The People of Zurich and their Money 9: Burning a woman – 7 pfund 10 shilling

by courtesy of MoneyMuseum

Our series ‘The People of Zurich and their Money’ takes you along for the ride as we explore the Zurich of times past. Today, you will learn from Master Hans which price he charged the Säckelmeister (treasurer) in 1701 – for torturing, beheading and burning a human being! Much like a good DVD, this conversation comes with a sort of ‘making of’ – a little numismatic-historical backdrop to underscore and illustrate this conversation.

December 1701. Hans Jakob IV. Volmar, executioner and knacker of Zurich, presents his semi-annual invoice to the treasurer. Drawn by Dani Pelagatti / Atelier bunterhund. Copyright MoneyMuseum Zurich.

Treasurer: Ah, master Hans, you’re bringing your invoice?

Volmar: Yes, treasurer. This time it’s more than usual.

No wonder, the affair of the witches from Wasterkingen cost us dearly. This was a good deal for you.

Indeed, just think of the first execution. Burning Elisabetha Rutschmannin alive to dust and ash: 7 pounds 10 shillings, cutting off the head of her daughter Anna Wiserin and burning her body at the stake to dust and ash: 3 pounds 10 shillings, likewise Margaretha Rutschmannin: 3 pounds 10 shillings. The evening snack for the city guards: 3 pounds 4 shillings.

I get scared.

This runs up to 17 pounds 14 shillings.

And the cost of the torture!

One pound for the first visit in order to frighten the delinquent, three pounds for the shearing, 3 pounds for the torture.

This can’t be true, three pounds for cutting the wenches’ hair?! That’s a lot of money!

Don’t forget, that the evil powers of witches are often hidden within their hair. This belongs to my most dangerous tasks.

Hence, 21 pounds for three full torture procedures.

No, 27 pounds. Elisabetha Rutschmannin revoked twice. I had to torture her three times.

I see, and here you’ve invoiced the costs of the liniment you’ve used to treat her after the torture.

Yes, 18 shillings, but after my treatment she was able to walk herself to the place of execution, although she was 70 years old and went through three tortures!

I see, this was a losing business for the treasury. The confiscated estate of the three witches fetched only 582 gulden. The houses were sold under their real value. Nobody wanted to buy a house where a witch had lived.

582 gulden. My invoice adds up to 25 gulden! And where’s the rest of the money?!

We had to pay compensation for the investigating judges. The supreme judicial authorities got their money. And of course we’ve got to invoice the costs of the prisoners’ guarding and maintenance. And don’t forget the indemnities and travel expenses of the witnesses. They all had to come from Wasterkingen. The public treasury will have to pay the balance!

But this is only because the aldermen pick up the largest part! So stop complaining and pay my invoice. I haven’t asked for more than what I’m owed.

Executioner in the course of preparation. Praxis rerum criminalium iconibus illustrata, Antwerp 1562. Source: Wikipedia.

Making of:

‘I haven’t asked for more than what I’m owed’, these words conclude the audio drama involving the executioner Hans Jakob Volmar, who presented the Säckelmeister of Zurich his invoice for the second half of the year 1701. As a matter of fact, we know exactly what the Council of Zurich deemed right and fair in regard to the payment of the executioner. There is a document extant, a kind of rate, which lays down the wage of any of the headsman’s services. It specifies in a quite down-to-earth and technical way the different kinds of execution methods according to their effort as well as the ‘minor’ tasks. In addition to the payment for torture and execution, the executioner of the city of Zurich received an annual salary in coins and kin for the sole reason that he lived in Zurich permanently and hence was at the Council’s disposal at all times.

Even though the payment was excellent – and, on a single judging day, an executioner might well earn wages many times higher than the salary of a workman –, it would not have sufficed to assure his livelihood. Hence, he was appointed some additional jobs, too. The range of duty as Wasenmeister or renderer, as we would put it today, included the disposal of carcasses and the cleaning of sewers.

Apart from his main job and the revenues from the treasure, every headsman operated another business – Hans Jakob Volmar was no exception, he worked as a doctor. He made substantial profits by that, not only thanks to his possession of mysterious substances such as human blood and human grease as well as mandrakes. He gained considerable knowledge of the human body thanks to his using torture and treating the wounds and dislocations inflicted by his measures. Thus, Master Volmar’s demand for 18 shilling for an ointment he used to treat one of the witches has a real historical backdrop.

Besides, Master Volmar as well as the Witches of Wasterkingen are historical figures. Hans Jakob Volmar belonged to an old family of headsmen who held this office for generations in Zurich and Schaffhausen. The first one, Master Paulus, had assumed office in Zurich in 1587. He was succeeded by his two sons, Hans Jakob Volmar, working as executioner and Wasenmeister in Zurich between 1697 and 1711, was his great-great-grandson. Just like most of his relatives, Volmar worked as practicus medicinae, hence medical practioner, after he had retired.

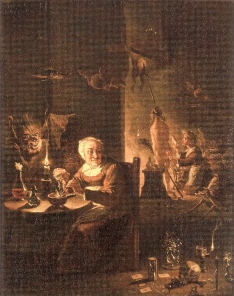

Witch scene, group of David Teniers the Younger (1610-1690) around 1700. Berlin, German Historical Museum. Source: Wikipedia.

Elisabeth Wysser-Rutschmann, out of whose death Master Volmar earned 7 pfund 10 shilling, was convicted of witchcraft and consequently executed on July 9, 1701, together with her daughter Anna Rutschmann, referred to as Anna Wiserin in the verdict, and her sister Margaretha Rutschmann. In April 1701, these three women had been accused by their neighbors in Wasterkingen of doing harm to the local human beings and animals alike by using magical powers. The three defendants were brought to Zurich on April 28, accompanied by an exhaustive list of allegations. Enfeebled by Master Volmar’s torture, 24 year-old Anna was the first to plead guilty; she confessed herself of witchcraft, having been introduced to the art of witchcraft by her mother and her two aunts as well as a woman called Anna Vogel. After having undergone heavy torture, Elisabeth and Margaretha Rutschmann likewise plead themselves guilty. They were sentenced to death by burning; Elisabeth’s verdict involved the most severe penalty: she was burned alive whereas Anna and Margaretha Rutschmann were beheaded before burning. That year, another three women and a man from Wasterkingen died as convicted witches or wizard, respectively, on Zurich’s place of execution.

After their deaths, churchwarden Anton Klinger considered himself to be haunted by the devil. The man wasn’t impressed by any form of enlightenment and stubbornly claimed that the devil was lurking about in his house to avenge him for his drastic measures against the witches of Wasterkingen. His friends advised him to check his menial staff and, as a matter of fact, it turned out that he had been fooled by his assistant: because the latter wanted to pursue his amours without being interrupted, he had acted as ‘devil’. Details of this hoax were unveiled in a trial. The entire city laughed about the haunted churchwarden and, all of a sudden, regarded the accusation of witchcraft ridiculous in general. The Wasterkingen witches were the last ones that were burnt in Zurich.

The upcoming episode has a programmatic title: ‘The troublemaker’, i.e. Johann Heinrich Waser, one of Zurich’s most important citizens of the 18th century – and one of his most controversial.

You can find all other parts of the series here.

The texts and graphics come from the brochure of the exhibition of the same name in the MoneyMuseum, Zurich. Excerpts with sound are available as video here.