The unlucky emperor Clodius Albinus – a portrait study

Thomas Ganschow

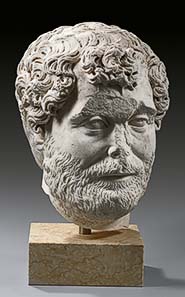

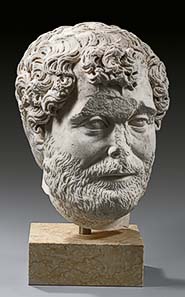

What a huge surprise when the company Gorny & Mosch – Giessener Münzhandlung auctioned off a Roman portrait head from the late 2nd cent. A. D. at auction sale 184 on December 18th, 2009. It was a high quality marble portrait in a remarkable state of preservation which some minor damages on the face could not impair. What was the name of the depicted? There is much evidence that it is an image of Clodius Albinus who eventually had to admit defeat when fighting over the throne of the Roman Emperor with Septimius Severus; that remains valid even though some deviations from the ordinary portrait type may cause irritation. Perhaps it was precisely the head’s mysterious aura that led to a lively bidding fight climbing from the original estimate of 45.000 Euros up to the unexpected sum of 149.500 Euros.

Portrait head of Clodius Albinus (?), marble. Roman, c. A. D. 193-197

From auction sale Gorny & Mosch, Giessener Münzhandlung 184 (2009), no. 8; estimate:

45.000 Euros – hammer price: 130.000 Euros.

“The Year of the Five Emperors” 193

The year 193 was one of the most eventful in Roman history thanks to the fact that it saw as many as five emperors who either exercised co-regency or reigned one after another: after Commodus was murdered on December 31st, 192, Pertinax assumed the reins of government at first. 66-year-old Pertinax was a veteran officer who, due to his rigid savings course, soon became unpopular especially with the military that was used to his predecessor’s generosity. It was only three months later that Pertinax, too, was assassinated. The following events are unparalleled in Roman history: the emperorship was more or less auctioned off, to the one that offered the Praetorians, i.e. the force of imperial bodyguards, the most precious gift of money. The new man was 60-year-old Didius Iulianus who also looked back on a remarkable military career and was only some years his predecessor junior. Strictly speaking, he should have foreseen what happened next: the soldiers in the provinces who had come away empty-handed denied the new emperor their loyalty and proclaimed their commanders emperor instead – in the hope that they would be lavishly rewarded: Septimius Severus in Pannonia (Hungary), Pescennius Niger in Syria and Clodius Albinus in Britannia.

The fight for the emperor’s throne

Now, the race for Rome had started providing the best chances of claiming the imperial throne for the one who reached it first. Pescennius Niger was at a disadvantage in the first place because he simply was too far away from Rome. Septimius Severus resorted to a trick: to prevent Clodius Albinus from beating him to the punch, he proclaimed Albinus Cesar, his designated successor, who was supposed to continue staying with his troops in Britannia. One might ask why Albinus accepted this offer in the first place – with his 46 years of age he was, after all, only one year Severus junior. Because of that, he had no real chance of taking over from his predecessor; plus, Septimius Severus had two promising sons. Perhaps Clodius Albinus was planning to let his opponent do the work and kill him afterwards. As soon as he resided as Cesar in Rome, there would be plenty of opportunity to put his plot into action.

If Clodius Albinus thought along these lines, he soon had to realize that he himself had been deceived – Septimius Severus had never intended to make him his successor. Rather, he wanted to have free rein to defeat Pescennius Niger who he had killed at the end of 194.

Another year passed before Byzantium fell where the supporters of Pescennius Niger had retreated to. Finally, Septimius Severus disclosed his true intentions: he declared Clodius Albinus enemy of the state leaving him with only one option: to take the bull by the horns.

After his troops proclaimed him counter-emperor he entered the battle against Septimius Severus only to be defeated at the beginning of 197 near Lyon. He was killed when fleeing from the battlefield.

Portrait head of Clodius Albinus (?), marble. Roman, c. A. D. 193-197

From auction sale Gorny & Mosch, Giessener Münzhandlung 184 (2009), no. 8; estimate:

45.000 Euros – hammer price: 130.000 Euros.

The marble portraits

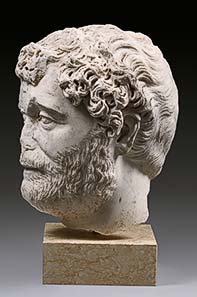

As long as Clodius Albinus was official Cesar of Septimius Severus, portraits of him were produced. These portraits show similarities to those of Septimius Severus aiming to publicly display their close connection; this portrait assimilation, as it is called, goes so far that it becomes difficult, at least for the modern viewer, to distinguish the two of them. It was Klaus Fittschen who, in his catalog of Roman portraits in the Capitoline Museums, recognized physiognomic differences and assembled the portraits of Clodius Albinus that have come down to us. All of them belong to a portrait type of which eight replicas are extant. This number alone suggests that the depicted must have been an important personality. The most characteristic feature of the portraits is the receding hairline framing a tuft of hair that falls into the forehead. Severus’ portraits do not show this receding hairline, his forehead is framed almost rectangularly. He has a longer beard that seems to be divided into two parts at the chin. Although our head does not conform in every single detail with the known portraits of Clodius Albinus, the first impression nevertheless suggests that this really is one of the rare images of the man who was deceived by Septimius Severus.

Denarius of Clodius Albinus as Caesar. Rome, 194-195. Rev. Minerva pacifera. RIC 7. From auction sale Gorny & Mosch 181 (2009), no. 2261.

Denarius of Clodius Albinus as Augustus. Lyon, 195-197. Rev. Aequitas Augusti. RIC 13(a). From auction sale Gorny & Mosch 176 (2009), no. 2373.

The coin portraits

The coins of Clodius Albinus show him with a less prominent tuft of hair in the forehead. The receding hairline, too, is less distinct to the effect that the forehead appears almost rectangularly framed, comparable to Severus in his marble portraits. Severus, in turn, is shown with curlier hair and a considerably longer beard than Albinus which is as voluminous as his head hair. This was done to emphasize the different status of the two: whereas the reigning emperor with his full hair has been moved to the divine sphere iconographically already, Albinus, with his short hair, is depicted as Cesar who has yet to gain laurels – even though, strictly speaking, that was not true. It comes as no surprise that Albinus was depicted with more voluminous hair the moment he was proclaimed emperor in opposition to Severus.

The relatively short hair of our portrait suggests that it is Clodius Albinus who is depicted here in his position as Cesar, not Septimius Severus. Some uncertainty remains, however, adding something mysterious to this portrait and thereby making it an object of desire.