Big price for an emergency coin

7,500 Euros, that was the pre-sale price tag the Munich auction house and coin trading company Gorny & Mosch had attached to a 100 litra piece of Dionysius of Syracuse. It was a rather reasonable estimate for that type of coin.

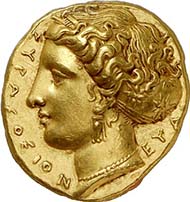

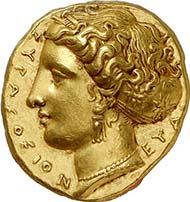

SYRACUSE (Sicily). Dionysius I., 406-367. 100 litra, 406-405 B. C. Signed masterpiece by Euainetos. Franke-Hirmer 46, 128 (this specimen). Extremely fine. From auction Gorny & Mosch 190 (2010), no. 65. Estimate: 7,500 Euros. Realized price: 66,700 Euros.

The pieces with Arethusa on the one side and Herakles strangling a lion on the other, created by one of the best die cutters in those days, cannot really be labeled rare. They show up in auctions from time to time. This piece, however, was something special. Whereas small pockmarks are usually discernable on the cheek of Arethusa – obviously the die had been put aside for some time, it had rusted and when reused left traces of rust on the coin’s surface –, whereas the reverse often shows a light to heavy double strike, the piece offered with Gorny & Mosch was perfect which had its immediate effect on the price. It rose from the estimate to the end result of 66,700 Euros – that is more than ten times the initial price.

Greeks and Carthaginians

Our coin was made in the last years of the 5th cent. B. C. under the rule of the notorious tyrant Dionysius I of Syracuse. Back then, the entire Greek world was in turmoil. The Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta (431-404 B. C.) for supremacy in Greece had already spread itself out. In Sicily, a local conflict that actually happened far away from the big centers of power in the South-West of the island, provoked a storm of events. The age-old rivalry between the cities of Selinunte and Segesta took on a global political scale when Syracuse cast its lot with Selinunte – surely not out of friendship but in the hope of gaining influence towards the Carthaginians in West Sicily. Segesta, on the other hand, was on the part of the Carthaginians by tradition and had entered a contract with Athens before so that Athens “felt compelled” to come to the rescue of his ally.

The fountain of Arethusa in Syracuse. The city goddess of the island did not possess an impressive temple as sanctuary but a humble fountain. Photograph: Giovanni Dall’Orto / Wikipedia.

For Athens, the Peloponnesian War did not work out as planned – it welcomed, therefore, the excuse to campaign against Syracuse being the enemy of one’s own ally Segesta, in the overall hope that seizing rich and powerful Syracuse would have resulted in a shift of the balance of power in favor of Athens again.

The Sicilian Expedition, however, became a disaster. The Syracusans utterly defeated the Athenian forces and sentenced the survivors to hard labor under horrible conditions. Segesta subsequently called the Carthaginians for help. They likewise sniffed a chance and conquered one Sicilian city after another.

Dionysius I.

In the meantime, Dionysius I had assumed power in Syracuse. Officially the city was a democracy in those days – or rather an oligarchy since the real power was divided amongst few. Dionysius was wary about changing the constitution. On the contrary, he let himself be proclaimed – in accordance with the law – strategos autokrator, that is Governing Commander. Given the imminent threat posed by the Carthaginians, Dionysius managed to further expand and secure his position. Syracuse being rescued by him from the Carthaginians surely pulled its weight, although the Carthaginian army was not depleted by the Syracusan troops but by a plague. Hence, Dionysius negotiated a compromise peace; he waived a major part of his former areas of influence of Syracuse but, in doing so, warded off any further threat by Carthago – for the time being, that is, since cunning tactician Dionysius was already contemplating his next moves.

Gold emergency coins

Our coin, its missing date notwithstanding, was surely produced as emergency money in the most critical phase of the war between Syracuse and Carthage, in 406 / 405 B. C., when the Carthaginian army had moved right at the gates of the city. A gold coin served as emergency money? Yes, of course, in the Greek poleis from the late 6th to the middle of the 4th centuries silver was the dominating metal for coins, bronze was used only on a small scale from the beginning of the 5th century. Most of the famous “owls of Athens”, for example, are made of silver; the gold, which was stored as a quasi strategic reserve on the Acropolis, was coined only in times of emergency. That happened at the latest stage of the Peloponnesian War, in 407 / 406 B. C., when Sparta blocked Athens’ access to its silver mines in Laurion, hence shortly prior to our coin.

Remains of the city wall built under Dionysius. Photograph: Giovanni Dall’Orto / Wikipedia.

But what was the money needed for, for trade, as circulation money? The latter seems highly unlikely because a gold coin was and still is too precious to be used as “change”. More important was that the troops and the allies had to be paid. Namely Dionysius was renowned for his armies of mercenaries – and they wanted to see money; otherwise, they would not have hesitated to join the enemy.

The best die cutters

It is remarkable that Dionysius did not appoint just any engraver to quickly produce the very dies but resorted to the best of their craft which were then working in Syracuse. Apart from Euainetos, who made the die of our piece, there was Kimon; these two created, apart from the gold 100 litra piece, namely the famous dekadrachms with Arethusa and the galloping quadriga.

Our coin, too, shows the fountain nymph Arethusa as symbol of the city of Syracuse. The reverse depicts Herakles strangling the fierce lion of Nemea – the first of his twelve deeds. Does this refer to current events? Herakles / Syracuse / Dionysius as victor over the imminent danger posed by the lion / Carthaginians? Is it by any means possible that Dionysius wanted to hint at his further plans meaning that this was “only” the very first of his deeds?

Much remains hidden in the dark, but one thing is for sure: the proud buyer has acquired a magnificent specimen of this historically significant series!