Catherine the Great, Moscow and the Kremlin

When listing Catherine’s great building projects, the famous Catherine Palace in Pushkin or the Chinese Palace in Lomonosov (former Oranienbaum) come to mind first. For Grigory Orlov, the empress built the Marble Palace in Saint Petersburg, for Potemkin the Tauride Palace, and for her son Paul the palace in Pavlovsk. All these buildings had one thing in common: They were not located in Moscow, but in and around Saint Petersburg.

The young Catherine II at the age of approx. 16 years. Painting by Georg Christoph Grooth.

For Moscow was not among Catherine’s favorite places to be. It reminded her of her arrival in Russia, when she was summoned from her home in Stettin at the age of a mere 16 years in order to check if she was in fact a suitable wife for the tsarevich. Her marriage was not yet a done deal; first, little Sophie – which was Catherine’s name at the time – had to convert from Lutheranism to Orthodoxy: a decision of conscience that was not easy on her and brought on an existential crisis which she tried to evade by falling sick.

Today, we would probably call it psychosomatic; back then, the courtiers started talking that Sophie had tuberculosis and was in no way a possible bride for Peter III. For weeks, Catherine was hovering between life and death, while her mother stayed away from the sickbed. Johanna of Anhalt-Zerbst could not bear the sight of blood, and the weakened girl underwent bloodletting up to 16 times a day.

Moscow at the end of the 16th century. Watercolor by Apollinary Vasnetsov.

Eventually, Catherine recovered, opted for the orthodox baptism and married Peter III; nevertheless, she had had enough of Moscow. Precisely eight times did she visit the city she called “City of Deadlock” during her entire reign of 34 years. For Catherine, Moscow was a metropolis under Asian influence, where she believed to feel Mongolian influence. There were no signs of enlightenment there, only darkest superstitions, as Catherine wrote: “Never can a nation have been confronted by more objects of fanaticism, by more miracle-working images at every turn, more churches, more clergymen, more monasteries, more believers, more beggars, more thieves…” Compared to Moscow, which she liked to call it “Isfahan”, after the capital of the Persian Shah, Saint Petersburg appeared to her like paradise.

Coronation of Catherine II. Painting by Stefano Torelli.

And still: Moscow was the heart of Russia, the old city of the tsars. Catherine could not ignore it if she wanted to win the love of her Russian subjects. After all, Peter III was so unpopular mainly because he wanted to restructure Russia based on the model of Prussia. Conversely, Catherine had to show that she was more Russian than the Russians themselves. Thus, she ostentatiously moved to Moscow for the coronation on 22 September 1762 and lived very uncomfortably in the at the time heavily destroyed Kremlin, in order to be crowned as Empress of Russia in the Trinity Cathedral according to ancient customs.

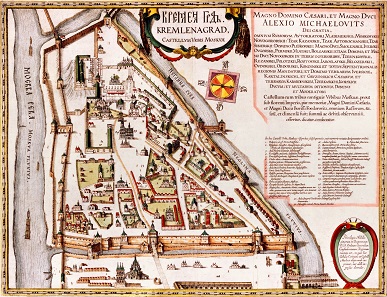

Plan of the old Kremlin around 1600.

Resurrecting the center of the old Russia in renewed splendor must have seemed the ideal project for Catherine to express her Russian conviction. Thus, she made her first plans for the restructuring of the Kremlin shortly after her coronation. As responsible architect, she appointed Vasily Ivanovich Bazhenov, a Moscow citizen who had studied abroad and was to become the most important neoclassical Russian architect.

Draft for the rebuilding of the Kremlin by Bazhenov.

His first draft is dated 1767. His latest model, which was supposed to be the basis for the restructuring, would have turned the Kremlin into the largest neoclassical complex in all of Europe. Only the three cathedrals would have remained intact.

The demolition work had already begun, when in 1771 the plague broke out in Moscow and an angry mob attacked the Kremlin. Bazhenov himself is said to have stood protectively in front of his model palace, which by then had cost about 60,000 rubles.

Catherine II. Gold medal by T. Ivanov on the occasion of the building of the new Kremlin Palace. Probably struck later-on with the original dies of the 18th century. Very rare. Extremely fine to FDC. Estimate: 80,000 euros.

It was that very model which was transferred to Saint Petersburg on 120 sledges in 1772. Catherine looked it over, gave permission and on 1 June 1773, the cornerstone ceremony was held. The latter is commemorated by the very rare gold medal offered at Künker’s. It shows the building, which at the time was still in planning and only existed as a model, already fully completed.

Catherine paid for 20 buckets of vodka and 40 buckets of beer, which were distributed among the builders on the occasion. The empress herself, however, did not attend the ceremony, because resistance was growing against the irreverent demolition of the Kreml. Even the loyal poet of the court, Gavriil Derzhavin, condemned Catherine’s handling of the Russian past, and on top of that, cracks began to show in the walls of the Cathedral of the Archangel, which housed the graves of almost all Russian tsars before Peter the Great.

As a consequence, Catherine the Great had the construction works stopped immediately. She claimed the geological conditions did not allow for buildings this size. The real reason may well have been a different one: Catherine was not willing to finance a project in a city she despised, which, due to the architect’s megalomania, was bound to become a bottomless pit. For Bazhenov was already talking about building three giant avenues leading from the Kremlin through Moscow, in order to modernize the entire city.

All that never came to be executed. Instead, when she returned to Moscow in 1775, Catherine lived modestly and comfortably not in the Kremlin, but in three spacious houses provided by the Golitsyn and Dolgorukov families.

Here you can read a comprehensive auction preview of sale 306 in which this medal will be offered.