previously thought that all the silver had been transported to England, we now know that a large part of the silver had been unloaded before the English attacked the fleet. The English only took the private possessions of those who had paid for cargo space on the ship. Pepper, cocoa, tobacco, furs, indigo, cochineal and so on were at least as valuable as gold and silver. But these items did not belong to the Spanish king but to investors in Amsterdam and England, which led to mixed feelings about the “victory” at Vigo Bay, especially among the English.

When examining Queen Anne’s coinage, we should therefore see it in the light of propaganda. The coins were intended to show citizens that the battle had been worthwhile. In fact, Isaac Newton, then director of the mint, recorded exactly how much metal he received from the Vigo loot: as few as 4504 pounds and 2 ounces of silver (= 2,043 kg) as well as 7 pounds, 8 ounces and 13 pennyweights of gold (= 3.4 kg). He had 14,000 pounds worth of coins struck from this metal, and these are now among the rarest and most sought-after British coins.

No. 2038. Anne. Five Guineas 1706. Only 94 specimens known. NGC MS63 Top Pop. Estimate: CHF 75,000. Photo: Lübke + Wiedemann KG.

The Methuen Treaty

The victory at Vigo Bay cemented England’s importance as a naval power. Portugal, fearing for its overseas territories in the War of the Spanish Succession, thus concluded a treaty with England in 1703 that would also affect the English gold currency. The Methuen Treaty was not only a military agreement but ensured that Portugal was allowed to import wine into England and that England could export textiles to Portugal. And since it was cheaper to acquire anything by means of gold in England, large quantities of Portuguese gold coins poured into the country, some of which were melted down and struck into new coins at the Royal Mint. The increase in gold coins accelerated the transition to an economy that was based solely on gold coins.

No. 2044. George I. Five Guineas 1717. Only 13 specimens known. NGC AU55 Top Pop. Estimate: CHF 25,000. Photo: Lübke + Wiedemann KG.

Sir Isaac Newton’s Fight to Stop Counterfeiting

Between 1699 and 1727, Sir Isaac Newton was in charge of Englands’s coinage. He was appointed Warden of the Royal Mint in 1696 and was told that the job was a lucrative position without much responsibility. Newton thus moved to London.

But the years between 1696 and 1699 saw what history calls the Great Recoinage. Old silver coins were to be completely withdrawn from circulation and replaced by coins of the correct weight. Gold coins, however, remained valid. The old silver coins were withdrawn throughout the country. As Warden of the mint, Newton checked their fineness and weight. He was horrified to discover that about 20% of the coins were counterfeit.

At the end of the 17th century, counterfeiting was one of the most serious capital offences, punishable by hanging, drawing and quartering. But in reality, coin counterfeiters had nothing to fear as it was too difficult to prove what they were doing. Newton therefore set about investigating this phenomenon himself. He had himself appointed justice of the peace, which gave him the power to gather evidence. Between June 1698 and Christmas 1699, he conducted more than 100 cross-examinations of witnesses, informers and suspects. He obtained convictions in 28 cases of coin counterfeiting.

Gold Dominates the English Currency

The Great Recoinage did not see the success the government had hoped for. Therefore, almost two decades after John Locke’s statement, Parliament asked Sir Isaac Newton to write down his views on the correct exchange ratio between silver and gold coins. He wrote an expert opinion, dated 21 September 1717, in which he advised the government to prohibit gold guineas from being exchanged for more than 21 silver shillings. Such an exchange rate was completely outdated and had nothing to do with reality.

Economic historians still argue about whether Isaac Newton was simply mistaken (but how could he be, he was a genius!), or whether he actually had the intention of pushing England towards the gold standard. After all, the law that was passed on his advice resulted in the fact that only gold remained in the country. The English preferred to pay for their purchases abroad in silver, because their silver gave them a currency advantage there. Conversely, those who bought large quantities of goods in Britain paid in gold to get a currency advantage. Soon there were no silver coins left in the country, and the guinea became the most important currency. This effectively set the stage for a monetary system based primarily on gold coins.

No. 2048. George II. Five Guineas 1729. Only 189 specimens known. NGC UNC Details Rev repaired. Estimate: CHF 15,000. Photo: Lübke + Wiedemann KG.

The Crisis of the English Monetary System

Following the death of Sir Isaac Newton, the Royal Mint entered a period of decline. It was no longer profitable to mint silver and bronze, so this area of activity was reduced as much as possible. The production of bronze coinage ceased altogether after 1754.

But the case of gold coins was quite different. It might be that some of the coins were issued privately rather than on behalf of the state, as was the case in many other European mints at the time. After all, state mints struck private precious metal into coins for a premium. This might be the background of the Five Guineas that shows the abbreviation E I C (= East India Company) below the neck of the royal portrait.

No. 2053. George II. Five Guineas 1746. Only 105 specimens known. NGC MS61. Estimate: CHF 30,000. Photo: Lübke + Wiedemann KG.

Given the legend LIMA, the 1746 Five Guineas was probably the result of a similar production process. The English coin dealer Thomas Snelling (1712-1773) claimed that this legend indicated that the coin was made from the gold that George Anson had brought back from his circumnavigation of the globe. Anson captured the Spanish Nuestra Señora de Covadonga, a ship of the Spanish treasure fleet loaded with silver.

Although he lost six of his seven ships and only 500 of the 1,955 sailors survived, the Admiralty considered his voyage a success. After all, he had seized an impressive 34.5 tons of silver.

No mention was made of gold. This has led numismatists to question whether the Five Guineas with the inscription LIMA can really be associated with Anson. After all, it might well be that Thomas Snelling made up this story because Five Guineas with such a nice background sold much better than “ordinary” coins.

No. 2055. George II. Five Guineas 1753. Only 97 specimens known. NGC AU58. Estimate: CHF 20,000. Photo: Lübke + Wiedemann KG

After all, even in the mid-18th century coin collecting was a very popular activity among well-to-do gentlemen. The Five Guineas had become relatively rare in circulation, and these collectors preferred to put them in their collections rather than spend them in everyday life. After all, the value of these coins was too high for everyday use even though the value of the Five Guineas had fallen steadily since its introduction. In 1668, one Five Guineas paid for 71 days’ work by a skilled craftsman. By 1753, it paid for only 52 days’ work. This was also the last year in which the Five Guineas was struck for circulation. At that time, however, nobody knew this.

This becomes clear when we keep in mind that patterns for new Five Guineas were still produced under George III in 1770, 1773 and 1777. None of these were used for the mass production of circulation coins. This was probably because other means of payment were available by then. After all, the Bank of England had been in existence since 1694 and had begun to issue banknotes. Although they did not become legal tender backed by gold until 1833, they were in circulation and readily accepted long before that date.

The era of gold multiples was over, although a few 5-pound issues were still produced in the 19th century. But by then, the guinea was a thing of the past.