Gold for the coronation

by Andreas Urs Sommer

translated by Christina Schlögl

If there were kings and emperors to be crowned in numismatics, Albert M. Beck could certainly claim the right to a throne. But Albert M. Beck does not need a crown in order to be the undisputed master of numismatic communication, seeing as he founded the magazine “Münzen-Revue”, wrote books and initiated the World Money Fair. The number of people who found their passion for numismatics through him is immeasurable. As I am part of this huge amount of people myself, I would like to gratefully award Albert M. Beck with every crown there is. Since I do not own any crowns though, I would at least like to give him this small crowning gift for his special birthday.

In the year 1092, the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos (gov. 1081-1118) decided to make his five-year-old son John II his future successor. On occasion of the crowning of the prince as co-emperor, Alexios had a series of special coins minted, that should document this memorable event for his contemporaries and future generations to come. There had not been strikings like this in Byzantium for centuries. Today, collectors seek for these objects from Alexios’ coronation issue, made from lead, billon and electrum due to their rarity and their extraordinary effigies.

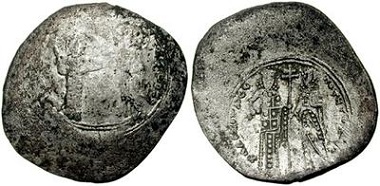

Lead tetarteron. Obv. […] The facing half-figures of Alexios on the left and his wife Irene Doukaina on the right, holding a long, simple cross between them. Rev. […] The facing half-figures of Saint Dimitrios (?) on the left and John II on the right, holding a long labarum between them. DOC 37. Weight: 4.45g, die axis: 0′.

Most of the time, these lead coins are badly preserved and therefore somewhat unappealing. It is more likely that they were used as commemorative tokens rather than currency. This specimen is from Thessalonika.

Billon aspron trachy. Obv. Jesus Christ on the right, the child John on the left, both facing. Jesus Christ with a beard, cruciform halo, pallium and colobium; he is crowning John with his right hand and holding the Book of Gospels with his left hand. John is wearing loros and crown, holding a globus cruciger in his left hand and a labarum-sceptre in his right hand. The field reads IC, XC right with ligatures above the letters. Rev. Alexios facing on the left, his wife Irene on the right, both with loros and crown, holding a long patriarchal cross between them, Alexios holding akakia in his right hand. MBR 59.16. Sear 1916. Weight: 3.60g, die axis: 30′.

The billon coins are more pleasant-looking. This is an example that was minted in Constantinople.

There are also some extraordinarily rare electrum-strikings of this type – which we will have to talk about later – but gold? Nothing so far!

But on 28 October 2015, at Subabsta 271 of the Barcelona auction house Aureo&Calicó, S. L., lot no. 4893 was auctioned for little money with the following image:

Covered by low-value Roman and Byzantine copper coins, one can (hardly) notice a coin that deserves exceptional attention. A few weeks later, in January 2016, the same coin – wrongly classified – was auctioned on a well-known internet platform by HHC Holding History in De Pere, Wisconsin, USA. Again, the object got lost in the clutter of the digital offering and got little to no attention.

Gold-“hyperpyron”. Obv. Jesus Christ on the right, the child John on the left, both facing. Jesus Christ with a beard, cruciform halo, pallium and colobium; he is crowning John with his right hand and holding the Book of Gospels with his left hand. John is wearing loros and crown, holding a globus cruciger in his left hand and a labarum-sceptre in his right hand. The field reads IC, XC right with ligatures above the letters. Rs. Alexios facing on the left, his wife Irene on the right, both with loros and crown, holding a long patriarchal cross between them, Alexios holding akakia in his right hand. Unedited, unique. Weight: 3.96g, die axis: 30′.

This is nothing less than the only documented gold coin from the coronation issue for John II, minted in Constantinople.

The coin was given to Dr. Hiltrud Müller-Sigmund from the department for geological and environmental science, division mineralogy-geochemistry of the University of Freiburg for metallurgical examination. On 26 February 2016, Hiltrud Müller-Sigmund determined the composition of the specimen with an error range of 2-3% as follows: “According to my analysis with the electron microprobe, the coin entails 60 wt% gold, 27-28 wt% silver and 7 wt% copper.” Thus the coin consists of 60% gold.

As we have seen, only electrum aspra trachea (Sear 1914), billon aspra trachea (MBR 59.16 / Sear 1916) and lead tetartera (MBR 59.22 and DOC 37) from the coronation issue of John II under Alexios from 1092/93 have been documented so far. That is why the standard literature has assumed that the large monetary reform in 1092/93 of Alexios I to stop the continuous devaluation of the old gold solidus (histamenon) and create a new base for Byzantine coinage, started with these special strikings. With the start of the standard emission of Alexios I in 1093, one gold hyperpyron of 21 carat (87.5% gold) equals three electrum trachea with 5-7 carat gold (20-29% gold, cf. DOC IV/1, p. 193 and BNP II, p. 669). There are only two known specimens of the electrum aspron trachy from the coronation issue: One in Dumbarton Oaks (DOC 21), the other one in the Bibliothèque Nationale Paris. A metallurgic analysis has been done with the Paris specimen (BNP El/03). The result is rather surprising, as its fineness of 8 carat gold (33% gold) exceeds the supposed norm for the new denomination of the electrum trachy: “The Paris specimen gives a specific gravity reading suggesting a gold content of some 8 carats fine, which is high for the denomination, and which just may indicate that it was intended to form the third part of a theoretical pure gold coin rather than the third of a coin of some 21 carats fine, and therefore that it represents a brief preliminary phase of the reform” (DOC IV, p. 194). One could argue that 1 carat is a tolerable anomaly. But the newly introduced coin with its 15 carat or 60% gold now deviates from the norm by more than 100%. Consequently, in accordance with the standard of the monetary reform, this cannot be an electrum aspron trachy.

Scholars have propagated a well-proved norm for the coronation issue that has been strictly adhered to – the aforementioned monetary reform of Alexios I. However, at least two thirds of the available gold-/electrum material, i.e. two of three coins, do not fit into the norm. And we do not have any information on the composition of the third coin in DOC. Such a deviation of the theoretical norm is slightly too substantial to uphold the theory. Another conclusion suggests itself: Apparently the coronation issue for John II was not released with the standards of Alexios’ monetary reform after all.

DOC IV, p. 214 uses † to suggest a hitherto unknown first hyperpyron issue that should typologically resemble the coronation electrum- and the billon-trachea. Page 193 reads: ”In Dumbarton Oaks Studies 12 the existence of the gold hyperpyron with designs appropriate to the ‘coronation’ coinage of 1092 was tentatively postulated – not least in the hope of ‘flushing out’ a previously unrecognized or unappreciated specimen from a collection. No such coin has yet appeared, and to this extent the case for its existence is thereby weakened.” There is further speculation in DOC IV that the electrum trachy from DOC and BNP might have been “the highest denomination of the series, perhaps as a brief initial phase of monetary reform, and that it was only very shortly afterwards (that is, by March 1093) that the new denominational structure was completed by the issue of hyperpyra of regular design, which both provided what was for certain fiscal purposes a triple-nomisma and for all others the standard coin.” (DOC IV, p. 193) But now, with our specimen, we have a coin that has the double gold content of an electrum trachy but that is still lacking 6 carat to fit the characteristics of a full hyperpyron after the new norm of the monetary reform.

Two conclusions could be drawn: Either the coronation issue did not adhere to a denomination standard, but was instead minted from different metals as one saw fit – because this issue war not intended to be used as daily currency anyway. Or the monetary reform of Alexios was started in a completely different way than scholars have thought, namely with a standard gold coin that rather matched the devaluated histamena of Alexios’ predecessors Michael VII Doukas and Nikephoros III Botaneiates. In that case, it would not have been a refined gold coin after all. And we would hold this very coin in our hands: Its value is not the triple worth of an electrum trachy, like the later hyperpyron, but only the double worth of an electrum trachy. This would explain the relatively high gold content of the Paris electrum trachy, which is exactly half of the specimen at hand. Incidentally, the coins can be distinguished quite well: The coin at hand seems very golden while the Paris specimen appears very silver.

Let us dedicate this newly found gold coin to Albert M. Beck for his birthday – at least in virtual form.

Literature

BNP: Cécile Morrisson, Catalogue des Monnaies Byzantines de la Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris 1970.

DOC: Alfred R. Bellinger / Philipp Grierson / Michael Hendy: Catalogue of Byzantine Coins in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection and in the Whittemore Collection, Washington D.C. 1966-1973, 2nd edition 1992-1993, Vol. 4/1-2 and 5/1-2 1999

MBR: Andreas Urs Sommer, Die Münzen des Byzantinischen Reiches 491-1453. With a supplement: Die Münzen des Reiches von Trapezunt, Regenstauf 2010.

Sear: David R. Sear, Byzantine Coins and their Values, London 2nd edition 1987.

You will find more information on the author of this article in our numismatic Who’s Who.