Globalisation in Roman times: Trade with India

Along with the reign over Egypt, Augustus also seized control over a commercial route that had been increasing wealth in the country on the Nile since Ptolemaic times. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, which was most probably written during the middle of the 1st century AD, describes the way to India with all important stations in great detail.

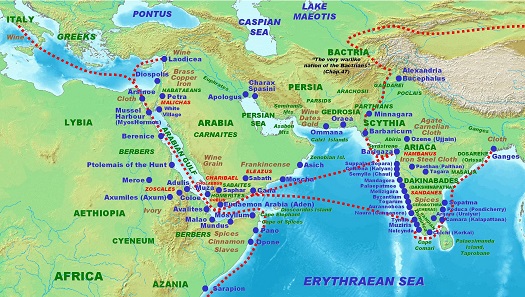

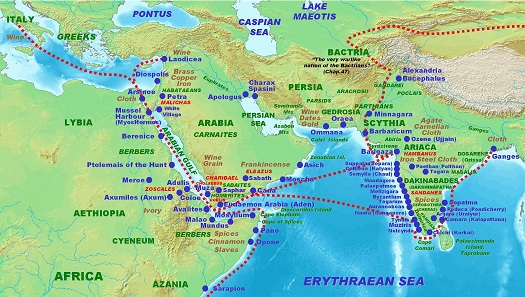

The commercial route to India in Roman times, as described by the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea in 1st century AD. Map: PHGCOM. GNU / CC4.0

Going up the Nile delta and through the Bubastis Canal, which had already been built in ancient Egyptian times and was renovated by Trajan, the ships sailed into the Red Sea. The journey went on into the Persian Gulf and from there the trading ships sailed to the east. They used the Monsoon winds, which the Roman-Egyptian seamen were experts on: In late summer, the northeast winds would take the Roman ships to India and in February the merchants would return with the monsoon that was then blowing southwest. Their goals were the Indian trading harbors of Barigaza and Muziris, further south, where there was even an imperial temple, as we can learn from the Tabula Peutingeriana. This should be conclusive proof that the traders from the Roman Empire were not just passing visitors, but instead they had built trading posts. Starting at Barigaza, the merchant ships sailed along the coast heading north to the area of today’s Pakistan or – starting at Muziris – they sailed south through the Palk Strait between India and Sri Lanka until they reached the Ganges Delta, where China and its silk production were fairly close.

Titus, denarius 79-81, 80. Rv. Elephant. From Künker sale 288 (13 March 2017), No. 492. Estimate: Euro 150.

India had a lot to offer to the Romans. Spices of course, like the overly important pepper, cloves and cane sugar. But they also imported ebony wood and dyers like indigo, not to forget wild animals. The Roman circus audience could not get enough of Indian tigers, rhinoceroses, elephants and boas. Roman coins thus often feature the impressive Indian elephants, easily recognizable by their comparatively small ears. A denarius from the upcoming Künker auction, minted in 80 AD, the year, in which the Colosseum was officially inaugurated, depicts an example.

Diva Paulina. Denarius under her spouse Maximinus Thrax, 235-238. Rv. Peacock carrying the deceased empress to the gods. From Künker sale 288 (13 March 2017), No. 760. Estimate: Euro 600.

Peacocks, too, had to be regularly imported. They were needed for the funerals of Roman empresses, after all. The ceremony required that a peacock flew away from the funeral pyre to take the soul of the empress to the gods.

An Indian tiger being captured to be killed in some animal fight for the entertainment of the Romans. Mosaic from the Villa Casale / Sicily. Photo: KW.

On exchange, the Roman merchants brought wine – ideally Italian wine, and copper, tin, lead and elaborately crafted luxury goods. It was mostly gold and silver coins that went to India, much to the annoyance of the Roman politicians. In his Natural History, Pliny the Elder already complained: “By conservative estimations, India, China and the Arabic Peninsular deprive our empire of one hundred million sesterces per year. This is how much we pay for our luxury and our women!”

Indian imitation of a Roman aureus. From Künker sale 288 (13 March 2017), No. 680. Estimate: Euro 1,000.

One hundred million sesterces per year! That is one million aurei! A massive amount, one would think and easily assume it to be an exaggeration.

The model: Septimius Severus with his spouse and his sons Caracalla and Geta. Aureus, 201, Rome. From Künker sale 288 (13 March 2017), No. 679. Estimate: Euro 30,000.

But there is a document that accounts for one merchant’s share of the shipload. And he transported 700-1,700 pounds nard oil – a word most busy church-goers will surely recognise from the New Testament: Mary anointed the feet of Jesus with nard oil worth 300 denarii, which Judas Iscariot deemed an awful waste. (Joh. 12, 1-7) And surely she used a vial that did not contain a “pound” of oil. Aside from nard oil, our merchant also transported over 4,700 pounds of ebony wood and almost 790 pounds of textiles. The entire value of his share is being estimated at 131 talents, a sum for which he could have bought around 970 hectares of prime Egyptian farmland at that time! And this was just one part of the shipload, albeit an especially precious part. It is estimated that one ship transported about 150 units.

Another Indian imitation of an aureus. From Künker sale 288 (13 March 2017), No. 669. Estimate: Euro 600.

The best evidence for the scope of the trade between Rome and India are the many aurei and denarii, mostly from the 1st and 2nd century, that were found in India. They are proof of the constant outflow of precious metal that Pliny describes. This only subsided when the eternal city had to deal with the barracks emperors and thus was too engaged with its own problems, so that the demand for luxury goods decreased. Our imitation coins showing the face of Emperor Septimius Severus are most probably from those times. They prove that India had gotten used to Roman money. When the imported coins were not enough for their own requirements anymore, they imitated them.

Trade continued, but not on the same scale as during the 1st and 2nd century AD. And when the Arabs conquered Egypt in 639/40, they took over the trading route. Europe was left out. It was only after the crusades that the formerly adored goods from the Far East should reach the West on a regularly base again.

The Künker Auction at which these coins will be offered can be found here.

And the relevant CoinsWeekly auction preview can be read here.