War is the father of all things. A short history of the art of besiegement: Part 1

translated by Christina Schlögl

in memoriam Georg Baums

When Constantinople trembled under cannon fire on 6 April 1453, this did not exactly constitute the beginning of a new era of warfare. However, the cannons did not only make the city walls collapse, but they also destroyed the medieval notion of fortresses.

Sigismundo Malatesta. Bronze medal 1446. On the reverse: view of fortified Rimini. From Künker sale 282 (2016), No. 4478.

Fortresses until the emergence of firearms (until 1500)

It had stayed the same since the era of the Roman emperor Diocletian (284-305). In the occident, people were relying on fortresses that had not changed since Antiquity. In fact, some were using defence works, built by Roman or Byzantine emperors, until the late Middle Ages. Shortly before its conquest, Constantinople, for instance, had still been proud of its city wall, 22 kilometres long, built by Emperor Theodosius in 423/4(!). It is a good example for the obstacles invaders had to face up to the 15th century when trying to conquer a big and powerful city: There were polygonal fortifications that made optimal use of the natural protection provided by the geographical location. There were towers in the wall at regular distances. They were used to open gun fire at intruders. Sometimes, there was an additional wall in front of the main wall, which formed the outer defence line. A city moat before the outer wall would provide further protection. A dam over the castle moat led to the guard gate and the dam was secured by an additional gate on the other side of the moat. Such a fortress protected the defender against all kinds of assault weapons, mostly catapults, which had also been in use since Antiquity. They were able to sling stones as heavy as 10 hundredweights.

Dordrecht / Netherlands. Counter 1595 on the battle of Bislich. On the reverse, a raiding patrol is trying to breach the fortified tower, using a ram bow. From Baums Collection, Künker sale 116 (2016), No. 4246.

And let’s not forget the huge battering rams that were preferentially used to break through the gate. Another important part were the bergfrieds, high towers which enabled the attacker to fight on the same level as their enemy, and mines, subterranean corridors which were dug very time-consumingly in order to break down the city walls. All of these techniques were used until well into the 15th century.

Turkish cannon from the middle of the 15th century. It is the largest and heaviest preserved artillery piece of its time. That’s what the cannons of Urban, used to fire at Constantinople, must have looked like. Today it is at the Royal Armouries at Fort Nelson, Portsmouth. Photo: Gaius Cornelius. No copy right limitations.

These weapons all had one thing in common: They were all used to wear down a stable wall enough to assault. The new fire weapons that were used since the beginning of the 14th century, did not bring any major change to this tactic. The date of the first use of a cannon at a besiegement is still debated about. One possible date is the besiegement of the Italian city of Cividale of 1321. In any case, the documentation of firearms starts to become more frequent in the 20ies of the 14th century.

But many only realised, just how effective this new technique was, when Constantinople was conquered – taken by storm – after 6 weeks of heavy fire on 28 May 1453. This incidentally did not happen by a breach in the wall but because there was a traitor. The Hungarian cannon builder Urban became famous in all of Europe. A feeling of menace emerged in Europe. Due to this new weapon, people stopped feeling safe behind their walls and felt constrained to develop mew fortification models to withstand the powerful firearms.

Fortifications since the regular use of firearms (1500-1650)

First, it was necessary to reinforce the walls so that they would offer better resistance against the new, heavy and moveable guns. The simplest idea was the best one: People raised an earth mound behind the wall that would take the force of the shot. On top of the mound, defenders were able to install their guns against the invaders. The high medieval stone walls with their wooden walkways proved unsuited for defence. They were substituted with lower walls that only had a layer of stone at the front.

Schaffhausen. Gold medal of 20 ducats no date (second half of the 17th century). On the obverse, you can see a panorama of the city as seen from the right Rhine riverbank. At the very right, the fortress Munot. From Künker sale 285 (2017), No. 135.

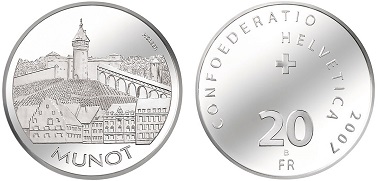

Evidence of this change can still be seen in Schaffhausen at the Rhine until today. The Munot is still there. It is part of a fortification (that was never built) that should have been built following suggestions of the painter Albrecht Dürer. Incidentally, he was the first writer since Antiquity who concerned himself with fortresses. His book is said to be the first one of an entire flood of theoretical treaties. The Munot is a round bastion where cannons can be installed on top to fire at the enemy into every direction. Inside the bastion, there were different rooms to keep provisions and shelter the garrison. In contrast to former fortifications, the moat is greatly widened and reinforced.

Switzerland. Commemorative coin 2007. Photo: Swissmint.

Such a round bastion had the great disadvantage that the area in front of the wall base could not be fired at from neighbouring mounds. If the enemy had reached the wall, he could attach scaling ladders without hindrance. Thus the shape of the bastions had to be changed. They became regular polygons and every architect and theorist had his own ideas about the relation of the different sides to each other.

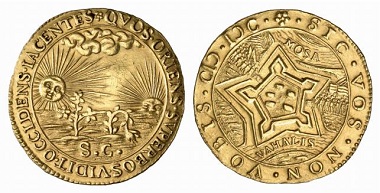

Saint Andre / Gelderland / Netherlands. Gold jeton around 1600. On the reverse: ideal fortification. From Baums Collection, Künker sale 116 (2006), No. 4229.

The most important obstacle and the most important component were not the high city walls but the moats with their walls. By digging a moat, the builder would obtain enough material to build his mounds. The mounds were faced with a stone wall. The inner wall of the moat was called scarp, the outer wall was called counterscarp. Embrasures in the scarp permitted shooting at the level as the attacker. And moats could certainly be flooded. If the water had reached a height of 1,80m, one could assume that storming the city was no longer possible. Behind the system of moats and outworks, the rampart was built. It had different bastions which all had different shapes, just as there were all types of outworks. The theories and ideas of the different systems was called “Manieren” in German, which best translates to “manner”, i.e. someone’s particular way of doing something.

The old Italian fortress had long (250m to 300m) unfortified wall sections between the polygonal bastions. The bastions ended at a relatively shallow angle. This was a great advancement in comparison to the round bastions of Dürer, but it still had the deficit that one could only really fire straight ahead.

Nijemegen / Netherlands. Medal 1702. The reverse shows gunfire as seen from a bastion. From Baums Collection, Künker sale 116 (2006), No. 4268.

The Italian manner was improved in Germany by an architect called Daniel Speckle (1536-1589). He determined the angle of the front bastions at 90°, so that enough space was left on one side to place cannons and a large radius for fire on the other side.

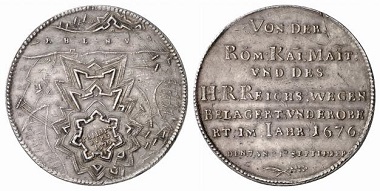

Philippsburg / Netherlands. Medal 1676. The reverse shows the later development of the idea of a hornwork. From Baums Collection, Künker sale 116 (2006), No. 4609.

The individual bastions were protected by an additional fortification on the bastion. Thus the defender could keep fighting from an even higher spot after the enemy had stormed the first step of the bastion. The outwork and the hornwork were further progressions of this stage. They made it even more difficult for the attacker to advance.

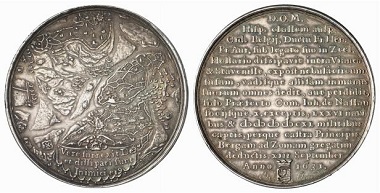

Bergen op Zoom / Netherlands. Medal from 1631 by Jan van Loof. As you can see on the obverse of this medal, water played a crucial role in the defence works of the Dutch cities. From Baums Collection, Künker sale 116 (2006), No. 4205.

The “Altniederländische Manier” (“Early Netherlandish defence manner” in loose translation) was created during the Dutch War of Independence. It was born out of sheer necessity. The many small cities had no defence and no money. Thus effective defence works had to be built from the ground up, quickly and cost-effectively. And they literally took the ground up. They built embankments in the style of the Italian manner, reinforced them with fascines and brushwood and cover them with grass. A second, lower mound was built in front of the main one to allow firing from two levels. Additional outworks were put in front of the faussebraye – demilunes and horn- or crownworks, if a certain side seemed particularly vulnerable to attack. The spaces in between could be flooded. Thus a direct attack had become impossible. Now the Dutch had only the cold and the ice to fear, as it would enable the invaders to walk up to the wall without getting their feet wet.

In the second and last part of this article, we will have a look at the changes, the large mercenary armies of the Thirty Years’ War brought to the fortress war, and what part Vauban, Louis’ fortress architect, played for the besiegement.