Bullion coins part 7: The ducat

translated by Christina Schlögl

You can still purchase re-strikes of 1 ducats and 4 ducats at the Austrian Mint with the year marked 1915 as bullion coins, despite the fact that this denomination was officially discontinued as legal tender on Austrian national territory in 1858.

1 ducat with the date 1915. Photo: Austrian Mint.

Trading coins

The Vienna Monetary Treaty, which had enabled Austria to become attached to the German economic and currency system, had abolished pistols and ducats and the crown had been introduced as common currency. Nevertheless, people wanted to keep using ducats as trading coins, because they were well established and accepted on the international market, especially in Africa, the Levant and Asia. Consequently, a constant supply was needed and the mint delivered it upon imperial order.

The 4 ducat with the year 1915. Photo: Austrian Mint.

People particularly liked using the 4 ducat as a decorative part of their traditional attire. Its diameter measured 39.50 mm. This was a lot compared to its weight of 13.96 g.

The 4 ducat with Franz Joseph’s portrait was used for elaborate parts of traditional garments in Dalmatia, Bosnia, Serbia, Bulgaria and Greece. Photo: Aleksandar N. Brzic, Four Ducats Coins of Franz Joseph I (1848-1916) of Austria: Their use in Jewellery and some hithero unpublished imitations. In: FS Glasgow 2011, p. 1697.

Thus this 4 ducat seemed especially representative when it was sewn onto bonnets or worn on long necklaces.

The financial burdens of World War I lead to a preliminary end of gold minting. But it was as early as 1920-1936 that the minting of ducats was taken up again, and it has been going on until this day, starting again in 1950.

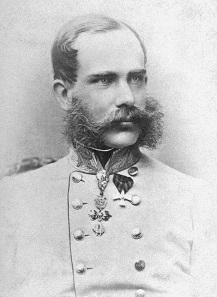

Emperor Franz Joseph at the age of 35, 1865.

Emperor Franz Joseph (1830-1916)

The obverse of the ducats shows Emperor Franz Joseph I, ruler of the Habsburg empire from 1848 to 1916.

Franz Joseph Karl von Habsburg, whom most German audiences have come to know from Karlheinz Böhm’s rendition of him in the “Sissi” movies, was born on 18 August 1830 as the youngest son of Emperor Franz I. He was barely 18 years old when he came to the throne. He followed his uncle, Ferdinand I, who had been forced to refuse his office in the March Revolution in 1848. Franz Joseph was the adolescent bearer of hope for the progressive middle class. They expected him to ease censorship and enforce more institutional rights. But the new emperor had been raised in the spirit of the Restoration. The new constitution he forcibly signed on 4 March 1849 was never fully implemented and it was repealed only three years later.

Votive church. Postcard, date stamp 15 April 1908.

As a consequence, Franz Joseph was anything but popular during his first years of ruling. The votive church in Vienna still gives evidence of this. It had been built to thank God for saving the emperor during an attack in the year 1853.

Only one year later, on 24 April 1854, Franz Joseph married “his” Sisi, a real love marriage, even though she did not necessarily make it easier for the emperor to rule his country. Elisabeth fought back against the rigid Habsburg monarchy and flirted with liberal ideas. She earned her husband some sympathy but soon retreated from court life and traveled through Europe instead.

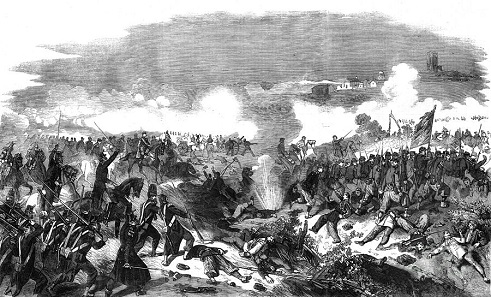

The battle of Solferino, with many people wounded, became a crucial experience for many peace activists. Henri Dunant, founder of the Red Cross, was one of them. Contemporary copper engraving from a British newspaper.

The devastating defeat at Solferino of the Habsburg reign by the French in Northern Italy and the victory of Prussia during the Austro-Prussian War 1866 forced Franz Joseph to react to the liberal and national ideas of his empire’s multicultural population. He agreed to political reforms and – being crowned king of Hungary in 1867 – founded the Dual Monarchy. But this did not suffice. Franz Joseph’s inability to combine and unite the interests of the different demographic groups resulted in numerous independence movements, the Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and World War I.

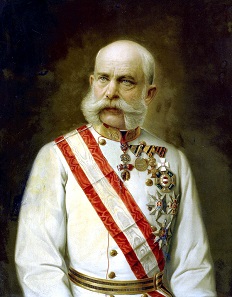

Portrait of Franz Joseph, ca. 1910. Oil painting of an anonymous artist. Bundesmobilienverwaltung.

His long reign – Franz Joseph ruled for 68 years, making it one of the longest reigns in all of history – made the old emperor a living symbol of a “good old” past. Thus the Austrians associated his reign with the splendour of the Ringstraße, with economic prosperity and cultural meaning, even before his death. After all, around 1900 the metropolis Vienna was the centre of the intellectual elite. It’s where Jugendstil with artists like Klimt, Kokoschka or Schiele came to existence. Gustav Mahler and Arnold Schönberg were revolutionising music, Otto Wagner and Adolf Loos were doing the same with architecture. And let’s not forget psychoanalysis, which inspired numerous writers like Arthur Schnitzler, Joseph Roth or Robert Musil. Whether or not the emperor was responsible for these developments (or deeply despised them) shall remain at anyone’s guess.

Franz Joseph I died a year after the minting of ducats with his portrait had been discontinued, at the age of 86 in the middle of World War I on 21 November 1916. Two years later, the Habsburg monarchy was history.

The “Medium common Coat of Arms”. Source: Wikipedia / Sodacan. CC-BY 3.0.

The coat of arms

The reverse depicts the so-called “Medium common Coat of Arms”. It is the coat of arms that was used between 1866 and 1915, which shows the crowned Habsburg double eagle, created after the Byzantine model. One head is facing westward, the other one eastward. It has a shield on his breast, depicting the domestic coat of arms of the ruling House of Habsburg-Lorraine. It is composed of three elements: The left crest (heraldic right) represents the Habsburg family, the middle crest stands for Austria and the right one (heraldic left) for Lorraine. The coat of arms is framed by the collar of the Order of the Golden Fleece.

The inscription

In translation, the inscription reads Franz Joseph I, by the grace of God, Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, Bohemia, Galicia, Lodomeria (= Volhynia), Illyria, Archduke of Austria.

The original ducats: Venice. Andreas Dandolo, 1342-1354. Ducat n.y. From Gorny & Mosch sale 205 (2012), No. 4160.

Denomination

The ducat might well be one of the most long-lived coin types in history. It originated in Venice in the year 1284. Its inscription, which ended in the word DVCATVS, gave the ducat its name. These Venetian coins circulated all over Europe and inspired many other mints. Since 1527, the ducat was the only gold coin minted in the Habsburg territories. The Reichsmünzordnung (Imperial Minting Ordinance) of 1559 made it one of the most important gold coins of the Holy Roman Empire. This tradition, which lasted almost half a century, has stayed alive due to Austrian re-strikes until this day.

Numismatic data of the ducat

Coin description:

Obverse: FRANC IOS I D G AVSTRIAE IMPERATOR

Head of Emperor Franz Joseph in imperial vestment with laurel wreath f.r. (for 4 ducats)

Head of Emperor Franz Joseph with laurel wreath f.r. (for ducat)

Reverse: LOD ILL REX A A 1915 – HVNGAR BOHEM GAL

Crowned imperial-royal double eagle with shield, holding imperial sword and orb in its claws.

4 ducats / 986 / 13.9636 g (13.7696 g) / 39.9 mm / 0.8 mm

1 ducat / 986 / 1.4909 g (1.4424 g) / 19.75 mm / 0.8 mm

You can find all articles of our survey of bullion coins here.