Coloured Metal from Austria: Niobium Coins

by Daniel Baumbach, translated by Maike Meßmann

Actually, there aren’t so many metals that are and were used in coin production. On the one hand, there are the traditional options: gold, silver and copper/bronze. In addition, every now and then you can find platinum, palladium and sometimes titanium coins, as well as coins made from a number of base metals that are used by themselves or in the form of alloys: mainly tin, zinc, aluminium, nickel and iron. Thus, introducing a new coin metal is anything but commonplace. But it’s exactly what the Austrian Mint did when it issued a bimetallic coin with a niobium core for the first time in 2003.

Content

Why did the mint use niobium? Because it has exciting characteristics that were harnessed in Vienna.

Titanium as a Precursor to Niobium

Let’s go back to the time around the turn of the millennium. In 1992, the first coins with colour printing were issued. In the following years, colour coins conquered the market and collectors’ hearts. But many collectors had mixed feeling about these new, “painted” coins. The Austrian Mint, which has always been well-versed in technical matters, was looking for other options to make coins more colourful. By using a new metal, for example. The first results of these attempts were released in 2000. They opted for bimetallic coins with a silver ring and a titanium core. The metal was difficult to mint and had been used for the first time in coin production just shortly before – Austria was among the first nations to issue titanium coins.

The Austrian Mint’s first coin with a titanium core from 2000: 100 schilling, Communication / Millennium. Photo: Münzhandlung Ritter.

However, the colour of titanium isn’t exactly what one would call exciting, and a new, sophisticated minting technology also fell short of expectations. Nevertheless, the 100 schilling coins of 2000 and 2001 dedicated to “Communication” and “Mobility” were very impressive from the technical point of view.

These two titanium coins are often overlooked by today’s niobium collectors because, unlike their successors, they were minted in the times of the schilling currency. But regarding their motifs, mintage numbers and technical specifications, these innovative issues are closely related to niobium coins and a worthy addition to a collection of these Austrian issues.

Niobium? What Is Niobium?

To find a more suitable metal, the Austrian Mint collaborated with Plansee, a Tyrolean high-tech company specialised in metal. And indeed, after many experiments, they found a metal that could be well used for coin production: niobium.

Let’s first answer the question that most people were wondering about at the time: what the heck is niobium? Niobium is a rare metal that – like titanium – is mainly used in space technology and in the processing of steel. The peculiar name is derived from Niobe, a queen of Thebes from Greek mythology. And why was the metal named after this queen? Because it’s very similar to another metal: tantalum, which in turn was named after Niobe’s father, Tantalos. And why was tantalum named after Tantalos? Briefly said: because the metal’s characteristics reminded the chemist who discovered it of a story from Greek mythology. If you want to know more, Wikipedia will help.

Let’s get back to niobium. The metal is actually grey by nature, which at first doesn’t seem to fit the colouring options we’re looking for. But what’s exciting about niobium is that you can make the metal appear in a variety of colours. This effect is achieved by a process called anodic oxidation. It creates an oxide layer on the surface of the metal. Depending on how thick this layers is, the light refracts differently and gives niobium a different colour. Earlier experiments with titanium only succeeded in producing different shades of grey. But with niobium – which also does not require as much heat as titanium for this purpose – this process leads to a variety of iridescent colours.

Innovation and Tradition

The result of these experiments was the world’s first niobium coin, issued in 2003. It had a face value of 25 euros, a silver ring and a core of bluish niobium. Regarding its motif, it was very fitting that the innovative coin was dedicated to one of the great centres of innovation in coinage: the town of Hall and its 700th anniversary. Among other things, Hall was the first town to successfully mass-produce large silver coins, the first talers – although this name was not used until later. The negative of this first multiple silver coin, the guldiner of Sigismund called rich in coins from 1486, is depicted on the niobium issue. We see an impressive knight on horseback in full armour. The other side of the niobium coin features modern technology: the surveying of the town of Hall with then ultra-modern satellite technology – moreover, the design incorporates the then futuristic digital alarm clock font, which rather coaxes nostalgic smiles out of today’s observers.

The success of the first niobium coin was impressive and probably even surprised the Austrian Mint itself. The coin was issued at a mintage of 50,000 pieces at an issue price of 37.90 euros. They sold out quickly. And prices on the secondary market skyrocketed at the same pace. This was one of the reasons why so many people were interested in the 2nd issue one year later – the coins completely sold out via advance orders. As a result, the mintage number of the thrid niobium issue in 2005 was increased to 65,000 specimens and has remained the same ever since. From this point on, the initial hype was over and the mint was able to satisfy the demand, the increase in value remained rather modest. But the first coins and especially the Hall issue are sought-after collectibles and are today priced at around 450 euros.

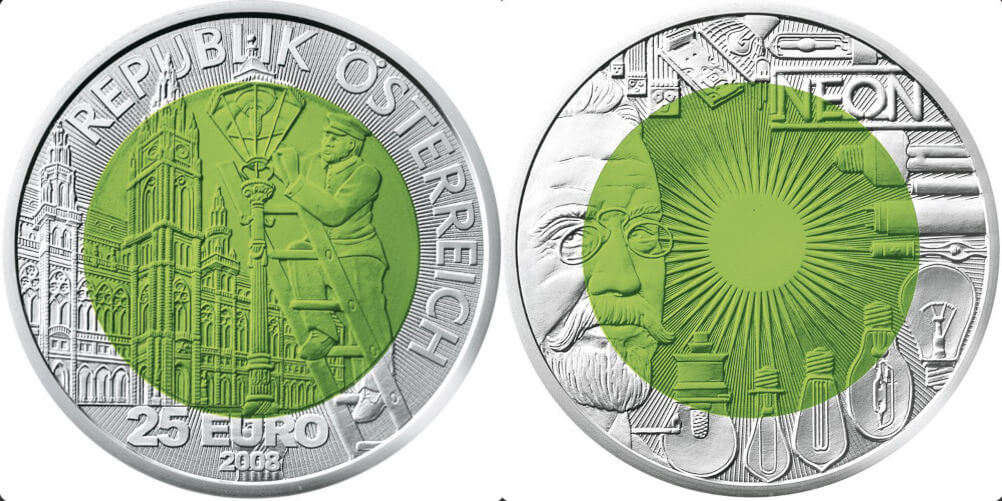

Since 2003, a new niobium coin of 25 euros is issued every year. The series does not have an official name, but some of the coins were released under terms such as “Technology in Austria” or “Fascinating Technology”. Earlier issues were dedicated to railway, aviation or tunnel construction projects. By now, the motifs are rather focused on visions of the future and science fiction, as the “little green man” on the current issue “Extraterrestrial Life” clearly demonstrates.

If you take a look at niobium coins issued since 2003, you can clearly see the progress that has been made during that time. Further research was done as to how niobium can be processed in an even better way. As of 2007, it has therefore been possible to create more radiant colours. The motifs also became more complex and detailed. A particular milestone was achieved in 2014 when the “Evolution” issue presented a multicoloured niobium core for the first time – this, by the way, is one of the coins that experienced an increase in value. Since then, all niobium coins were designed in two colours.

Reception

Even after almost 20 years, niobium coins enjoy great popularity among collectors. Experts regularly honour the technological achievements behind the issues with Coin of the Year Awards. In the last eight award ceremonies alone (2015-2022), the Austrian Mint’s niobium coins received the award in the category best bimetallic coins six times (!). Strangely enough, only the fifth niobium issue of 2008 received an award in the category most innovative coin.

However, it cannot be said that niobium did become an established coin metal – which might be due to the sophisticated production process. There are coins with niobium core from Latvia and Luxembourg, all of them produced by the Austrian Mint. Moreover, the Royal Canadian Mint, which is known for regularly picking up innovations from across the world, has produced some niobium coins since 2011. Niobium can also be found from time to time on non-circulating legal tender of island nations. Titanium colouring, the approach that had been rejected by the Austrian Mint before, is now also being successfully used: the British Pobjoy Mint, for instance, has succeeded in producing two-colour issues made from this metal.

Niobium coins started as an alternative for coins with colour application. The Austrian Mint’s series has been running successfully for almost 20 years. Of course, these coins have never become real competitors to the now almost ubiquitous colour-printed coins. And the Austrian Mint has obviously also produced coins with colour printing by now. However, the niobium series and its fascinating technology are an enrichment for the coin world, which has become a little more colourful thanks to these issues.