Gold!

by courtesy of World Money Fair

Jack London, Klondike and Burning Daylight

One day in December Daylight filled a pan from bed rock on his own claim and carried it into his cabin. Here a fire burned and enabled him to keep water unfrozen in a canvas tank. He squatted over the tank and began to wash. Earth and gravel seemed to fill the pan. As he imparted to it a circular movement, the lighter, coarser particles washed out over the edge. At times he combed the surface with his fingers, raking out handfuls of gravel. The contents of the pan diminished. As it drew near to the bottom, for the purpose of fleeting and tentative examination, he gave the pan a sudden sloshing movement, emptying it of water. And the whole bottom showed as if covered with butter. Thus the yellow gold flashed up as the muddy water was flirted away. It was gold – gold-dust, coarse gold, nuggets, large nuggets. He was all alone. He set the pan down for a moment and thought long thoughts. Then he finished the washing, and weighed the result in his scales. At the rate of sixteen dollars to the ounce, the pan had contained seven hundred and odd dollars. It was beyond anything that even he had dreamed. His fondest anticipation’s had gone no farther than twenty or thirty thousand dollars to a claim; but here were claims worth half a million each at the least, even if they were spotted.

With this discovery, Burning Daylight, central character of Jack London’s novel of the same title, becomes the hero of the prospectors – at least in the novel. The true heroes were others, though.

The discovery

In August 1896, Skookum Jim Mason, an member of the Tagish tribe had come down to the mouth of Klondike river to meet his sister and her husband, a white man by the name of George Carmack. The group came across an odd chap who insulted them: He didn’t want to see any Indians around him here. His tools caught the men’s attention. He seemed to be mining for gold, so Skookum and his companions started to do the same. On August 16, 1896, they struck gold. George Carmack is credited with the discovery of the gold deposits in Rabbit Creek, which later was called Bonanza Creek by the miners. Others claim that Skookum was the one who washed the first nuggets, but being an Indian he was not allowed to register a claim, according to Canadian law. Thus, he left it to his brother-in-law.

The gold rush begins

In July of 1897 the news of gold being found on Klondike spread to the United States that were languishing in an economic depression. Many men, unable to find jobs with the big companies, dreamt of setting out for the wild north to prove themselves as real men, make a fortune and return home. In 1898, forty thousand adventurers were already mining for gold in Canada. They had come from New York, London and Australia, having worked before as teachers or doctors, journalists or accountant clerks. Most of them knew well that they didn’t have much of a chance to find gold, but still they were attracted by the illusion of wealth and adventure. More than half of those who came never took a gold pan in their hands. However, to the scarcely developed northern regions they were a big gain that set off a regular spurt of development.

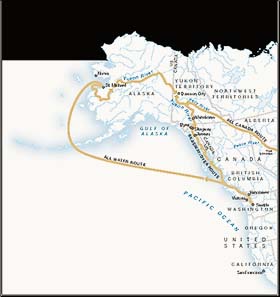

Different routes to the Klondike region

The travel route

Most gold prospectors arrived to the towns of Stagsway or Dyea that were British territory back then. From there, they traveled along the Chilkoot trail to get to Klondike. The Canadian boundary was at the mountain pass of Chilkoot. There, Canadian North West Mounted Police watched over the men who entered the country to make sure each brought sufficient provisions for at least one year, with the intention to prevent food shortages as had occurred in first two years of the gold rush. Besides, the authorities tried to keep out weapons and “criminal elements”. As if it ever were possible to keep such people away from places where gold was found!

At Chilkoot Pass, Canadian police checking the prospectors’ food supplies

Jack London, around 1900

Jack London

Among the adventurers was a young man called Jack London. He had been born in 1876 as an illegitimate child of a spiritually gifted singer and an astrologer. His father, William Chaney, demanded that she had an abortion. Having refused that, his mother, Flora Wellman, tried to kill herself, as Chaney disclaimed paternity. Chaney left Flora and her son. He mother had no choice but to marry the very same year a disabled veteran of the Civil War. Jack London was raised as his son.

Money was scarce in the household, so Jack took his first job at the age of thirteen. Although he worked hard twelve to eighteen hours a day, he wasn’t getting anywhere. Illegal activities seemed to offer a way out. With borrowed money the young rascal bought a sloop and started poaching oyster banks. After his boat got damaged beyond repair, he changed sides and signed up to the California Fish Patrol that was chasing after the oyster pirates, of which he had been one.

Stamina was not his strong point, though. Young Jack quit his job with the police and joined the crew of a schooner, sailed to Japan, came back and took some odds jobs. Then, he fell in with tramps and became a hobo himself, hopping freight trains to travel across the American continent.

After a few years of wild roaming, he returned with his family. He finished school and even was admitted to renowned Berkeley University. But the year 1987 brought many changes. Jack London began to investigate the secret of his birth. Such had been the scandal that the newspapers had covered the story. London found several press articles, coming to know the name of his real father. He tried to get into contact with him, but Chaney didn’t want to have anything to do with him and even pretended he was impotent, only to rid himself of any responsibility. He wrote to Jack, insinuating that Flora had known lots of men then and Jack presumably was the bastard son of one of them.

As we can tell from his reaction, Jack was badly hurt by that letter. He gave up university and joined the gold prospectors.

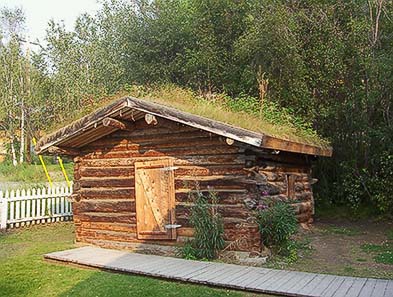

Jack London’s cabin in Dawson in Yukon Territory

On the gold fields

On July 25, 1897, Jack London left for the Yukon. A child of our civilization, though far from pampered, he probably hadn’t the slightest idea of what awaited him in that icy land. While he had to work harder than ever before, he suffered starvation and became sick with scurvy. These experiences left a deep mark on him. Jack London became a socialist and started seeking a way out of capitalism. To escape poverty in the future, he decided to “sell his brains”.

Jack London had already been writing at school, but now he planned to earn a living from his story-telling talent. When he returned home in 1898, he had material for a wealth of short stories and novels. And all the stories he wrote reflect his own desires for freedom, independence, fairness and prosperity, but also the yearning for the warmth of a family and a real home.

Burning Daylight

Burning Daylight, who got his nickname from the other gold diggers because he always is the first to start work in the morning, is one of Jack London’s alter egos. He is just like Jack London would have liked to be: strong, skillful, tough and clever. Thanks to these qualities, he makes his way through the vicissitudes of the gold rush.

His objective is to make a fortune, a real fortune. That’s at least what he says one night at the bar:

“And so I swear once more, by the mill-tails of hell and the head of John the Baptist, I’ll never hit for the Outside till I make my pile. And I tell you all, here and now, it’s got to be an almighty big pile.” – “How much might you call a pile?” Bettles demanded from beneath, his arms clutched lovingly around Daylight’s legs. – “Yes, how much? What do you call a pile?” others cried. – Daylight steadied himself for a moment and debated. “Four or five millions,” he said slowly, and held up his hand for silence as his statement was received with derisive yells. “I’ll be real conservative, and put the bottom notch at a million. And for not an ounce less’n that will I go out of the country.”

A million – that was an incredibly high amount at the end of the 19th century. So, nobody takes him serious. But with relentless energy Daylight continues to look for a chance. And he gets it: Burning Daylight is there the night when Skookum and his brother-in-law show around their find.

After that, in the Sourdough Saloon, that night, they exhibited coarse gold to the sceptical crowd. Men grinned and shook their heads. They had seen the motions of a gold strike gone through before. This was too patently a scheme of Harper’s and Joe Ladue’s, trying to entice prospecting in the vicinity of their town site and trading post. And who was Carmack? A squaw-man. And who ever heard of a squaw-man striking anything? And what was Bonanza Creek? Merely a moose pasture, entering the Klondike just above its mouth, and known to old-timers as Rabbit Creek. Now if Daylight or Bob Henderson had recorded claims and shown coarse gold, they’d known there was something in it. But Carmack, the squaw-man! And Skookum Jim! And Cultus Charlie! No, no; that was asking too much.

Daylight is the only one who believes Carmack and Skookum. He sets out to stake his own claims – and then strikes bonanza for the first time. But instead of going off to the next bar to celebrate his good luck he keeps silence, buying one claim after another until he is the biggest landowner on Klondike River. But he alone can’t cope with the mining work. Thus, the adventurer turns becomes a businessman, sharply calculating but fair. He hires the latecomers, the men who arrived too late to stake claims themselves. As he is offering them good money for good work, he has the best workers.

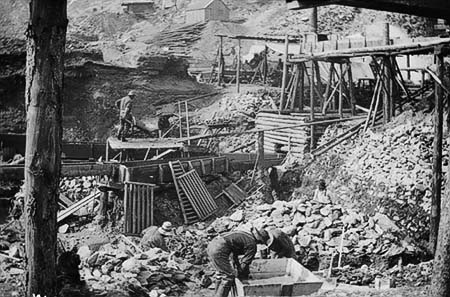

Klondike mining camp, prospectors at work

Other men, themselves failing to stake on lucky creeks, he put to work on his Bonanza claims. And he paid them well – sixteen dollars a day for an eight-hour shift, and he ran three shifts. He had grub to start them on, and when, on the last water, the Bella arrived loaded with provisions, he traded a warehouse site to Jack Kearns for a supply of grub that lasted all his men through the winter of 1896. And that winter, when famine pinched, and flour sold for two dollars a pound, he kept three shifts of men at work on all four of the Bonanza claims. Other mine-owners paid fifteen dollars a day to their men; but he had been the first to put men to work, and from the first he paid them a full ounce a day. One result was that his were picked men, and they more than earned their higher pay.

Even in the middle of success, Daylight doesn’t lose touch with financial reality. Although he is generous – once he sends ten sacks of flour as a present to a dancer, for which she had offered to pay a thousand dollars but not found any sellers –, he cannot understand the prodigality of other prospectors.

Despite the prodigality of his nature, he had poise. He watched the lavish waste of the mushroom millionaires, and failed quite to understand it. According to his nature and outlook, it was all very well to toss an ante away in a night’s frolic. That was what he had done the night of the poker-game in Circle City when he lost fifty thousand – all that he possessed. But he had looked on that fifty thousand as a mere ante. When it came to millions, it was different. Such a fortune was a stake, and was not to be sown on bar-room floors, literally sown, flung broadcast out of the moosehide sacks by drunken millionaires who had lost all sense of proportion. There was McMann, who ran up a single bar-room bill of thirty-eight thousand dollars; and Jimmie the Rough, who spent one hundred thousand a month for four months in riotous living, and then fell down drunk in the snow one March night and was frozen to death; and Swiftwater Bill, who, after spending three valuable claims in an extravagance of debauchery, borrowed three thousand dollars with which to leave the country, and who, out of this sum, because the lady-love that had jilted him liked eggs, cornered the one hundred and ten dozen eggs on the Dawson market, paying twenty-four dollars a dozen for them and promptly feeding them to the wolf-dogs.

Champagne sold at from forty to fifty dollars a quart, and canned oyster stew at fifteen dollars. Daylight indulged in no such luxuries. He did not mind treating a bar-room of men to whiskey at fifty cents a drink, but there was somewhere in his own extravagant nature a sense of fitness and arithmetic that revolted against paying fifteen dollars for the contents of an oyster can.

In the fall of 1897, thousands of adventurers arrive from the Unites States. These men are inexperienced in mining – which shows in their work…

“It – all’s plain gophering”, Daylight muttered aloud.

He looked at the naked hills and realized the enormous wastage of wood that had taken place. Each worked for himself, and the result was chaos. In this richest of diggings it cost out by their feverish, unthinking methods another dollar was left hopelessly in the earth. Given another year, and most of the claims would be worked out, and the sum of the gold taken out would no more than equal what was left behind.

Daylight sends for engineers from the United States to organize the mining according to modern technical standards. At the same time, he begins to improve the infrastructure of the country, building water pipes and power plants. At some point, he becomes aware that the gold rush has passed its peak. Before others start to notice, he sells his properties – with a gigantic profit margin.

But having done the thing, he was ready to depart. And when he let the word go out, the Guggenhammers vied with the English concerns and with a new French company in bidding for Ophir and all its plant. The Guggenhammers bid highest, and the price they paid netted Daylight a clean million. It was current rumor that he was worth anywhere from twenty to thirty millions. But he alone knew just how he stood, and that, with his last claim sold and the table swept clean of his winnings, he had ridden his hunch to the tune of just a trifle over eleven millions.

Eleven million dollars – an incredible amount, in those days! Daylight takes the money with him to the East coast and undergoes a transformation – having been a fair player before, he now turns into the epitome of a ruthless capitalist. But all his interest rates and rates of return don’t make him happy. In the story, a woman holds up the mirror to him:

“Now we come to you. You don’t create anything. Nothing new exists when you’re done with your business. Just like the coal. You didn’t dig it. You didn’t haul it to market. You didn’t deliver it. Don’t you see? That’s what I meant by planting the trees and building the houses. You haven’t planted one tree nor built a single house.”

Naturally, Daylight is willing to be won over (after all, the novel is also a love story). He burns the bridges to the world of finance, marries the energetic lady and buys a ranch to stay there with his beloved and earn a living by farming.

But then, something outrageous happens. One day, as he is inspecting the site of landslide, he discovers that his ranch stands on a huge gold deposit. Instantly, he is seized by the old greed again and starts digging, busy with estimates, plans and calculation – and he’s shocked! The day has gone by without him noticing. Slowly he rides back home. His wife greets him fondly, caressing his hair, and suddenly Daylight becomes aware of what is really important to him. It’s not the gold – he doesn’t want to lay eyes on it again.

“But I’d sure like to see any blamed old slide get the best of me, that’s all. I’m going to seal that slide down so that it’ll stay there for a million years. And when the last trump sounds, and Sonoma Mountain and all the other mountains pass into nothingness, that old slide will be still a-standing there, held up by the roots.”

Daylight plants eucalyptus trees to secure the slide, so that nobody shall ever know of the biggest gold strike since Klondike.

And they lived happily ever after – that’s how one would like this story to end, but reality caught up with the inventor of the story.

Jack London on his ranch, photograph from 1914

The writer’s ranch

Because it had been Jack London’s own dream to become a farmer and cultivate the land, together with a woman. In 1905, he purchased a 1,000-acre ranch (about 4 km²) at the foot of the Sonoma Mountains in California for the price of 26,450 dollars.

This enterprise was a complete flop. Some biographers claim that he just was unlucky or that his approach to farming was ahead of his time, others say the disaster was due to mismanagement and bad leadership. In any case, the writer had to produce more and more books at an ever-increasing pace, to make up for the farmer’s losses.

Jack London died on November 22, 1916, most likely due to renal failure. Decades of drinking and massive morphine abuse had badly affected his health. He left countless stories, which do not only appeal to the imagination of teenagers. When we pay attention to what he is saying between the lines, we understand the desires, ambitions and hopes, and also the doubts and fears of a whole generation, which, shaken the impact of short-lived success and big crises, prepared the ground for our modern capitalist society.

By the time of Jack London’s death, the big Yukon gold rush had long ago subsided. But gold mining was never given up there. In the meantime, the amount of extracted gold is said to be around 12.5 million ounces, which equals a cube of an edge length of a good 20 meters.