Human Faces Part 14: Hadrian, Citizen of the World

with the kind permission of the MoneyMuseum, Zurich

Why is it that for centuries – or rather thousands of years – the head has served as the motif for the side of a coin? And why has this changed in the last 200 years? In this chapter of the series ‘Human Faces,’ you’ll hear about how the Greek beard made its way into Roman portraiture.

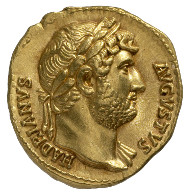

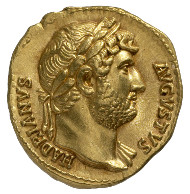

Roman Imperial Era. Hadrian (117-138). Aureus, 128. Head of Hadrian with laurel wreath facing right, delicate draping on his left shoulder. Rev. the Emperor as commander atop his rearing horse, riding to the right. © MoneyMuseum, Zurich.

When Trajan entrusted military power in the East to his great-nephew Hadrian, essentially making him his successor in the process, it was one of the Roman Empire’s greatest moments. Trajan could not have found anyone who was better trained, with better first-hand knowledge of the provinces, or who was more willing to constantly build on his knowledge.

The Roman senators, on the other hand, were not nearly as thrilled about their new emperor. To start with, they were embittered that Hadrian had relinquished conquests of his adoptive father, although it was already quite clear that they could only have been militarily defended at great expense. This emperor certainly did not represent the ancient Roman virtues of a ruthless conqueror. And – or at least so the senators felt – he mocked them all by flouting their views of decorum: Hadrian sported a beard, a clear sign of his rejection of the senatorial ideas of what constituted a worthy, dignified appearing Roman.

Architectural structures like the Canopus and the Serapeion in Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli reflect Hadrian’s experiences in the Roman Empire. Photo: Aquilifer / http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

And, in fact, this new emperor did not behave like his predecessors. Unbelievably, he treated the denizens of the provinces as equals. During his travels, he devoted more time to them and their concerns than he did to the Roman senators. That by doing so, Hadrian was actually creating the basis for the long continuity of the Roman Empire, was something that was not within the grasp of a Roman city senator. For us though, Hadrian’s foresight makes him the greatest emperor the Roman Empire had ever seen. It’s to his spirit, fertile imagination and panache that the provinces owed their being able to live in a state of peace and prosperity for almost two generations. Hadrian dreamed the dream of a society that included all citizens of the Roman Empire – united through the Roman laws, issued by a benevolent, patriarchal ruling emperor – with equal opportunity, but also equal duties and responsibilities for all those afforded protection by the Roman Empire.

But where equal opportunity prevails, it follows that some must sacrifice their privileges. In short, the senators hated Hadrian for his liberal-minded policies. And when the emperor died in July 138, they wanted to make him pay – In the senate, they made a motion for his damnatio memoriae. It was only when Antoninus Pius, Hadrian’s adopted son and successor, threated them, thus provoking a civil war in the Roman Empire, that the senators gave in and declared Hadrian a God.

In the next chapter, you’ll learn about vices that even a philosopher like Marcus Aurelius cherished.

All sections of the series can be found here.

The book ‘MenschenGesichter’ is available in printed form from the Conzett Verlag website. It soon will be translated to English. …