Bohemia and the House of Habsburg – a conflict-laden relationship

In early modern times, there were two diametrically opposed ways to determine a ruler: by inheritance or by election. This is rooted in two fundamentally different concepts of power. Whoever inherits his power will think of his territories as his personal possession. Whoever relies on his subjects in an election has to negotiate compromises on a regular basis. The German king was in this awkward situation. He was never to assume such an absolute power in a way comparable to his English or French colleague. And the Bohemian king was elected as well – until the Thirty Years’ War.

Ferdinand I. Ducat 1547, Prague. Künker 285 (2017), 218. Estimate: 15,000 euros.

The first Habsburg member elected king by the Bohemians in 1526 was Ferdinand I, younger brother of Charles V. He was the brother-in-law (and thus heir) of the former Bohemian ruler Louis. It was a well-considered election on the part of the Bohemians. The Habsburg could protect them against the advancing Turks. Additionally, they demanded religious tolerance for all citizens living in Bohemia and the related domains of Moravia and Silesia.

Ferdinand granted this tolerance and nevertheless expressed his Catholic conviction in his coinage. This ducat was struck in Prague in 1547. On its obverse, it features the Bohemian lion in the typical way, with its coiling double tail forming the number 8. On the reverse, Saint Wenceslas is shown, wearing full armor and the princely hat.

Wenceslas dining with guests, facing his brother and murderer Boleslav. Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, Guelf. 11.2 Augusteus 4, fol. 20v.

From the 13th century onwards, Wenceslas was patron saint of Bohemia but had lost much of his glamour after Luther’s criticism of the veneration of saints. To depict him was a statement of Ferdinand, also and above all in 1547, the year this ducat was minted. The Bohemians took advantage of the turmoil in the German Empire to attempt a rebellion of their own. This rebellion, however, failed when Charles V defeated the army of the Schmalkadic League in the Battle of Mühlberg. A victor, Ferdinand returned to Bohemia and forced his subjects to acknowledge the Habsburgs’ claim to the crown by inheritance. The ultimate victory for the House of Habsburg? Not at all.

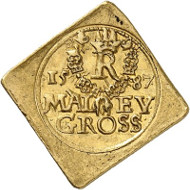

Rudolf II. Double dukatenklippe 1587. Gold trial strike from the dies of the Maley groschen-klippe. Künker 285 (2017), 221. Estimate: 15.000 euros.

Ferdinand was succeeded by Maximilian, whom the Bohemians liked very much for his Protestant tendencies. Maximilian was followed up by Rudolf who, in 1583, decided to move his residence to Prague.

This 1587 klippe of a two ducats’ weight is a gold trial strike of one of the most famous Bohemian coins, the Maley groschen. It is the first and only Bohemian coin with a Czech inscription. Maley gross means small groschen. The people also referred to it as sedmák = piece of seven because it equaled seven hellers. Its obverse features the Bohemian lion, the reverse the ruler’s monogram in the chain of the Order of the Golden Fleece.

Rudolf II as Vertumnus, oil painting by Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Skokloster Castle.

Among the entourage of Rudolf were not only alchemists and astrologers but the Papal nuncio and the Spanish ambassador as well. They urged the emperor to act in the spirit of the Counterreformation and to withdraw Ferdinand I’s Edict of Tolerance.

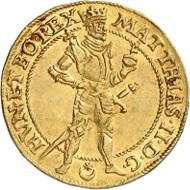

Rudolf II. Ducat 1593, Prague. Künker 285 (2017), 224. Estimate: 4,000 euros.

On 24 August 1599 – a day programmatically chosen since on that date, during the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre hundreds of Protestants had lost their lives once – Rudolf actually staffed all important offices in the Bohemian government with devoted Catholics. The cruel conversion of the people of Troppau made it clear to the Protestant estates that they would no longer be able to exercise their religion freely if Rudolf remained in power. But there was an alternative.

Rudolf II handing over his crown to Matthias, a view of Prague in the background.

Rudolf had not married. There was no legitimate heir. His younger brother Archduke Mathias took advantage of this to troop up a strong opposition and challenge Rudolf for his office during livetime.

The estates of Moravia decided in favor of him. They relieved Rudolf of his office and appointed Mathias the new margrave. That was something of a surprise because the Bohemian king, until that day, used to be Moravian margrave as well. In 1608, Mathias and his army invaded Bohemia and would have used force to unseat Rudolf would the latter have not contractually guaranteed Mathias the crown after his death. The estates of Bohemia served as guarantors and, as a reward, had Mathias confirmed absolute freedom of religion.

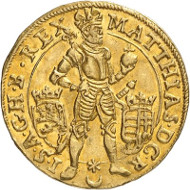

Mathias. Ducat no date, Prague. Künker 285 (2017), 225. Estimate: 7,500 euros.

Rudolf of course tried to remain in office. From his nephew, the Bishop of Passau, he borrowed 12,000 soldiers who laid siege upon Prague around the turn of the year 1610/11. The Bohemian estates didn’t put up with that. In April 1611, they unseated Rudolf and made his brother Mathias King of Bohemia.

Mathias. Ducat 1618, Prague. Künker 285 (2017), 230. Estimate: 4,000 euros.

It was bound to happen. The moment Mathias came into power he spurred the Counterreformation. But when the then 60 year-old established his cousin Ferdinand II as successor, he overdid things. Ferdinand was notorious for the cruelty with which he had recatholicized the inhabitants of Carinthia. The people in Bohemia knew what to expect from him and so the Prague Defenestration occurred in 1618, the year this ducat was struck in Prague, which then triggered the Thirty Years’ War.

This is not the place to recall what happened next. It’s common knowledge. The Bohemian estates once again tried to assert their right to vote. Again it became clear that the Habsburgs were militarily superior to such an extent that resistance was futile. The emperor won, the Empire lost. And Bohemia became the possession of the Habsburgs who used its revenues to fund the imperial policy.

Ferdinand III. 5 ducats 1641, Prague. Künker 285 (2017), 238. Estimate: 20,000 euros.

Manufactured in large numbers to be given as donatives, the large gold strikings illustrate how the Habsburgs exploited their “hereditary” lands to keep the Holy Roman Empire’s powerful parties well-disposed.

You can read a comprehensive auction preview in CoinsWeekly.