The Design of the Circulation Euro Coins: Austria – 2 Euros – Bertha von Suttner

translated by honeycutshome

The euro coins are a splendid means for all countries in the eurozone to convey their own self-conception. Bertha von Suttner was at the forefront of a peace movement that considered in the early 20th century that all future wars could be prevented. Thus, she is a worthy protagonist for the Austrian euro coins.

Austria has chosen its designs from three fields in equal shares: art, nature and the persons that have shaped Austria. Bertha von Suttner represents the women of Austria. She is the only real member of the female sex that has made its way onto one of the euro coins as national subject. But who was this woman who was the first female Nobel Peace Prize winner in 1905?

Bertha von Suttner, 1906. Photograph by Carl Pietzner. Source: Wikicommons.

Bertha Sophia Felicita Gräfin Kinsky von Chinic und Tettnau, later to be known as Bertha von Suttner, had been born at Kinsky Palace in Prague on 9 June 1843. On her father’s side, she belonged to one of the most famous families of Bohemia. Her mother, however, wasn’t considered of equal status; and when her father died before she was even born, the surviving widow and the semi-orphan could only expect beneficent gifts from his family.

A friend accommodated. Landgraf Friedrich Fürstenberg financed Bertha von Suttner’s childhood in Brünn. As was customary for aristocratic children back then, she, too, grew up under the watchful eyes of English and French governesses. It was during these years that she received her top-class education that was to serve as basis for her socializing on an equal footing with the most influential people of the world.

If you had met little Bertha at the age of 13, you wouldn’t have noticed any difference to other noble young ladies. The only thing she worried about was what to wear for the next dinner, the next tea dance, the next picnic. But her mother gambled away the small inheritance from her husband in the casino at Wiesbaden and so forfeited the benevolence of her host. Mother and daughter had to move to Vienna where they were on short commons.

For the situation to take a turn for the better there was basically only one option available in those days: Bertha had to marry well. She was pretty and flirtatious, so why not? Hence, it didn’t take long for the first suitors to arrive. But there was no such thing as Prince Charming – the suitors were established gentlemen advanced in age that surely would have provided a secure home for Bertha and her mother. Bertha, on the other hand, didn’t want to spend the rest of her life with one of these elderly guys, and her career as an opera singer didn’t get momentum either.

Arthur Gundaccar von Suttner. Source: Wikicommons.

So, Bertha had to decide on what she wanted to do: continue living with her mother in narrow circumstances or getting herself a position? Bertha went for the latter. What options did a young educated lady have back then, a lady with perfect skills in three foreign languages? Well, not many, she could either become a governess or a lady’s companion. Bertha became governess in the house of Baron Carl von Suttner. The girls in her charge cherished her and saw a friend and an ally in her. Likewise Arthur von Suttner, the brother of her charges, showed up conspicuously often in the schoolroom of his sisters. He had fallen in love with light-hearted Bertha. The happiness lasted for two years before the mother found out and gave Bertha the choice whether to quit or be sacked. Bertha complied, accepted a position as secretary at the intercession of the baroness and went to Paris to meet her new employer.

Alfred Nobel. Painting by Emil Östermann. Source: Wikicommons.

That trip was to influence Berth’s life considerably. She had become the employee of no less a figure than Alfred Nobel, inventor of dynamite and later to institute the Nobel Peace Prize, who was incredibly rich already at that time. Nobel was a cynic, a misanthropist who nevertheless always looked for the good in people. Bertha, in turn, was spirited, vital and brimful of life; in short she thrilled everyone near her. Nobel fell in love with her immediately. He would have loved nothing better than to marry her right away but Bertha still loved Arthur von Suttner who had realized in her absence that he couldn’t and didn’t want to go on living without his Bertha. That he told her by telegram and so Bertha left promising Nobel to return to von Suttner at once.

Suttner’s living house in Usnadzis qucha in Tbilisi (Georgia). Photograph: Traubenberger / Wikicommons.

They married against the wishes of Arthur’s parents on the quiet and went on board a ship for Georgia. Bertha had become acquainted to the princess of that little country once, and hoped for her protection. But she misjudged the situation. The two of them had to manage on their own. It was something of an obstacle that neither Arthur nor Bertha was ever to master the Georgian language which of course diminished the chances of earning a living significantly. That was why Bertha started to write froth serial novels for journals like ‘Die Gartenlaube’. In addition, she read everything she could get her hands on. That was her link to civilization, her way of escaping Caucasian poverty. When Bertha returned to Austria in 1885, she was 42 years old and hadn’t shown any interest in politics so far. She considered herself an influential writer and intended to write a novel that was to stir up mankind. Her treatise ‘Maschinenzeitalter – eine Zukunftsvorlesung über unsere Zeit‘ (English: ‘The Machine Age‘) was published in 1888. It was a flop. But Bertha wasn’t discouraged by that. She began doing research for another book, a novel of purpose that took the fate of an individual to name and shame the barbarity of a system. The peace movement was rather active in Europe at that time, and so Bertha deemed this an appropriate topic. Under the title ‘Die Waffen nieder’ (English: ‘Lay Down Your Arms’), she wrote a fictional autobiography of a noble lady who loses her husband in 1819 near Solferino, and due to other acts of war faces the danger of losing her second husband who is eventually shot dead in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870.

It is thanks to this novel that Bertha von Suttner became a peace activist. The research for her book had horrified her: “…In order to make the added historical events match reality, to make the description of the battle scenes come alive I had to pursue studies first, gather material and documents. … I read in huge tomes about history, delved among newspapers and archives to find records of war correspondents and military surgeons; I listened to battle stories told by those acquaintances of mine who used to be in the war and during that time my abhorrence for war increased until it reached a painful intensity. I can assure that the pains I made my female protagonist endure likewise afflicted me during my work.”

‘Die Waffen nieder’ made Bertha von Suttner known in the entire civilized world all at once. She became a symbol of the peace movement. And Bertha soon became accustomed to her new role. From then on, writing took a back seat for it was more important to organize the peace movement and get it a better hearing from the public. That wasn’t an easy thing to do in an era when nationalism and militarism were the only trends the government approved of!

The main problem for Bertha was that the sole income for her family was generated by her activities as a writer. In order to meet her obligations as champion for peace, however, she had to neglect her writing. Instead, she attended peace conferences, socialized with noble families in order to get the powerful interested in the ideas of peace. In this regard, old-fashioned clothing would have had counter-productive effects, at least in Bertha’s view, since that would have damaged the prestige of the peace movement. The result of that thinking was that the family lived in constant feat of the distress warrant. Strictly speaking, the activities of Bertha’s were only made possible with the aid of an old friend, i.e. the one Bertha had dumped in Paris 20 years ago.

Memorial plaque for Bertha von Sutter at Kinsky Palace, Prague. Photograph: R. Kukacka/L. Jerábek / Wikicommons.

Alfred Nobel had followed with interest what his former love was doing. He had read the novel ‘Die Waffen nieder’ and made some really positive remarks about it. After all, he considered himself a protagonist of peace as well. That may sound somewhat peculiar for a man who earned his living mainly with the production of explosives. But Nobel held the view – as did many of his contemporaries – that the modern weapons would render war per se impossible. What was the point of prevailing when all you get was a devastated country? He deemed his dynamite another way to achieve peace because surely nobody of sound mind would be willing to use such horrible a weapon.

Thanks to his enormous wealth, he was able to send Bertha money more than once that she could spend on traveling and the projects of the peace movement. But that was like a drop in the bucket. Bertha needed more money, and so she tried to convince Nobel to bequeath a part of his fortune to the peace movement – and she drew no significant distinction between the organization and herself as a person. The outcome was a will with which Alfred Nobel bequeathed 35 million SEK the interest on which was to finance a prize for those with outstanding contribution for the benefit of mankind, in physics, chemistry, medicine, literature to be specific, and “to the person (à celui ou celle) who shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses.” The exact wording “à celui ou celle” is interesting here; at the end of the 19th century, it wasn’t common procedure to include women in the circle of potential prize winners. Bertha von Suttner thought that it applied specifically to her. After the testament became known she wrote to a friend: “The Nobel fund? Yes, I find it great, magnificent and I am all the more proud since it was I who had introduced Nobel to this movement and suggested to him to do something of importance for it. I am steeped in the awareness that I, being the moral initiator of this 7 million-contribution and this spectacular promotion of the idea of peace, am entitled to claim the first disbursement – not to mention the fact that my catch phrase has a lasting effect and that I know that in my hands this money will come to fruition again in the interest of peace.” Bertha was furious and indignant that she had to wait four years until the Norwegian Parliament finally awarded her the Nobel Peace Prize in 1905. She would have needed the money so badly! The financial burden had become heavier and heavier, Arthur had died in 1902 and the castle of the von Suttner family had to be sold. Bertha alone carried the entire financial burden. Thus, the money that came with the prize wasn’t so much used to finance the peace activities but the life of Bertha’s relatives.

Bertha von Suttner worked for the promotion of peace for a quarter of a century. She gave lectures, wrote articles for newspapers and tried to convince the most influential figures of the day in one-to-one talks. She was a great fighter against anti-Semitism, which was rampant at Vienna at that time, and supported the movement propagating the foundation of a European Parliament. She considered herself a cosmopolitan and adhered to the faith – even though she renounced God and the church – that mankind would change for the better. She was convinced that it would be just a matter of time before all national sensitivities were abolished and the wars banished from the world.

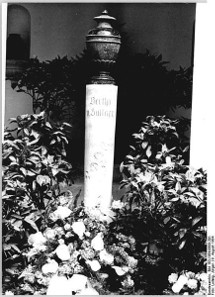

The urn of Bertha von Suttner in the columbarium of the main cemetery at Gotha. Photograph: Jürgen Ludwig / Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-1984-0809-301 / CC-BY-SA / http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en

Wearied but happy, Bertha von Suttner died on 21 June 1914. Only a couple of days before, she had written a friend who had urged her to consult other doctors about her gastric trouble: “But why? I have lived long enough, I have achieved something in my life, and my time has come, so be it. I don’t cling to life.”

Perhaps Bertha von Suttner was well aware as to why she didn’t want to continue living. After all, her death saved her from admitting that the peace movement hadn’t managed to win approval with the broader masses. Only very few people really wanted to prevent the great world war from happening that was to begin only seven days after she died, when the Austrian heir to the throne was assassinated in Sarajevo.

The depiction of this colorful figure on the highest denomination of the 2 euro coin reminds us that joint interest and economic unification apparently are a better means to unite Europe than the efforts of all idealists of the world put together.

Visit the Bertha von Suttner Project to access images, texts by and about Bertha and more.

Or take a look at the short documentary “Bertha von Suttner: The Woman Behind the Peace Prize”.