French History in Coins – Part 1: Kings, Consuls and Emperors

written by Aila de la Rive, by courtesy of the MoneyMuseum, translated by Maike Meßmann

“Man is born free and everywhere he is in chains.” Jean-Jacques Rousseau, writer and philosopher, *1712, †1778

Throughout the 18th century, France was profoundly shaped by the ideas of the Enlightenment, until the French Revolution heralded a new age in 1792. This fascinating period is reflected in a remarkable way by its means of payment. We will start the first part of our journey through French history by taking a look at the coins and banknotes issued in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Content

From Revolution to Restoration

22 September 1792, the first day of year 1 according to the Revolutionary Calendar, marked the beginning of the modern era for France: France is a republic!

More than three years had passed since a hungry crowd stormed the Bastille in Paris on 14 July 1789 chanting “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity”, overpowering the guards and freeing the prisoners. Now the king had been deposed; many nobles left the country – and they took large sums of cash with them: France is close to bankruptcy.

The First Republic was rather short-lived. In 1799, a young general seized power of battered France. Napoleon Bonaparte (1799–1815) deposed the weak government – the so-called Directory – and installed himself as First Consul at the head of the state. Five years later, he crowned himself Emperor of the French. In this way, the small Corsican followed in Charlemagne’s footsteps: his goal was to revive the Holy Roman Empire – this time under French rule.

It goes without saying that the rest of Europe was not enthusiastic about these plans of making France a super power. Prussia, England, Russia, Sweden and Austria joined forces in an alliance; in March 1814, they took control of Paris. For the time being, this put an end to France’s political experiments: the Bourbon monarchs were restored to the throne – with Louis XVIII (1815–1824), a brother of the king that had been executed after the Revolution, assuming power.

But the country was to be shaken by a revolution once again in 1848.

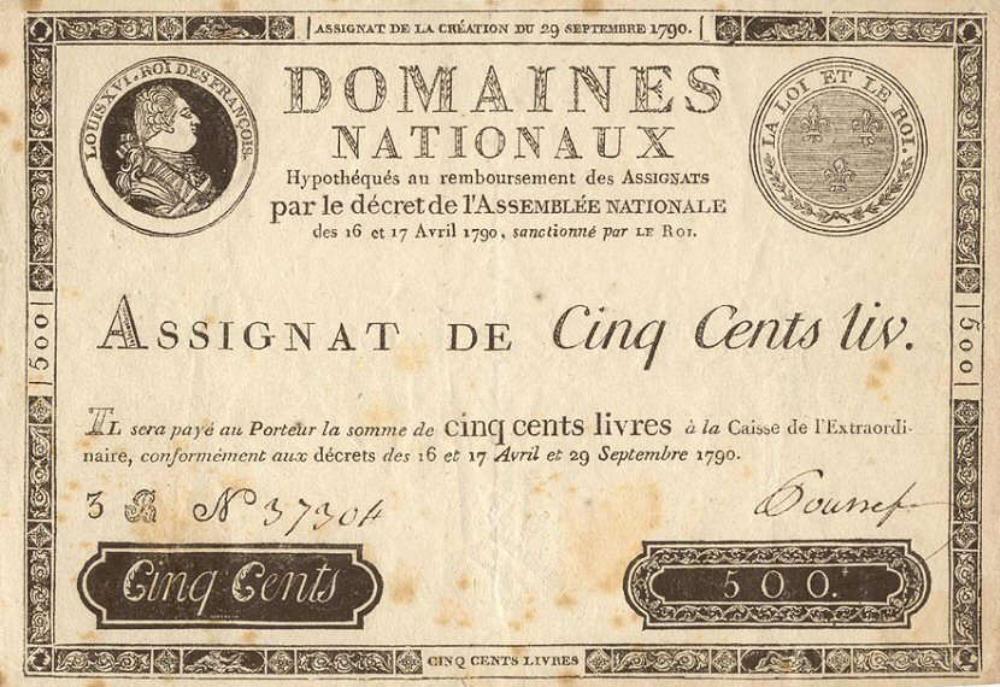

Kingdom of France. Assignat of 500 livres 1790, paper, Assemblée Nationale and Louis XVI. Photo: Public domain.

The Money of the First Republic

After the Revolution, the French monetary system collapsed, a monetary reform was inevitable. French gold and silver coins had disappeared to foreign countries or under the mattresses of the population; there was hardly any money left in circulation. To prevent the country from going bankrupt, the government created so-called assignats in 1789. The issuance of these paper banknotes plunged France into an inflation of an extent that had never been felt in Europe before. It was not until early 1796 that an end was put to the issuance of the by then completely valueless assignats.

France, First Republic. Consul. 5 francs year 8 (1799–1800). From Künker auction 190 (2011), lot 3313.

In August 1795, the Directory introduced a decimal currency – the silver franc of 100 centimes. The 1-franc piece was set to weigh 5 grams and have a silver content of 90 percent – this means that the new franc was to contain 4.5 grams of silver. However, at first only 5-franc pieces with a weight of 25 grams were minted.

Despite the new Republican coins, monetary circulation was dominated by old royalist coins for decades: the last pre-Revolution silver coins were cancelled in 1834, the copper coins of the kings were only replaced by Napoleon III in 1853.

The design of the depicted 5-franc piece shows the so-called Hercules group with the circumscription “UNION ET FORCE”. The group is dominated by Hercules, scantily clad in a lion’s skin, as the epitome of strength, protecting the female personifications of liberty and equality. Liberty holds a lance with a Phrygian cap on its tip; therefore, she does not only symbolise liberty but also how it was achieved – namely through violence. Equality holds two Freemason symbols in her hand – square and compasses; as Enlightenment thinkers, Freemasons were among the pioneers of liberal ideas. The square stands for righteousness, the compasses for fraternity and service to mankind. This design had originally been created for the 1- and 2-franc pieces, which were not minted after all due to a shortage of metal.

The Hercules group was used time and again as a coin image of the following republics – the Phrygian cap, however, was later replaced by a hand raised as to take an oath, symbolising loyalty to the republic.

France, First Republic. Bonaparte, First Consul. 40 francs year 12 (1803–1804). From Künker auction 350 (29 June 2021), lot 39.

In April 1803, the First Republic’s “statut monétaire” was enshrined in law by the “loi du 17 germinal an XI” (law of 17 April 1803 according to the Revolutionary Calendar). The franc – in 1803, 1-franc pieces were actually produced for the first time – was defined by the gold-silver ratio: pieces of 20 and 40 francs were created in gold with a weight of 6.45 and 12.9 grams respectively and a gold content of 90 percent. Thus, the ratio of gold to silver was set at 1:15.5, in line with the average value ratio of the two metals at the time.

France, First Republic. Bonaparte, First Consul. 1 franc year 12 (1803–1804). From Heritage Auctions 2014 April CICF Auction (2014), lot 24681.

In France, each and every one is permitted by law to bring gold and silver to a mint and have coins produced from it, only paying a fee for the minting cost. This is one of the achievements of the Republic – in monarchies, minting is considered a privilege of the ruler. Since France finally had a sound monetary system again, gold and silver – which had been hoarded during the years of instability – showed up again and flowed in large quantities into the mints. Therefore, significant numbers of the Franc Germinal, as it was called referring to its date of birth, were produced. Unlike its predecessors of the previous ten years, it no longer depicted the emblems of liberty and the Republic but a classical portrait of the First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte.

In the next part, you will find out about the proclamation of the Second French Empire as well as ancient models of French coinage.