Erasmus of Rotterdam in Basel – part 1: The art of giving

translated by Christina Schlögl

Erasmus of Rotterdam was born as the second son of a priest and his housekeeper sometime between 1464 and 1469. In those days, this was not yet considered an indelible disgrace. These illegitimate sons were often granted a dispensation, which gave them equality to children born in marriage. Many progressive priests deemed celibacy pointless anyway and expected it to be abolished. Just think of the Salzburg archbishop Wolf Dietrich von Raitenau (prince-archbishop of Salzburg from 1587-1612), who had 15 children with his companion Salome and did not even consider hiding his family.

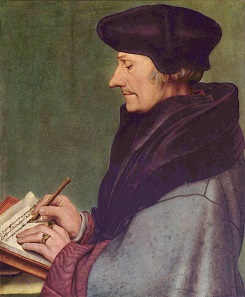

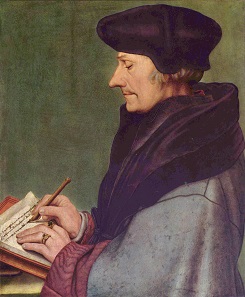

Erasmus of Rotterdam. Painting by Hans Holbein Junior. Kunstmuseum Basel.

Source: Wikipedia.

In any case, the young Erasmus was carefully raised by his parents and received the best education available at the time. In 1483, both parents died from the plague. Erasmus had to get by on his own.

Gifts as livelihood

He decided to join the Augustinian canons. A bad decision, since staying in one place was not a suitable lifestyle for the student, who had been ordained to the priesthood in 1492. As a consequence, he grasped the opportunity to work for the bishop of Cambrai. He left the monastery and travelled the world as a private scholar from then on – in close contact with high and highest rank personas. Be it Henry VIII or Charles V, Erasmus knew them and influenced them all when they were still young men.

As a priest and member of the Augustinians, Erasmus could not accept work in a traditional sense. And yet, he still became rich through his writing. Of course he neither earned royalties nor advances of publishers. After all, concepts like copyright did not exist in the early 16th century. There was a different system: At that time, everyone was in a sort of network of gifts and favours. Adhering to a strict set of social conventions, every gift and every service was met with a return gift or a return service. The value of the return gift was precisely adapted to the social rank of the giver and the receiver, as well as the importance put on the respective relationship. If a priest gave his pen friend a few rare plants for his garden, he had to return the favour. Categorically. With money, with a book, or maybe with an antique coin.

And of course, a clever man – and Erasmus von Rotterdam was quite clever indeed – could use this system by giving gifts to men of higher social rank, who then had to show how deeply they were honoured by this renowned writer’s gift and send a return gift of much higher value.

Medal on Erasmus, from his private estate. 1916.288. Historisches Museum Basel, Photo: A. Seiler.

A medal for Erasmus

One frequently used gift in this context was a medal from Erasmus with his own image as effigy. The Historisches Museum Basel has this specimen in their permanent exhibit. It is particularly special, since it verifiably came directly from the estate of Erasmus.

He had this medal minted in 1519 by the Antwerp-born artist Quentin Massys (ca. 1466-1530). The obverse showed his portrait with a modest beret and a not-at-all modest fur collar. Theoretically, an Augustinian could never have posed in such precious clothes, but Erasmus had received a papal dispensation in 1517 which had freed him of his monastic residential obligation once and for all and allowed him to live his life as a secular priest.

The humanist’s name was modestly abridged: ER – ROT. Everyone who would receive the medal would know that it came from ERasmus of ROTterdam. The Latin and Greek inscriptions on the other hand are all the more sophisticated: “Image made a true-to-life image” (in Latin) and “The scripts will show a better image” (in Greek).

The reverse depicts Erasmus’ personal symbol, the Roman god Terminus with the motto CONCEDO NVLLI – I give way to no one. This depiction was the personal symbol of Erasmus. He also used it to seal his letters. It was a misinterpretation of a gift he had gotten from an illegitimate son of the Scottish king Jacob IV (1473-1544/5). He gave him a ring that showed the Greek god Dionysus. However, this god of ecstasy did not exactly fit the concept of a humanist and a priest, which is why Erasmus instantly happened to misunderstand (or chose to misunderstand) the image and interpreted it as the Roman god Terminus. With this image on the reverse, Erasmus laid claim to never ending fame, because he saw Terminus as the bringer of death. The inscription reads “Death is the last line of all things” (in Latin) and “Remember the end of a long life” (in Greek).

Erasmus was one of the people who made medals as a medium popular north of the Alps. While they were already widely known in Italy, they were not prevalent in Germany yet. To Erasmus, these numismatic valuables were not collectables, but means of communication, a relatively cheap method to send his image to his admirers (and get a gift from them in return.)

The fact that Erasmus tried to convince Dürer to make a copper engraving of him, tells us for certain that this was actually the reasoning behind it all, because copper engravings would have been even cheaper in production. In the end, he ended up producing a struck medal with a much smaller diameter than the cast medal. This also lowered the production costs dramatically.

Medal on the Polish king Sigismund I, from the estate of Erasmus of Rotterdam. 1893.367. Historisches Museum Basel, Photo: P. Portner.

A gift from Poland

Now, what did Erasmus’ return gifts look like? This gold medal with the portrait of the Polish king Sigismund is a good example. It is also part of the permanent exhibition at the Historisches Museums Basel and it was part of Erasmus’ private estate. It weighs almost 82 g, which means that it had an impressive metal value. This generous donation came from Severin Boner, councillor and finance expert of the Polish king. One of his sons had lived at Erasmus’ home for a while. Erasmus had further developed the direct connection to the Polish nobility by dedicating his edition of the comedies of Terentius to the sons of Boner in March of 1532. Now he could be sure to get a generous gift.

Father Boner sent his own medal (36 g gold) and the medals of his lord (82 g gold) to Erasmus. He added a prim letter which stated that the precious material of the medals would constitute a symbolic equilibrium with the appreciation he was holding for Erasmus. It is an indication of Boner’s tremendous urge to deliver his generosity to posterity, that he had the reverse of the heavy gold medal engraved as follows: Severin Boner gave Erasmus of Rotterdam this gift (in Latin).

Due to its high value, Erasmus was also supposed to explicitly mention the medal in his will and leave it to Bonifacius Amerbach: And one gold coin with the king of Poland on it.

The testament of Erasmus

And thus we have come to the reasons why the estate of Erasmus can be found at the Historisches Museum Basel, of all places. He had made the city at the Rhine his favourite residence, because a very busy printer, Johann Froben (ca. 1460-1527) had established himself in Basel and had brought Erasmus back to his home town.

Bonifacius Amerbach. Painting by Hans Holbein Junior. Kunstmuseum Basel. Source: Wikipedia.

Froben had taken over the print shop of Johannes Amerbach (ca. 1441-1513) whose son Bonifacius (1495-1562) had quit the printing business to teach jurisprudence at the University of Basel. Erasmus started to appreciate the witty jurist, who had excellent connections to Froben. Did Amerbach help Erasmus in 1532 to receive papal dispensation to let him bequeath his possessions as a former priest and Augustinian?

In any case, the great humanist appointed his friend as heir and executor on 12 February 1536. After only a short time, on 12 July 1536, Erasmus of Rotterdam died. The fact that he was buried at the Münster in the reformed city of Basel, despite being a Catholic priest amidst times of religious debates about the reformation, should be more than enough evidence to show how highly people thought of him.

In the second part, you can read what Bonifacius Amerbach found in the estate and how he administered the inheritance.

You will get to the website of the Historisches Museums Basel here.

Where can you find more information on the afore-mentioned Wolf Dietrich von Raitenau? In CoinsWeekly, of course.