Charlemagne and the Popes – On the way to the Imperial crown

Pepin the Short and Zachary – or – The Carolingians assume the title of king

In 768 Pepin the Short died. He was the Frankish Mayor of the Palace who had deposed officially the Merovingian mock kings.

Pepin the Short, 752-768. Denarius, Angers. Depeyrot 40. From auction Künker 205 no. 1394. Estimate: 5,000 euros.

His collaboration with Pope Zachary had enabled him to send Childerich III and his son Theoderich to a monastery and assume for the Carolingians the title of King.

Charles and Adrian I – or – The End of the Langobardic Kingdom

Pepin had prearranged the time after his death. According to Frankish law he divided his empire between his sons Charles and Carloman who, however, soon began to quarrel over daily matters. Then, suddenly the younger Carloman died aged only 20. He left behind two sons who, though, were too young to assume power.

Anonymous Lombardic issue from Pavia. Tremissis in the name of Mauricius Tiberius, seventh cent. Arslan 11var. Künker sale 205 (March 12 and 13, 2012), 1259. Estimate: 1,000 euros. The deformed inscription dates this coin after the first quarter of the seventh cent.

Therefore their mother fled with them to her father, Desiderius King of the Langobards. Naturally he did not wish his Frankish neighbours to reunite again under one single ruler. Thus Desiderius supported his grandchildren’s claims.

There was one option for making them king beyond argument: The Pope had to anoint them. But Adrian refused to cooperate. To Desiderius this offered good reason to raid his neighbour’s territories. And Pope Adrian acted according to the old saying: My enemy’s enemy is my friend. He sent messengers to Charles who of course did not miss this chance.

In the summer of 773 Charles gathered his army not far away from Geneva. In two divisions they marched to Italy. Hence they managed to attack the Langobardic army from behind while the Langobards had tried to block the enemy’s way. Desiderius seeked shelter in Pavia, a very strongly defended city, nearly impregnable with the instruments of that time. Thus Charles had no alternative but to starve out the inhabitants. It took nine months to do so. In the meantime Charles went on to Rom, renewed the alliance with the papacy, and returned to the north just in time to accept the capitulation on 4 June 774. This was the end of the Langobardic empire.

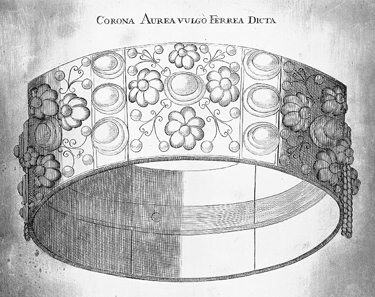

The Langobardic crown. Copper plate engraving by Nicolaus Seelaender (1716). Source: Wikipedia.

Charles took the title “King of the Langobards” and banished Desiderius to a Frankish monastery. To build up a broad power basis for Charles’ second campaign into the south he appointed to masters of the new territories Frankish, Alemannic and Burgundian noblemen.

By the way, this campaign constituted an enormous change to the papacy: The Pope won great territories in central Italy. And to show clearly the realignment of policy henceforth all Papal documents were no longer dated following the Eastern Roman emperor but according to the rule of the new patron, the Frankish king Charles.

Charles and Leo III – or – Christmas, 800

On 25 April 799 a group of Roman noblemen assaulted Pope Leo III. If we follow the narration of the Liber pontificalis the assaulters dragged him to the ground, put out his eyes and cut out his tongue keeping him prisoner in a monastery later on. But there Leo III recovered miraculously; he was able to escape with assistance of his chamberlain Albinus climbing over a wall with a rope. Actually, these records cannot claim complete historicity. There are indications that opponents to Leo III instituted impeachment proceedings against him because of adultery and perjury deposing him in the end.

Anyway, Leo saw no other ally than Charles. The Frankish ruler was the only one who commanded sufficient power to put down the rebellion against Leo. So there was nothing else for it but to go to the Franks.

Charlemagne, 768-814. Denarius, Tours (Saint Martin). Depeyrot – (cf. 1051). Künker sale 205 (March 12 and 13, 2012), 1402. The abbey of St Martin in Tours was headed by Alcuin, one of the most prominent collaborators of Charlemagne. Thanks to his letters we know some details about the background of the “Leo III affair”.

From letters of Alcuin, one of Charles’ leading collaborators, we know that Leo was not accommodated in the Frankish empire without critics. Leo’s enemies had raised allegations against him even before his arrival; not even a Pope’s friend like Alcuin tried to deny their validity. Instead he argued that the successor of Saint Peter was invulnerable and for this reason Charles being King of the Franks had to secure his immunity, especially because the office of (Eastern Roman) emperor was vacant. To be precise this was not correct. In Constantinople Empress Irene was acting ruler. But, anyway, a Frankish nobleman could not imagine a woman to be ruler.

The solemn receiving of the Pope in Paderborn showed distinctly to everybody that Charles had decided in favour of Leo III. Later Charles sent him back to Rome with a military escort; there the riot had collapsed, yet – the sources are not clear about whether Frankish troops had played a role in this affair or not.

On 24 November 800, quite exactly one year after these events, Charles made his entrance in Rome. The accusations against Leo had not been disposed of once and for all. Thus Charles convened a synod with the only goal to settle the charges against Leo. But this did not work out. After three weeks of debates, there remained but one last way: an oath of purgation. Thus Leo swore on 23 December: “I have no knowledge of the false accusations which these Romans have charged me with wrongfully, and I know that I have never done such.”

Coronation of Charlemagne, pictured in the Vatican “Stanze” by Raphael. Source: Wikipedia.

Why Leo was not put to trial? We simply do not know. Neither do we know what the negotiations between Charles and Leo were about. However, on Christmas the Pope crowned Charles Roman Emperor – to assure as many spectators as possible assisting to that incredible event. Maybe he did so out of thankfulness, but maybe they had settled in advance for that price Leo had to pay for his acquittal.

Portrait denarius of Charlemagne – evidence of his coronation in 800

On 12 and 13 March 2012 in its auction 205 auction house Künker puts to sale an extremely rare Carolingian denarius featuring the portrait of Charlemagne. The rare piece is the highlight of a vast collection of medieval coins including large series of Langobardic and Carolingian issues. There are less than 35 specimens of our portrait denarius in the whole world.

Charlemagne (800-814). Portrait denarius. Denarius, unknown mint. KARLVS IMP AVC Bust to right with laurel wreath and allocated cloak. Rv. XPICTIANA RELICIO church building. Depeyrot 1166. Künker sale 205 (March 12 and 13, 2012), 1405. Estimate: 30,000 euros.

The obverse shows the bust of Charlemagne to right. He wears the laurel wreath typical of the Roman emperors and the paludamentum, a rider’s cloak, symbol of the Roman commanders. The inscription – KARLVS IMP(erator) AVG(ustus) – and the image clearly refer to ancient models. But nevertheless the denarius is much more than a simple imitation. Because the reverse alludes to the new reality: We read the inscription XPICTIANA RELICIO (Christian faith) arranged around a church.

Since decades specialists are discussing when exactly these coins, which are quite uncommon of the middle ages, were made. The obvious date would be – as indeed older studies had proposed – immediately after Charles’ coronation as emperor.

But more recent analyses challenge this dating. Nowadays we dispose of a relative chronology of Charles’ various issues. In the line of this chronology the portrait denarii are put right in the end, and it is absolutely unimaginable that only so few coins have survived from the years between 800 and 814.

There are two ways to explain their scarce number. They could have been part of a celebration issue in occasion of Charles’ coronation. Another possibility suggests the moment when the Eastern Roman Emperor acknowledged Charles in 812. However, this would mean that Charles had demonstrated his empire to depend on the acknowledgment by Byzantium. Considering Charles’ policy on the whole this seems very unlikely.

Anyway, even if the dating is not fixed in detail, these uncommon issues are very fascinating. At 30,000 euros Künker has estimated this key piece of Carolingian numismatic that reminds us of one of the great moments of occidental history.

You will find a comprehensive preview of the whole auction here.