The People of Zurich and their Money 13: And lead us not into temptation!

by courtesy of MoneyMuseum

Our series takes you along for the ride as we explore the Zurich of times past. On October 1, 1869, bank director Karl Stadler, attended by procurator Heinrich von Wyss, opened the safe of the Union Bank of Switzerland in the Zurich branch. It was empty … Much like a good DVD, this conversation comes with a sort of “making of” – a little numismatic-historical backdrop to underscore and illustrate this conversation.

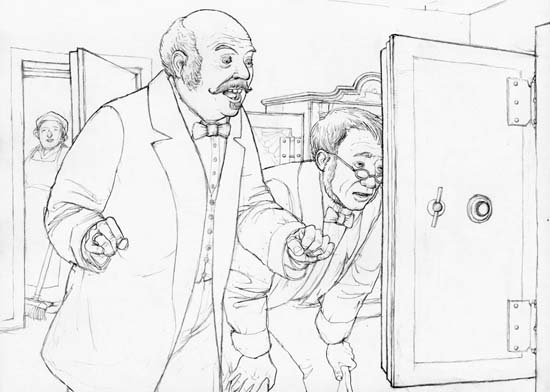

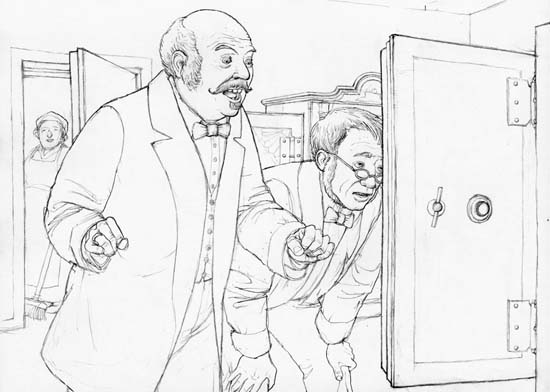

October 1st 1869. Bank director Karl Stadler opens the safe of the Zurich branch of the Eidgenössische Bank in the presence of confidential clerk Heinrich von Wyss. Drawn by Dani Pelagatti / Atelier bunterhund. Copyright MoneyMuseum Zurich.

Bank director: (thunderstruck) No!

Clerk: Good God! What shall we do now?

So it’s really true.

I never would think as much of Emil Schärr.

All our cash reserves are gone.

What will our shareholders say, and the central office in Bern?

But our bosses in Bern sent this Emil Schärr as watcher!

I can’t believe it. He was such a nice, respectable young man. How were we to know? He always was so polite. And he was the only one who really understood this new French accounting system. (break) Good God, director Stadler, do you think he escaped, because we planned our audit for today?

(toneless) I should have known better. They warned me. A bank director named Schärr was said to have lost enormous amounts by speculating in Geneva. And I did ask the young man yesterday, what about these rumours. Do you know, what he answered, Wyss? It must be a misunderstanding. And I believed him!

(toneless, too) You think, that’s not all, what’s missing? He embezzled more?

Much more, Wyss, much more. We are ruined!

Good God.

Wyss, we now have to inform the police. And then I’ll send a telegram to the management in Bern.

Switzerland. 20 franks 1871 B. Pattern. From auction sale Münzen & Medaillen Deutschland GmbH 22 (2007) 1751.

Making of:

When bank director Karl Stadler and his procurator Heinrich von Wyss opened the vault of the Union Bank of Switzerland in the morning of October 1, 1869, all cash reserves were gone. According to the statement of the cleaner, the cashier Emil Schärr had taken it. He had escaped with 41,000 franks cash because he feared that his defalcations would be discovered. Thanks to the incredible blind confidence and incompetence of his superiors, the young man had managed to siphon off money summing up to millions to his own use from the assets of the Union Bank of Switzerland.

The Union Bank of Switzerland had been founded in the city of Bern in 1864. It had four branches which were situated in St. Gallen, Lausanne, Geneva and, obviously, in Zurich. Director of the Zurich branch, which was opened on November 1, 1866, became Karl Stadler. He had conducted his own bank business before he took service with the Union Bank of Switzerland at an annual salary of 10,000 franks.

His subordinates were all men and women who had already worked in his liquidated bank company – all, with one exception: Emil Schärr. He had been recruited directly by the home office at Bern. With a look at his excellent references – Schärr had already worked for four different bank houses in the homeland and abroad with being only 19 1/2 years of age – he was appointed cashier, on bail at the amount of 20,000 franks. Schärr, however, didn’t own that much money to stand surety amounting to four annual salaries. Thus, five citizens of his native town Mümliswil vouched for him.

Most recently, Schärr had worked in Paris. During those years, he had become acquainted with a new kind of French book entry system the Union Bank of Switzerland planned to borrow for its accountancy. This system involved entering the final sums of the different accounts in a large account book instead of listing every single booking individually. It allowed grasping quickly profit and loss, although it required the individual bookings of the different accounts to be checked against each other.

Schärr was the only person in the Zurich office of the Union Bank who truly mastered the unfamiliar booking system. Everyone else – head, fellow employees, accounting clerks and auditors –, they all relied on him entirely. Thanks to his knowledge, Schärr became cashier and chief bookkeeper in personal union – and that was a splendid starting position to conduct defalcations on a grand scale.

Switzerland. 5 franks 1874 B, Bern. From auction sale Münzen & Medaillen GmbH Deutschland 31 (2009) 622.

Each day, an average of 880,000 franks ran through the books of the Zurich branch of the Union Bank of Switzerland. And Schärr helped himself generously by mis-entering the payments-in. That money he took for playing the stock market. Initially, he might very well have intended to simply “lend” the money off the Union Bank. It is likely that he hoped to earn enough by purchasing and selling shares to refund the bail of 20,000 franks to his fellow citizens with a grand gesture. But Schärr incurred losses. He was forced to embezzle further funds to make up the deficit and to continue participating in the big game at the stock markets.

Schärr’s activities didn’t go unnoticed. From the end of August 1869 onwards, bank director Stadler received serious warning upon serious warning. However, he remained confident. A contributing aspect may well have been that he considered his cashier an inspector of the Bern headquarters. Only a letter made him take action, a letter by his colleague in Geneva from September 28. This is what he wrote: “Mr. Stadler. A reliable source has confidentially informed me that our local cashier Schärr probably played at the Geneva stock exchange probably under the name of a syndicate and that he had differences amounting to 300,000 fr. payed to an insolvent broker in Geneva last week. In addition, there have been some inquiries about a certain ‘Directeur Schärr de la banque fédérale’ on the Geneva Square. We request that you call Cashier Schärr out on that most firmly and that you demand a plain and candid answer of him since, as you will surely understand, this is a matter of the highest importance to our organization.”

This made Stadler act, finally. In the morning of September 30, he interrogated his cashier. Schärr commented that there must have been a mistake. Stadler was satisfied and went to see a fire drill. When he returned to the office in the evening, he consulted with his procurator Wyss and decided to conduct a general audit that was scheduled for the following day. That allowed declaring the general audit as quarterly audit. When Stadler and Wyss came to their office the next morning and intended to start the audit, they found the vault cleared and Schärr gone.

The following weeks witnessed a huge police operation. 6,000 warrants of apprehension, including a photograph and a personal description, were sent to all major cities. A reward of 10,000 franks was offered for his capture. While the search for Schärr was under way, experts looked into the books of the Union Bank of Switzerland. The deficits that had ruined Schärr became the topic of the day: instead of talking about the personal state of affairs, the people of Zurich rather started their conversation with “Well, how big is the present deficit?” It was on November 29, 1869, during a stockholders’ meeting, that a preliminary sum total was stated: 3,248,658 franks and 17 rappen. That, however, wasn’t final yet.

While the bookkeepers totaled up the sum the humble cashier had robbed the large bank of, Schärr was finally arrested on November 9, 1869, when he crossed the border between Italy and Austria. He was put on trial in Zurich. The closing arguments were made on February 2, 1870. The prosecutor accused Schärr of trickery since he had used a book entry system that no one in the office really had understood.

That was precisely which Schärr’s defending lawyer called an incredible neglect, even stupidity on the part of the management which had made the embezzlements of Schärr possible in the first place. His speech for the defense ended with these words: “(The deed) have become possible only thanks to the fact that everything was left to the defendant unthinkingly, that is Bern and Zurich did precisely so – Bern without thinking twice, and Zurich because it took the cashier for a supervisor Bern had sent. … The young, inexperienced man had been led into temptation; don’t make a harsh judgement that he has fallen prey to it!”

The court’s deliberation took more than an hour. Schärr was sentenced to eleven years prison and to pay for the damage he had inflicted. The latter, obviously, ruined Schärr couldn’t do.

In the next episode, entitled “Rich and Poor” we accompany an American journalist who faces the social extremes of Zurich.

You can find all other parts of the series here.

The texts and graphics come from the brochure of the exhibition of the same name in the MoneyMuseum, Zurich. Excerpts with sound are available as video here.