The Bending Willow Tree

by Ursula Kampmann

On 29 January 2025, Künker is going to auction off a unique willow tree coin. The reverse of the 10-ducat piece depicts a willow tree in a storm. But what is the message that William V, the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel on whose behalf the coin was created, wanted to convey with this issue?

In 1627, Landgrave William V took over the rule of Hesse-Kassel. His father Moritz had cared for books more than for the economy and ended up ruining the country. The new landgrave was faced with a mountain of debt and that at a time when large parts of his territories were occupied by enemy troops. William saw himself confronted with a sheer abundance of problems, which he intended to solve one by one, not with violence but with reason and diplomacy.

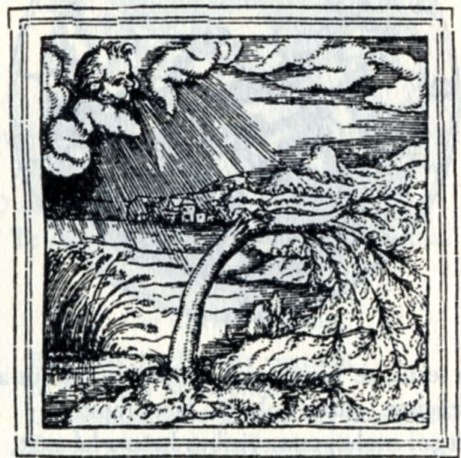

And it is precisely this situation that the emblem on the coin’s reverse describes, a willow tree bending with the wind in a storm. This illustration was very important to the landgrave of Hesse. It represents his take on the situation. We are dealing with an emblem here, a popular means of pictorially representing a personal mind-set in the early modern period.

Hesse-Kassel. William V, 1627-1637. 10 ducats, 1634, Kassel. Minted with the dies of the double taler. “Willow tree issue”. Probably the only specimen in private possession. Extremely fine. Estimate: 75,000 euros. From Künker auction 418 (2024), No. 64.

William V wanted to spread his message among as many people as possible. That is why willow tree issues were produced in many different denominations: as talers, multiple talers, fractional pieces, as ducats, multiple ducats and guldens. The 10-ducat piece offered on 29 January 2025 by Künker in auction 418 had been unpublished until it was first cataloged for Künker’s auction 279 on 23 June 2016. By now this gold coin has been added to the “Friedberg”, but it is still the only known specimen in private hands.

What Is an Emblem?

In the early modern period, an emblem was a sort of picture puzzle that could only be solved with the necessary educational background. While motto and image always belonged with interpretive verses, in most cases there was no room for the verses so that the observer needed all of his knowledge to interpret the depiction.

An educated contemporary of William would have been immediately reminded of an emblem entitled “Better bend than break” that had been published in a book by Adrian de Jonge in 1565. The illustration shows a broken tree while the slight reed next to it successfully resists the wind by bending with it. The accompanying explanation in Latin reads, in translation: “The mighty Boreas in a terrible storm overthrows the oaks trying to withstand him; but the reed stands unmoved and unbroken, despising him. He who is patient wins by evading him who is angry.”

William had not simply copied the emblem but adapted it to his purposes. After all, he did not want to be associated with reed because, in the Old and New Testaments, this plant symbolized apostasy. For a devout Calvinist, this was an absolute no-no. So William needed another plant with positive connotations that could bend with the wind. In the 17th century, the willow tree was the obvious choice.

.

At the beginning of the early modern period, the willow was a common crop tree whose trunk produced new rods every year. In a world without plastic and affordable rope, these rods played an important role. Willow rods were used to weave baskets, built fences and tie plants to poles. Wickerwork was even used as scaffolding in timber frame constructions. The fertile and versatile willow was therefore a plant with which the Calvinist was happy to associate himself.

William V not only replaced the tree, but also enriched the image with a reference to God, whose name appears in the sun. He thus placed himself under God’s protection and emphasized this with the new (Latin) motto: God willing, my humble self will be elevated by him. William V thus presented himself as a believing Calvinist, hoping that by God’s grace he would be given the strength to bend and thus overcome adversity.

It has sometimes been claimed that the die cutter did not know much about palms and created a willow instead of a palm tree. Nothing could be further from the truth. Every artist had his lexicons and his pattern books that were consulted when designing a new coin motif. And that was only if the educated client had not already done the work for him. Coin motifs were a matter for the top authority. For the sovereign, they were a means of displaying education. And William V was highly educated. He was a member of the Fruitbearing Society, the first German society of scholars, modelled on the Italian example and counting numerous aristocrats among its ranks.

If we needed to prove that early modern artists were well capable of depicting palm trees, it would be enough to take a look at the escutcheon of the Fruitbearing Society. By the way, it is yet another emblem. Its motto is: “Alles zu Nutzen” (to use everything). The depicted coconut palm is still known today for the fact that you can use all of its parts. The accompanying verses, which can be found in other sources, read (in translation): “The name fruitbearing so that each and every one, who joins our ranks or intends to do so, try his very best, … to bear fruit.”

When studying early modern coins, we have to re-learn a language that we are no longer familiar with. We have to rediscover the artful language of emblems. Fortunately the dictionaries of this language have been preserved for us and are easily accessible in new editions with comprehensive indices. It is worth browsing them to understand and interpret pictures that an educated person in the early modern period could easily decipher.