Frederick III of Denmark and Eben Ezer

by Ursula Kampmann on behalf of SINCONA

SINCONA’s Auctions 92 to 95 will take place from 21 to 25 October 2024. This article introduces one of the many rarities up for sale: a so-called “Ebenezer” coin from Denmark. The 4-Ducat specimen, besides being extremely rare, is also of great historical interest.

Content

The so-called Ebenezer issues are among the great rarities of Danish numismatics. Even the silver Ebenezer Krone is astonishingly rare. But the 4-Ducat coin is rarer still. Just seven specimens are currently known to exist; one of them lies in the Royal Coin Cabinet in Stockholm.

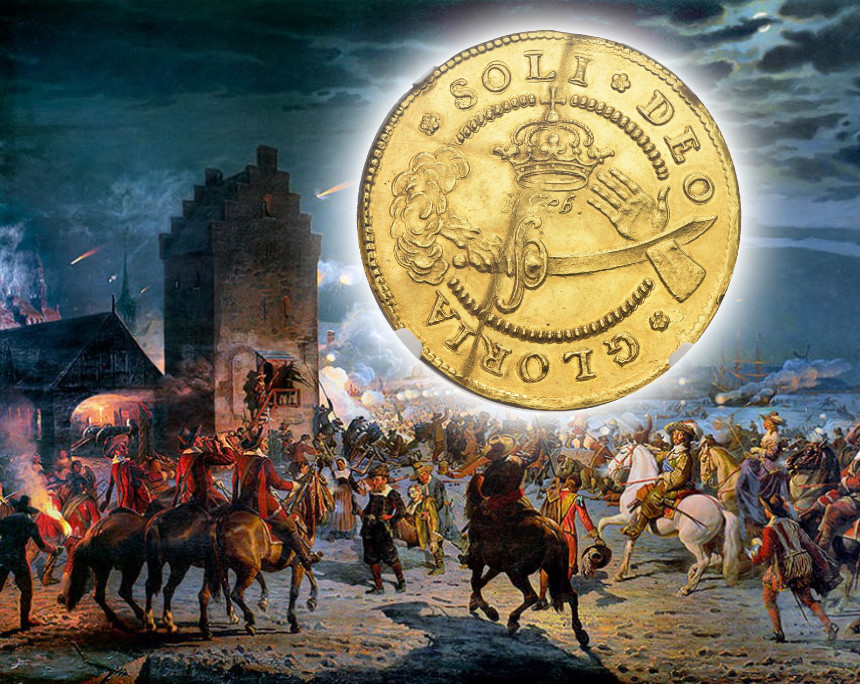

One of these specimens will be auctioned off by SINCONA in Auction 94 on the afternoon of 22 October 2024. One side depicts the hand of God, wielding a sword as it severs another hand reaching for a crown. The reverse features the monogram of Frederick III atop a stone, surrounded with the inscription EBEN EZER. Are you wondering what message this motif is trying to convey? Read on to find out.

Frederick III and His Difficult Legacy

Frederick III became King of Denmark and Norway on 8 May 1648. His predecessor had left behind a burdensome legacy, including significant debts and the resulting heightened influence of the nobility. Every time Frederick needed the approval of the nobility to impose taxes, they would extort additional privileges. Frederick was especially troubled by the nobles to whom Christian IV had married his illegitimate daughters and whom he promoted to high-ranking positions. Corfitz Ulfeldt, for one, sabotaged Frederick III wherever he could. Ulfeldt had negotiated the Peace of Brömsebro with Sweden in 1645, which ultimately proved to be the most difficult legacy inherited by Frederick. The terms of this treaty meant he was forced to forego not only the rich revenues of the province of Halland and the islands of Gotland and Ösel (now Saaremaa, Estonia) but also customs duties on Swedish merchant ships passing through the Öresund.

The march of Charles X Gustav’s army across the frozen Great Belt. Contemporary Swedish illustration by Erik Dahlbergh from 1658.

An Unsuccessful Attempt at Liberation

A proactive ruler, Frederick III immediately began to tackle one problem after the next. He charged Corfitz Ulfeldt with embezzlement and drove him from Denmark. Then he set about reconquering the lost territories. It seemed like a good time to strike; with the Swedish King Charles X Gustav engaged in war with Poland, his troops were far enough away as to embolden Frederick to launch a surprise attack.

But Corfitz Ulfeldt was to intervene yet again. He had fled to Sweden with his fortune, where he used 150,000 Reichstalers to recruit an army for the Swedish King, joining the ranks himself as an advisor. Frederick’s decision to declare war thus backfired; the Swedes plundered Jutland. They did not stop there though: in the winter of 1657/1658 – at the height of the Little Ice Age – the Belts froze over, enabling Charles X Gustav to lead his army from Poland to Denmark and reach the gates of the capital, Copenhagen, completely by surprise.

A Desperate Peace and the Siege of Copenhagen

Frederick III was forced to negotiate – with Corfitz Ulfeldt of all people. With gritted teeth, he agreed to treaty conditions that would later be referred to as the panic peace in German history books. On 8 March 1658, Frederick reluctantly signed a document that saw Denmark ceding one-third (!) of its territory. But even this was not enough to satisfy Charles X Gustav. At the Imperial Diet in Gottorp on 7 July 1658, he announced he would not rest until he had dislodged the Danish monarch from his throne.

With Swedish troops still stationed at the gates of Copenhagen, this was logistically unproblematic. After an initial assault on the capital failed, Charles X Gustav declared a siege to starve Copenhagen into capitulation. But this plan was hindered by the Dutch. After all, their profitable trade in the Baltic would be at risk should Sweden usurp the entire region. They sent a fleet of reinforcements and supplies to Copenhagen, leaving Charles X Gustav with no choice but to try to storm Copenhagen once again.

Students participating in the defence of Copenhagen. Historicist painting by Vilhelm Rosenstand from 1889.

The Assault on Copenhagen on the Night of 9 to 10 February 1659

The first attack was launched on the evening of 9 February 1659. During the attack, the Swedes had to abandon one of their assault bridges. These assault bridges played a central role in attacks on fortified towns, as they could be used to cross the unavoidable moats. The assault bridge left behind by the Swedes provided the Danes an opportunity to measure the standardised piece. It measured 36 feet. The troops of Copenhagen thus immediately set about removing the ice from the edges of the moats and trenches so as to ensure a 36-foot assault bridge would be insufficient to cross the water.

At 4 o’clock in the morning, the Swedish sounded the attack once again. One hour later, they began their retreat. 600 fallen soldiers were left behind at the city walls. An even greater number of men perished in the freezing waters.

Frederick III, 1648-1670. 4 Ducats 1659, Copenhagen. Only seven specimens known. Wavy flan. NGC UNC Details. Estimate: CHF: 20,000. From SINCONA Auction 94 (22-23 October 2024), No. 1616.

Israel’s Battle Against the Philistines

This victory is often alluded to in explanation of Frederick’s Ebenezer issues. One side clearly depicts the political situation: as the hand of the Swedish king reaches for the Danish crown, the sabre-wielding hand of God severs the hand of the Swede, thereby saving the crown. Soli Deo gloria – glory to God alone, declares the inscription.

But the Treaty of Copenhagen agreed in the wake of this victory was far from retribution. Frederick was forced to cede the entirety of Eastern Denmark and the heartland of Skåne. Moreover, all his subjects remembered the intervention of God in favour of the Swedes when He froze the Belts and enabled their crossing by the Swedish King. Those as biblically-minded as the people of the 17th century tended to associate this with Moses and his parting the Red Sea.

Frederick had to address this in his propaganda – and he drew on the Old Testament to do so. Book 1 Samuel 4-7 retells the story of Israel’s darkest hour, the loss of the Ark of the Covenant:

Israel suffered a devastating defeat against the Philistines. The elders expressed doubt toward God and wanted to force Him to help them. They retrieved the Ark of the Covenant from Shiloh and returned to the battlefield. But the Philistines defeated them once again. They triumphantly returned home with the Ark of the Covenant, placing it in the temple of Dagon in Ashdod. Upon entering the temple the next morning, the statue of Dagon was lying on the ground. They replaced it to its upright position, only to find it shattered the next morning. On the third day, all of Ashdod was struck with bubonic plague. This also happened in Gath and Ekron, where the Ark of the Covenant was subsequently taken. Only then did the Philistines decide to return the Ark of the Covenant to Israel.

Twenty years passed. The Ark of the Covenant had returned, but the Philistines continued to harass Israel. So the Israelites asked Samuel how they could attain victory over the Philistines. He advised them to rid themselves of all foreign gods and commit themselves to the Lord, which they did. Lo and behold, as the Philistine army approached, the Lord produced such a thunder as to confuse the Philistines and cause them to flee in panic. Samuel then took a stone, set it up and named it Eben Ezer: stone of help.

This stone is depicted on the coin together with the monogram of Frederick III.

An Ancient Biblical Message as Justification for Contemporary Politics

Frederick equated the deep humiliation Denmark had suffered with Israel’s situation in the battle against the Philistines. For him, the failed conquest of Copenhagen by no means represented the ultimate victory; the painful terms stipulated in the Treaty of Copenhagen were felt too keenly by all Danes for that. His coins looks to the future: only if the Danes grant him absolute rule and disempower the nobility can victory be assured. This is the most sensible explanation of the connection between Eben Ezer and the royal monogram. The inscription “The Lord will provide” can be interpreted to mean the development of the coming months would not be influenced by mortals but ordained by God.

Thanks to his significant and positive role during the defence of Copenhagen, the King had only lost little of his prestige. He was thus able to place responsibility for the events entirely on the shoulders of the nobility – an excellent scapegoat. The eradication of the nobility became conflated with a sort of moral repentance, to which Frederick alluded with the depiction of Eben Ezer. In October 1660, he disempowered the stænderforsamling (estates of the realm) in a revolutionary act.

Of course, there was resistance to this. Corfitz Ulfeldt – whom the Swedes had meanwhile exiled as a traitor due to the “lenient” terms he stipulated in the last peace – was back to his scheming ways in Denmark. When Frederick was informed by the Elector of Brandenburg that Ulfeldt had offered him the Danish crown, Ulfeldt was sentenced to death for treason. He managed to escape, however, making it as far as Basel where he went into hiding in the small suburb of Riehen. When word got out that there was a price of 20,000 talers on his head, Ulfeldt attempted to escape again, this time by boat across the Rhine. Did he die in the attempt? Or go into hiding under a false name? We will never know.

An Absolute Ruler by Decree

What we do know is that Frederick III was victorious in the battle against the nobility. He declared himself absolute ruler by decree on 14 November 1665. The meaning of this is explained in Article 26 of the King’s Law: “What has been stated or not explicitly stated in the foregoing regarding the sole rule of the King and his power and sovereignty can be explained in these few words: the King of Denmark and Norway is a free, absolute and sovereign hereditary King.”

This makes Denmark the only country in Europe to have introduced absolutism by law – and not even at the expense of a subsequent uprising. That Frederick was nevertheless unable to revise the terms of the Treaty of Copenhagen is another story.