Prussian Spirit in Tsarist Russia

He was not meant to sit on the Russian throne for a long period, that young man from the house of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp, who ascended the throne of his grandfather Peter I under the name of Peter III on January 5, 1762, which was December 25, 1761, according to the Russian calendar. If we believe in the rather biased tradition passed down during the 34 years of the reign of his wife and usurper of the throne, Peter III felt not like a Russian. He was a keen admirer of Frederick II of Prussia whom he used to imitate in many details.

After having lost both his father and his mother at the age of eleven, 14 year-old Peter was sent from his hometown Kiel to Saint Petersburg in order to live, as heir to the throne, at the court of his aunt Elizabeth. One can only speculate how the boy might have felt in distant Russia. The fact is that he developed a lyrical fascination with Frederick II of Prussia with whom he corresponded on a regular basis.

The palace of Peter III in Oranienbaum. Photograph: Maryanna Nesina / https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

At his palace Oranienbaum the Russian prince built his own little realm modeled on Germany where the Prussian virtues were being held in high esteem: industry, obedience, integrity, austerity, diligence and sense of duty, and Peter III setting a shining example in all these virtues. As was to be expected, the Russian nobility was irritated. Not to forget that Russia had been at war with the ambitious King of Prussia since 1757. Against this background, Peter’s indiscriminating veneration of his idol surely was anything but a clever political move.

Coronation portrait of Peter III of Russia, by Lucas Conrad Pfandzelt, 1762.

The hardships of several years of war, during which the Russian troops had even occupied Berlin for a short period of time, counted for nothing when Peter III concluded peace with Frederick a few months after his accession to the throne. But was that the reason why Peter III was dethroned? His enemies talked of an aberration already apparent at a tender age. After her coup d’état, his wife Catherine wrote her memoirs, in which she went on about her life of suffering at her perverted husband’s side. As a matter of fact, Peter’s deeds shed a very different light on him: he immediately initiated a comprehensive reform program. He was following the example of an enlightened absolutism where even the Tsar had to bow to laws. With this in mind he abolished the Secret Chancellery, a secret police and at the same time secret court, which had to answer solely to the Tsar. Peter prohibited torture, abolished the antisocial salt tax and replaced it by a luxury tax that mainly affected the nobility. He prepared the disempowerment of the Orthodox Church and had worked out laws abolishing serfdom.

Peter III. Gold 10 roubel 1762, St. Petersburg. Auction Künker 264 (June 25, 2015), lot 4590; estimate: 75,000 euros.

Peter’s desire to imitate Prussia becomes apparent even in the imagery of his coins. His coiffure closely resembles the Prussian hairdo. He wears the unpretentious Prussian pigtail as it was worn by German soldiers. It stood in marked contrast to the lavish full-bottomed wigs that were still very much en vogue with his Russian contemporaries. Any antique-like garments are replaced by the plain chest armor which Peter has proudly embellished with the Prussian officer’s sash. A close inspection likewise reveals the metal gorget as another badge of Prussian officers.

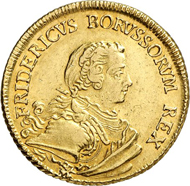

The great role model of Peter III: Frederick II on his Friedrichs d’or from 1749. Auction Künker 250 (2014), lot 2602; estimate: 5,000 euros. Hammer price: 17,000 euros.

In much the same attire Frederick the Great used to be portrayed on his early Friedrichs d’ors: the hair tied in a soldier’s tail, wearing the chest armor. What seems almost dainty with the model becomes the epitome of rigid discipline with the epigone.

The predecessor of Peter: Elizabeth I with a gold 10 roubel piece from 1756, struck in Moscow. Auction Künker 258 (2015), lot 851; estimate: 15,000 euros. Hammer price: 32,000 euros.

The reverse of the predecessor was adopted by Peter. The Russian double eagle is surrounded by the coat of arms of Moscow, Kazan, Siberia and Astrakhan.

Whatever the intentions of Peter III might have been, they were not the intentions of his wife Catherine. Her lover Grigory Grigoryevich Orlov staged a coup. As head of the guards regiment he was in the position to do so. Rumor at the court had it that the child which Catherine had given birth to only a couple of weeks before was in fact his, which was why Peter had planned to divorce her. And indeed, the young Tsar had written a letter to Frederick exactly about this situation, asking him for advice.

Catherine the Great in her Coronation Robe, by Vigilius Eriksen, 1778.

His thoughts and plans found almost no expression in the sources. It was his eloquent widow Catherine who passed down tradition. That is why, up to the present day, Peter III is still considered by some to have been a besotted muddlehead who, for the good of Russia, had to be dethroned.

His contemporaries thought different, as evidenced by the five revolts occurring in the aftermath of his death which Catherine crushed before her fame was being made public in the whole enlightened world by the French philosophers she had presented with gifts so generously.

If you are interested in the 10 rouble piece featured in this article, you can go directly to the Summer Auction Sale of Künker.

And we published a preview of this auction sale in CoinsWeekly too.