The People of Zurich and their Money 7: The “Robbery” of the Church Silver

by courtesy of MoneyMuseum

Our series “The People of Zurich and their Money” takes you along for the ride as we explore the Zurich of times past. There was tension in the air in the autumn of 1526: The reformed Zurich had just expropriated the church on its territory.

Much like a good DVD, this conversation comes with a sort of “making of” – a little numismatic-historical backdrop to underscore and illustrate this conversation.

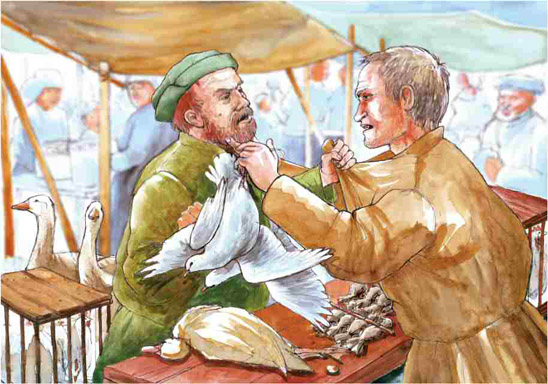

Autumn 1526. A citizen of Zurich and a citizen of Lucerne close a deal at the market of Baden. Drawn by Dani Pelagatti / Atelier bunterhund. Copyright MoneyMuseum Zurich.

Citizen of Zurich: It’s a deal.

Citizen of Lucerne: Done. One batzen for this pair of lean wild pigeons.

This certainly is not enough for these gorgeous creatures. With what kind of money do you want to pay?

With a batzen of Zurich.

Wonderful. (break, then shocked) But what is that?! Why is this batzen countermarked? This is a chalice? What’s that? Are you having me on?!

(first laughing, then angry) O no, in Lucerne all batzen of Zurich are now countermarked like this. Isn’t it correct? They are made of the silver from the chalices which you’ve stolen from the churches and cloisters. You’ve struck coins from the ill-gotten wealth. By rights these sacrilegious coins should be forbidden, forbidden – do you understand?!

Listen, you friend of all parsons, you are fattening the church while your paupers are starving! We in Zurich follow the pure and unadulterated Word of Christ. We took it from the rich church and gave it to the poor. We confiscated implements made from gold and silver valued at 14.000 gulden. These implements served only to flatter the vanity of donors and parsons, now 750 paupers can eat three meals a day for half a year! Isn’t the money now much better invested, when it’s spent for God’s images on earth?

Pious words indeed. And how much has reached the poor? Don’t bullshit me! Your government has found a way to replace the yearly 24.000 gulden which used to be paid for your lansquenets by the Pope! You’ve compensated for your budgetary deficit with precious donations given by generations of Christians for their salvation. You knaves of Zurich! Zwingli, this robber of chalices should be hanged by rights!

But …

We applied to have your coins made of church silver from the Swiss markets prohibited. This would have served you right. But these chickenhearted aldermen decided that the coins should circulate as long as they have the correct content of silver. Alright, may they circulate, but everybody should be made aware of where the silver in these coins comes from.

Shut up!

What shall I do? You’ll catch it … (ends in a scuffle)

Zurich guldiner (so-called chalice thaler) 1526. Mint master Niklaus Sitkust (1526-1533). From auction LHS 95 (2005), 337.

Making of:

Right after Zurich Council had laid claim to all church property during the Reformation, the question arose as to who exactly should become the new owner of the confiscated goods. In January 1525, the decision had even been made to abolish the obligation of restitution to private donors. As such, anyone who had donated a piece of land, a chalice, a chasuble or a reliquary in the past found his or her claims annulled in favour of the poor relief fund. On January 9, all the precious jewels were separated out of the confiscated church property, but at least temporarily, it was still unclear as to what the gold, silver, precious stones and pearls should be used for.

In September 1525, Council decreed, “that all silver and gold, and even the jewels and ornaments of the abbeys and monasteries in the city and the country be collected and handed over to the authorities.” It’s said that 14,000 gulden worth of material was gathered just in gold and silver alone. But rather than using this exclusively towards caring for the poor, as was originally intended, Council decided to have it made into coins. The proceeds were to be accrued to the Seckelamt (treasury office) and the alms office. In reality, however, the alms office came away empty handed, and it was in fact only the Seckelamt, the most important tax agency of Zurich, that received the newly minted coins. The coins served first and foremost to plug the gaping hole that had formed out of Council’s decision to put an end to all Reislaufen (mercenary service abroad). As such, the amounts that would have been paid to the treasury through the permission to recruit mercenaries were no longer available. The Seckelamt received over 24,000 gulden annually just from the pope’s funds alone.

Therefore, when it came to Zurich’s confiscation of church property, there was a huge gap between reality and moral claim – a fact noted with great anger in the Catholic cantons, in particular. Expressions like “rogues to Zurich” or “chalice thief Zwingli” became common terms. A woodcut from the year 1527 even depicts Zwingli hanging from the gallows, while Moses displays the tablets of the 10 commandments and points to a scroll containing the words “thou shalt not steal.”

This type of abuse and slander wasn’t just limited to the literary realm either. There are many substantial wars of words that have been passed down as well, just as they would have taken place between old believers and the reformed whenever they came into contact. Let’s take a look at this one example: In Constance, it’s said that Zwingli preached the following: “Whoever eats more of these foods [in the celebration of the mass] will shit that much more, and whoever drinks more of the drink [the sacramental wine], will piss that much more. The back and forth insults became so bad, in fact, that a separate article was included in the first peace that ended the first Kappel War in 1529, making defamatory speeches a punishable offense. Therefore, our two protagonists in the audio drama wouldn’t have seemed so out of place in the time after the Reformation.

The people of Zurich were particularly insulted when their own money began increasingly appearing on the market with privately embossed counterstamps in the form of a chalice. They attributed this new affront to the people of Zug and Lucerne. After a motion at the Lucerne hearing in 1526 failed to ban the Zurich batz that had been produced from the stolen church silver, it seems that this is how some private individuals took to expressing their opinion on the matter.

We know about the so-called chalice thalers and chalice batz thanks to a series of written sources from the Reformation period. The young Heinrich Bullinger devoted an entire multi-page manuscript to them, in which he defends the people of Zurich against the “outrageous” attacks. There’s even an image of these pieces in the Swiss-and Reformation chronicle of Johannes Stumpf. We, however, have never come upon a single, verified example of a contemporary chalice thaler or batz featuring the famous/infamous counterstamp.

In the 19th century, A. Geigy called upon the Swiss population to actually confirm the existence of such pieces by reporting them to the Swiss National Museum. And, in fact, three examples subsequently came into the possession of the National Museum, pieces that are today regarded with great suspicion by numismatists. This is primarily due to the fact that nothing is easier to forge than a counterstamp. And when a collecting institution’s need is so pronounced, it’s extremely tempting to deliver by producing a non-existent coin.

It’s also quite conceivable that none of these much-maligned pieces managed to survive the period from the Reformation up until now. After all, it was in the interest of those who counterstamped the pieces to bring them before the people of Zurich, and they would have almost definitely melted down all incoming pieces immediately.

Just one more quick note on the little wild pigeon that our individual from Zurich is selling at the Baden Market. The inspiration here was a little anecdote surrounding the Baden disputation of 1526. By Zwingli’s order, this was attended by a spy who reported back to Zurich daily about what the great theologians had been debating. This spy masqueraded as a chicken merchant. Sadly, we didn’t have a price for chickens from this year, as is the case with most prices from the 16th century, which have only been preserved in exceptional cases. So, we had to make do with a detail from the year 1562, when wild pigeons cost 4 shillings. During this decade, mind you, there was a substantial increase reported in the cost of grain. Whereas from 1520-1530, a bag of seeds cost 59 shillings, 10 pfennigs, by 1560, the cost had almost doubled. This is why we cut the price of the wild pigeon in our scene roughly in half. So, the estimated batz, converted to 2 1/2 shillings, is rather hypothetical.

As for the detail as to how many poor people could have been fed with 14,000 gulden, we’re going on the relatively high amount of 2 shillings for 3 meals a day. In actual fact, the poor would likely also have been satisfied with just one meal a day.

Just a bit later, people from Zurich invented a technology that was to open up a whole host of new possibilities for coinage: the rolling mill. You can hear more about it in our next episode “Zurich Technology Takes Over the World.”

You can find all other parts of the series here.

The texts and graphics come from the brochure of the exhibition of the same name in the MoneyMuseum, Zurich. Excerpts with sound are available as video here.