Money of the German Colonies

In 1871, after the great victory over France and the unification of the German Confederation in the German Empire, ambitious German businessmen thought that everything was possible. They saw their English colleagues earning the earth in the colonies and wanted to do just the same. In 1882, the “Deutscher Kolonialverein” (“German Colonial Association”) was established, in 1884 the “Gesellschaft für Deutsche Kolonisation” (“Society for German Colonization”). Therewith the dream of the exotic faraway place was distributed even to the most remote area in Germany.

Chancellor of the German Empire Otto von Bismarck was rather skeptical about the colonial adventure. The possible yields did not seem enough to justify the high costs. But even Bismarck could not fight back the colonialmania of the German population. Perhaps he even liked the idea of getting rid of – socialistic – elements causing turmoil by a possible emigration to the colonies.

In any case, in April 1884 the Lüderitzbucht (Angra Pequena) that had been acquired by a merchant from Bremen was claimed a German protectorate, followed by Togoland in July and some possessions in Cameroon. In February 1885, the most important acquisition – from the numismatic viewpoint – was made, the East Africa territories that had been acquired by Carl Peters. In May, the Pacific territories followed, North New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago.

According to plan the government should only sparsely interfere in those territories. Administration ought to be left to private organizations, which would be granted extensive trade privileges in return. But this remained wishful thinking since the situation was precarious pertaining yields. One by one, the territories were mandated to the German Empire that, in turn, bore all costs.

German East Africa

A good example for that is German East Africa that had been acquired by the German East Africa Company in winter 1884/5. The Sultan of Zanzibar, who was interested in this coastal district himself, addressed a protest note to the German government that was forced to dispatch a naval squadron to protect the subjects’ private property – that squadron broke resistance with military force.

General map of Africa, as of 1887 – shown is the territory after the German-British agreement of 1886 and prior to the division of the Zanzibari mainland possession 1888. From a Brockhaus edition of 1887.

A treaty was negotiated that, immediately after it was signed, prompted a revolt of the coastal Arabian-oriented population. Again, the German government had to send in troops to secure the colony. This led to East Africa being officially mandated to the German Empire as early as 1891. State and private administration coexisted – not always causing satisfaction to everybody.

But where to find green rubber and cotton plantation German petit bourgeois had dreamed of?

The local population did not seem too eager to abandon their own fields to increase the new masters’ profits. Although a highly developed monetary system was applied in the trade, the country’s economy was based on the self supply of smallest economical units.

Thus, an operating tax system was called for forcing the local people to earn money with their work to pay taxes.

German East Africa, 1 Pesa 1890, Cu. J. 710. Ritter, special list “Das Geld der Deutschen Kolonien”, no. 45513.

Of course, adequate coins were needed for trade. Already in 1890, a first emission of copper coins was issued in Berlin by order of the German East Africa Company. They were called Pesa and show on the obverse a laurel wreath and the Arabic legend “Company of Germany“. On its reverse the imperial eagle was depicted. An Indian Rupee, the most important coastal currency, equated 64 Pesa. Pesa were issued in high numbers (in 1892 alone, the emission’s last year, 27.541.389 were manufactured).

German East Africa, 1 Rupee 1892. Ar. J. 713. Ritter, special list “Das Geld der Deutschen Kolonien”, Nr. 45447.

The silver coins, emitted since 1891, were issued in considerably lower numbers. They show on the obverse the German Emperor and on the reverse the coat of arms of the German East Africa Company, a striding lion in front of a palm tree. The fractions were one quarter, one half, one, and a double Rupee thereby matching the local currency situation.

All those coins were made on behalf of the German East Africa Company that had the coins manufactured at its own expense in the Berlin Mint. This yielded a pretty penny.

Local businessmen were used for years to the Rupee’s heavy fluctuation. They utilized the basis that causes their business partners in far Germany trouble. The administrative officials, too, were unhappy with the situation. Their salaries were fixed in Mark whereas they received the payment in local currency. A basis of up to 20% within a year made the income unratable.

It comes as no surprise, then, that the German Reichstag dealt with the topic. In 1902, the trading company left the regulation of the monetary situation in the colony to the German government against a considerable compensation.

In cooperation with the British and the Sultan of Zanzibar the German Rupee was stabilized first; consequently, its value was fixed to 1 Rupee = 1.33 Mark. The new fraction was the Heller equaling 100 Rupees.

German East Africa, 1/4 Rupeee 1904. Ar. J. 720. Ritter, special list “Das Geld der Deutschen Kolonien”, no. 45516.

German East Africa, 1/2 Rupee 1904. Ar. J. 721. Ritter, special list “Das Geld der Deutschen Kolonien”, no. 45486.

German East Africa, 1 Rupee 1910, J. Ar. J. 722. Ritter, special list “Das Geld der Deutschen Kolonien”, no. 45457.

The silver Rupees continued to be minted without any significant change to the design. Only the legend changed to Deutsch Ostafrika (German East Africa).

German East Africa, 5 Heller 1909, J. Cu. J. 717. Ritter, special list “Das Geld der Deutschen Kolonien”, no. 45468.

The Heller from then on depicted a laurel wreath on one side, the imperial German crown on the other.

Until 1914, those coins were minted in Berlin and Hamburg. Then the First World War broke out. The supply ships faced an increasing number of problems to break the enemy lines.

Those problems notwithstanding, the government needed more and more money. After all, the soldiers had to be paid! The solution was a local mint that was based in Tabora. Tabora was the second largest city in German East Africa. Those responsible had moved the colony’s administration from the exposed Dar es Salam there.

German East Africa, 15 Rupees 1916, Tabora. Au. J. 728a. Ritter, special list “Das Geld der Deutschen Kolonien”, no. 45670.

For the parties involved minting was a special experience. Nobody had any previous knowledge. Dr Schumacher, a mining engineer, recounted on his appointment at the beginning of 1916: “When I reported to the Governor he asked me whether I could produce coins. I answered that I knew some things about gold mining but had no understanding of coin minting.” He pointed at the large encyclopedia above his desk and said: “We need gold coins to pay our men. We do not have any silver but gold – we have plenty of. In that encyclopedia you will find everything you need!”

German East Africa, 20 Heller 1916, Tabora. Me. J. 724b. Ritter, special list “Das Geld der Deutschen Kolonien”, no. 45713.

Local goldsmiths made the dies – the tools for the gold 15 Rupees pieces were delivered by a Singhalese worker who, according to Schumacher, was doing his job most thoroughly when being drunk.

The Belgian occupation of Tabora put an end to the minting the same way as the Treaty of Versailles sealed the fate of the colony German East Africa. It was divided between Belgium and Great Britain.

German New Guinea

More manageable are the coinages of German New Guinea that was in German control since May 1895.

Adolph von Hansemann. Wikipedia.

That colony was initiated by banker Adolph von Hansemann. As founder and owner of the biggest private bank of the German Empire he ensured a controlled financing during the Franco-Prussian War 1870/1 and could count on the government’s sympathy for his entrepreneurial activities. He funded railway tracks in Venezuela and Shandong, established the German Sea Trading Company and the German New Guinea Company.

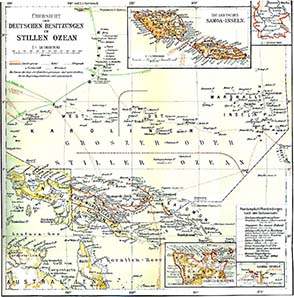

Overview of the German possessions in the Pacific Ocean. Brockhaus 1920 / Wikipedia.

In May 1885, the sovereign rights of the so-called Kaiser-Wilhelmsland and the Bismarck Archipelago were conferred to the latter with an imperial writ of protection. Only foreign affairs were left to the German government.

The island’s new masters wanted quickly to get an extensive plantation economy up and running. But they lacked good transport facilities and trained workers. On top of that, the company’s management with the head in Berlin was too distant from the on-site situation to find any solutions. In short, the investors had miscalculated. The German New Guinea Company was forced to sell their colony rights for impending bankruptcy to the German imperial government in 1898.

German New Guinea. 10 Pfennig 1894, A. Cu. J. 703. Ritter, special list “Das Geld der Deutschen Kolonien”, no. 45537.

A reminder of that episode of German economic history is the splendid coinage that was made solely in 1894 on behalf of the German New Guinea Company in Berlin. Famous is the beautiful depiction of two birds of paradise, a design created by Otto Schultz, at this time, the most gifted die cutter of the Berlin Mint. The birds are shown on all denominations, from the 10 Pfennig piece made of base metal to the gold 20 Mark piece.

German New Guinea. 2 Pfennig 1894, A. Cu. J. 702. Ritter, special list “Das Geld der Deutschen Kolonien”, no. 45535.

Only for the 1 and the 2 Pfennig piece a simpler design was created with the company’s name and two palm branches on the obverse.

The coins were introduced to gain control of the disappearance of German circulation coinage. As long as foreign coins were accepted as currency in German New Guinea the few coins that Berlin had sent to the colony set back home. It was for that reason that special coinages were introduced in New Guinea in 1894 which were forbidden to export. At the same time, foreign currencies were prohibited. German coins were allowed to coexist with the New Guinea Mark.

At that point, nobody really expected the colony’s economic breakthrough anymore. In 1888, during a volcanic eruption, an island sank, and the subsequent tsunami claimed the lives of 5,000 people. The colony’s capital had to be abandoned in 1891 due to a malaria epidemic. Shortly before the First World War commenced only 772 Germans lived in the colony, according to the one and only census ever conducted. It comes as no surprise that Australian and Japanese troops were able to conquer German New Guinea immediately after the war had started without meeting any resistance.

Kiao-Chau

A third German colony has left numismatic traces: Kiao-Chau, a German harbor in the middle of China. Expectations had been running high since China promised to become a vast outlet. Apart from that, German colonial policy, being quite expensive, needed a fresh poster child. Hence, Kiao-Chau was designed a model colony right from the beginning aiming to show the Chinese, the skeptical Germans and the rest of the world what enormous advantages came for everybody with such a colony.

Kiao-Chau Bay. Wikipedia.

Famous military officers such as Freiherr Ferdinand von Richthofen or Admiral Tirpitz had recommended Kiao-Chau Bay to become a port. In 1897 two Steyler Missionaries were murdered in China. This incident was taken as an excuse to occupy the coveted bay. The German marine secured the area, before the Chinese government was informed about the assassination. It was only a matter of negotiations that China leased the bay to the Germans in 1898 for 99 years.

The administration was assumed not by the German Colonial Office but the Reichsmarineamt. Under the latter’s control, the port became a well connected center of economy and culture. There was a 14-day mail steamer connection to Shanghai, a connection to the Trans-Siberian Railway, the famous Tsingtao Brewery, a university – in short, there was nothing that could not be built.

Kiao-Chau. 5 Cent 1909. Cu-Ni. J. 729. Ritter, special list “Das Geld der Deutschen Kolonien”, no. 45531.

Kiao-Chau naturally had its own coins, but they were only marginally important in daily monetary circulation – 5 and 10 Cent – showing Chinese characters on the obverse. The characters in the middle of the border of dots meant “Kaiserliche Deutsche Münze” (“German Imperial Mint”), above “Tsingtao“ and „5” and “10 Cent”, respectively.

Kiao-Chau. 10 Cent 1909. Cu-Ni. J. 730. Ritter, special list “Das Geld der Deutschen Kolonien”, no. 45530.

The more extensive legend below meant “20” and “10”, respectively, „piece on a dollar big money“ meaning that a Mexican dollar as the most prevalent trading currency in China equates 100 Cent. The legend speaks of “big money” since it was silver money stable of value that Chinese language differentiated from the intrinsically valueless bronze money, the cash-coins.

The pieces’ reverse shows the German marine eagle, the imperial eagle on an anchor. After all the marine made up the administration.

Even though a number of pieces with reference to the year 1909 are preserved, they were not all manufactured then but over a period of many years. It soon turned out that the acquisition of Kiao-Chau was by no means an economic success. The German state had invested roughly 100 million Reichsmark. The yields made up not even a tenth.

The marine nevertheless defended the port against Japanese and British war ships in a bloody war that extended over months. In November 1914, Germany surrendered. The former German colony was mandated to Japanese administration before it was given back to China after massive protests.

The defeat in the First World War had put an end to the ambitious colonial policy of the German Empire. The exotic territories most possibly were mourned only by few since Germany had its own severe problems due to the depression. In retrospective one might say that Germany had saved itself many problems with the “expropriation” of the “appropriated” territories former colonial powers like France and England have to grapple with up to the present day.

We thank Münzhandlung Ritter / Düsseldorf for providing us with photographs from their current special list “Das Geld der Deutschen Kolonien” (“Money of the German Colonies“)