The Design of the Circulation Euro Coins: Spain – 1 Cent – 10, 20 and 50 Cent – Miguel de Cervantes

By

The euro coins are a splendid means for all countries in the eurozone to convey their own self-conception, addressing their own citizens who use the small change on a daily basis, addressing all European citizens to whom the coins find their way…

So, how do the individual countries represent themselves? What do they deem important enough to be praised on their coins and for what reason? What do the different designs of the euro coins mean in the state where they have been minted? And why did they find their way into the national coinage?

It is Spain’s golden age the 10, 20 and 50 cent pieces of the country allude to. The same era, however, is connected with inquisition, exploration of the Indians and bloody religious wars in which kings like Philipp II drove the state to become bankrupt in order to press the Netherlanders into Catholicism again. Strictly speaking, the golden era is not really appropriate to advertise the country. But wait, this period also has a charming representative, Miguel de Cervantes, writer of Don Quixote. Choosing him as depiction of a coin is a masterstroke allowing the former global power Spain to give the best account of itself.

Portrait of Miguel de Cervantes y Saavedra (1547-1615). Source: Wikicommons.

It is hard to decide which is more thrilling: the adventures of Don Quixote or the vita of its creator, Miguel de Cervantes. The writer’s biography sounds like an adventure movie conceived by the best of scriptwriters.

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra was born on 29 September 1547, into a family of hidalgos, members of the non-titled nobility. In the 16th century, many Spanish people proudly insisted upon belonging to the nobility. Most of them, however, didn’t possess anything, apart from an iron sense of honor. The father of little Miguel formed no exception from the rule.

He sent his son to Madrid, to attend upper secondary school. There, the teachers became aware of his literary talents and he was given the opportunity to work for the royal court. But before Cervantes could take advantage of that opportunity, he had to flee from Spain. He had seriously wounded a man during a fight. We don’t know what the reason for this fight was. The case records merely state that Cervantes was found guilty and that he was to have his right hand cut off in public. But when the warrant was served on 15 September 1568, Cervantes was already on his way to Italy where he then assumed the office as papal legate.

The Battle of Lepanto 1571. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Caird Fund. Source: Wikicommons.

The young man didn’t remain in this peaceful business for long, though. As early as the following July we find his name on the payroll of Spanish regiments in Naples. There the Spanish ruled, too, and they were making the preparations for the big naval battle that was to go down in history as the victory at the Battle of Lepanto. And Cervantes was one of a party. On 7 October 1571, a Christian army commanded by Don Juan de Austria defeated the Turks. But Cervantes nearly missed everything because he had to stay below deck!

The court records registered that in an inquiry a witness, a comrade-in-arms, replied that “he knows and saw that when the Turkish fleet was recognized by our Spanish fleet, said Miguel de Cervantes was sick with a fever, and this witness saw that his captain and other friends told him that since he was sick, he could not fight, but, rather, he should go below deck of said galley because he was not in condition to fight. And then this witness saw that said Miguel de Cervantes responded angrily to said captain and to the others who had said this to him: ‘…I have been ordered and have served very well as a good soldier and so now I will do no less, although I be sick and with a fever. It is better to fight in the service of God and of His Majesty and die for them than to go below deck.”

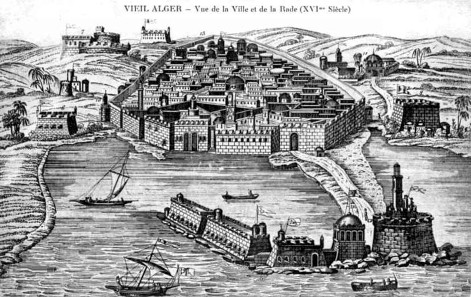

The cashbah of Algier in the 16th century. Source: Bachounda1 / http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

Cervantes didn’t die, but he was shot in the chest twice and lost his left hand. He spent months in a hospital in Messina before he could return to duty. On 7 September 1575, he took passage to a ship in Naples that was heading for Spain. In his pocket he kept a letter of recommendation addressed to Philipp II, King of Spain, signed by no less a figure than Don Juan de Austria. But Cervantes wasn’t lucky. His ship was hijacked by pirates, and he was kidnapped and brought to Algiers. Back in the 16th century, Algiers was not just a major base for the pirates, but it also had an important slave market. Cervantes wasn’t sold, though. His letter of recommendation made his owners hope for a high amount of ransom money. He was treated with great respect. Cervantes was allowed to move about freely in the city. Several times, he tried to escape.

The first attempt failed before it was even put into action. A middleman gave Cervantes away. The second time Cervantes and his 15 fellow captives got free for a short period of time until they were recaptured by the pirates. They had to face gruesome punishments. One slave was hanged upside down until he died of pulmonary hemorrhage. Cervantes was lucky. He was sentenced to ‘just’ five months of incarceration. When Cervantes tried to escape the third time, the messenger was caught and executed afterwards in a horrible way: a stake was driven into him but with enough care to prevent any damage to vital organs. It took days for the poor devil to die. Cervantes was sentenced to 2,000 hits with the club. But the pirates spared Cervantes even this penalty. Instead, they brought him to a dungeon in the palace. Upon release, Cervantes organized a mass jailbreak that was given away by a black friar. Then, the pirates were finally fed up with him. The fearless prisoner was to be chained to the rudder of a galley ‘with two chains and bilboes’. Virtually in the very last second, a member of the Trinitarian Order managed to come up with the ransom money to redeem Cervantes.

Statue of Cervantes in present-day Naupactus, ancient Lepanto, in Greece. Photograph: vlahos vaggelis / http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en.

Happy about the regained freedom, Miguel de Cervantes set out for Spain. The former participant in the Battle of Lepanto and hero of Algiers intended to start a new life there. However, he wasn’t the only one who tried to realize that plan. In those days, Spain was full of invalids who claimed to have fought at Lepanto and to have been held captive at Algiers. Cervantes had never learnt to boast or to bow and scrape, and so it was bound to happen: Cervantes remained unemployed. He made good use of the time and started to write. Some books were produced which admittedly are of interest only to modern philologists.

Cervantes had his difficulties adjusting to every-day life. After his return, it took him seven years to get himself a permanent job. He was appointed royal requisitioner of grain and oil, meaning that he travelled through all of Andalusia on behalf of the king, to purchase foodstuffs. But the farmers didn’t like to sell their goods to the king who paid only a fraction of what their products were worth. A wholesale buyer of the state had to apply pressure, and so Cervantes did, but more on the rich than on the poor. Consequently, he was excommunicated by the canons of Seville because he had confiscated grain from their estates. Even though the clerics had to go back from that decision, Cervantes surely didn’t make any friends that way.

His fate was sealed by the bankruptcy of another man. Cervantes had entrusted royal money to a banker who embezzled it. The state held Cervantes responsible. He was obliged to pay the money back. That, however, he couldn’t and so Cervantes spent seven months in prison which was a bitter experience for such proud a man. On the other hand, we mustn’t feel too sorry for the poor prisoner since, being incarcerated, Cervantes found time to start with his Don Quixote, the book that was to bring him fame still in life and, most of all, money.

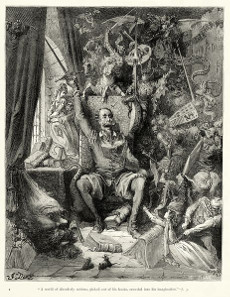

Illustration of Don Quixote by Gustave Doré (1832-1883). Source: Wikicommons.

The basic idea of Don Quixote is a simple one: Cervantes wanted to caricature the chivalric novel so popular in Spain in that era. There, heroes were at the focus of attention that had met their Waterloo, just like Cervantes had done. Thus, he creates his Don Quixote, a man who went insane because he took the chivalric novel literally. But what does insane mean? Don Quixote simply became incapable for every-day life since he took a shaving bowl for the legendary helmet of giant Mambrinus and windmills for giants. The book about the Knight of the Sad Countenance became a bestseller when its author was still alive. It is published in more than 2,000 editions, in more than 50 languages. Cervantes’ contemporaries had the time of their life when reading Don Quixote. They loved the adventures of the crazy knight. Soon, every skinny horse was called Rosinante, and in the carnival parades Don Quixote and his characters became the most popular subject.

So, it is a 16th century-bestseller? It is just a hilarious story? Well, the novel is about much more: it shows the Spanish society exactly the way it was back then, covering the noble hidalgo as well as the humble cook-maid. Cervantes paints his images with sympathy, but also with great observation skills and a critical pen. He did so in the best New Castilian, the language that was to become the Spanish standard language. And his novel invited any era to interpret it in its own way. Goethe had read it (“Cervantes keeps me at the records like a vest made of cork buoys up the swimmer”), Heine (“I vividly remember the time when I stole away from the house in the very early morning and hurried to the court garden in order to read my Don Quixote without any interruption”), Rilke (“…I rather find it infantile”) and Dostoyevsky (“In the whole world there is no deeper, no mightier literary work. This is, so far, the last and greatest expression of human thought… And if the world were to come to an end, and people were asked, somewhere: ‘Did you understand your life on earth, and what conclusions have you drawn from it?’ – man could silently hand over Don Quijote”).

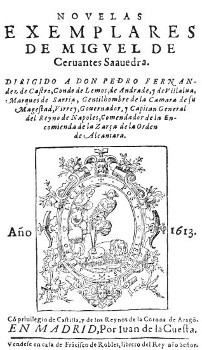

Title page of Novelas Exemplares, 1613. Source: Wikicommons.

By the way, Don Quixote was not the only book Cervantes wrote. Until the present day, his Exemplary Novels are also worth reading, in which he contra-poses the outdated sense of honor of his day with a new concept of the human being. As a case in point, a father consoles his daughter who had been abducted and hence wasn’t allowed anymore to show her face in the then ever-so respectable society: “…let it not distress you so much to be dishonored in your ownself in secret. Real dishonor consists in sin, and real honor in virtue. There are three ways of offending God; by thought, word, and deed; but since neither in thought, nor in word, nor in deed have you offended, look upon yourself as a person of unsullied honor, as I shall always do, who will never cease to regard you with the affection of a father.”

It is easy to see that Cervantes didn’t just address the woman who had become the victim of a man’s wrongdoing but that he also had himself in mind when he wrote these words.

Statue of Miguel de Cervantes in Madrid by Joan Vancell Puigcercós, 1892. Photograph: Luis García / http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.en

Miguel de Cervantes died on 22 April 1616 at the age of 69. Two days before, he had finished his work Persiles and Sigismunda. He was laid to rest in the monastery of the Trinitarian Order at Madrid, clad in a Franciscan habit. Until the last moment, he was grateful to this congregation that it had rescued him from the hands of the pirates in Algiers once.

The complete text of “Don Quixote” is available online and free of charge, for instance on Project Gutenberg.

If you prefer to listen rather than read for yourself, here’s a BBC broadcast that discusses why de Cervantes’s work has come to such fame.

You can visit the Spanish Royal Mint here.