From Lira to Euro. Italy’s History in Coins – Part 3: The Battle for Rome

The Kingdom of Italy was an unfinished state. The project of unifying the entire people of Italy in a single country was not completed yet – there were still “terre irredente”, the “unredeemed territories”. These areas were located outside the Italian borders although Italian was the mother tongue of the inhabitants: Rome and Veneto, but also Trieste and Tyrol.

This painting from 1853 impressively shows what it meant when Pope Pius IX passed through the Arch of Titus in his magnificent chariot. This pope did not simply renounce his claim to secular power because there was an Italian state claiming his territories.

The Battle Between Church and Country

The fact that Rome – the heart of Italy! – was not part of the Italian state was a thorn in the side of patriotically minded people. For Pope Pius IX (1846-1878), renouncing to his claim to secular power was not an option. In 1864 he proclaimed the 80 major errors of his age in his “Syllabus errorum” and banned all achievements of modern thought – from the freedom of conscience and of the press to civil marriage. Since Victor Emmanuel II claimed to be king of all Italy – i.e. including the Papal States – the Pope excommunicated him without further ado. And in his decree “Non expedit”, the Pope prohibited Italian Catholics from participating in political elections – a ban that was only partially lifted by Pope Pius X (1903-1914).

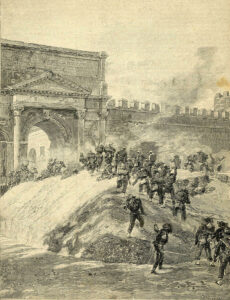

“Breccia di Porta Pia”, i.e. the moment the troops broke through the Porta Pia of Rome’s historic city walls, marks a turning point in the city’s history. On 20 September 1870, the troops of the young state of Italy captured their future capital, ending papal rule over the Eternal City. Xylograph of 1890.

The Capture of Rome

In the fall of 1870, the Papal States fell victim to higher European politics: France, the protector of the Pope, declared war against Germany and suffered a crushing defeat near Sedan. Emperor Napoleon III was taken prisoner by Prussia. Prussia besieged Paris and France withdrew its troops from Rome. This cleared the way to the Eternal City: it did not take long for Italian troops to conquer Rome and to proclaim it the capital of Italy.

After losing Rome, Pope Pius IX was kept as a prisoner in the Vatican and rejected any sort of compromise. He did not make peace with the new state of Italy until his death in 1878; neither did his successor Leo XIII.

That was the end of the secular power of the Pope, which had begun in 754 with the Carolingian King Pippin (751-768) giving territories to the Pope: as of September 1870, Pope Pius IX was the ruler of a tiny territory around St Peter’s. The days of the extensive Papal States were over. The Pope was to enjoy all honorary rights of a souverain, remain in possession of the Apostolic Palaces and his summer residence and receive an annual pension of over 3 million lire. But Pius rejected the offer; he considered himself a “prisoner in the Vatican” and did not leave it ever again. When the coffin with the Pope’s body was transferred from the Vatican to the Basilica of San Lorenzo three years after his death, Italian patriots threw stones at it.

Papal Money: From Scudo to Lira

We have to keep in mind that the Papal States are an actual state, with its own money. Italian unification also had an impact on this currency. At first, the “scudo romano” circulated, coins that were first minted in the mid-16th century. In the following 250 years or so, Popes minted scudi with a variety of magnificent images. The obverse of Vatican coins usually featured the image of the Pope; the reverse was used for propaganda – for religious or secular purposes or to illustrate papal politics.

This half scudo was made on behalf of Pope Clement XI (1700-1721), who was a great builder. On this coin, he shows the port of Ripetta, which was built on his behalf, with the churches of San Rocco on the left and San Girolamo degli Schiavoni in the centre. In the foreground, we can see the Tiber with five boats. By the way, the building material for the new harbour came from the Colosseum, which partially collapsed during an earthquake in 1703. The small Ripetta port no longer exists today; it fell victim to a Tiber regulation in the 19th century.

In 1835, the Papal States made a step towards the French monetary system: Pope Gregory XVI (1831-1846) adopted a law according to which a scudo equalled to 5.38 lire of the French weight standard and was divided into 100 bajocci of 5 quattrini each.

A good 30 years later – in June 1866 – the Papal States adopted the lira and introduced the decimal system: from then on, one lira of the French weight standard equalled to 20 soldi or 100 centesimi.

In the next episode, Italy establishes itself as a colonial newcomer, creating new currencies in Eritrea and Somaliland.

Here you can find all parts of the series “From Lira to Euro. Italy’s History in Coins”.

If you are interested in Vatican coins and medals, you should certainly read this book review.