Who Was Frederick the Wise?

At first, a warning: if you have a firm opinion about the events of the Reformation, and if you do not wish to question this image, please refrain from reading this article. It deviates from the myth we internalized when we were in school. This article presents an alternative interpretation of the person of Frederick the Wise – that of a rather hapless politician who was monopolized by the Reformation and turned into its figurehead by means of excellent propaganda.

Frederick III the Wise, Albert the Bold and John the Steadfast. First klappmützentaler n.d., minted in Annaberg or Wittenberg. Very rare. Very fine. Estimate: 20,000 euros. From auction 358 (26 January 2022), No. 182. The obverse shows a portrait of the young Frederick the Wise, the reverse the portraits of the Saxon rulers who competed with him for power.

A Difficult Starting Position

On 17 January 1463, Frederick III, who became known as “the Wise” after his death, was born as the eldest son of Elector Ernest of Saxony. After Ernest’s death on 26 August 1486, Frederick took over the rule – not alone, by the way. He shared it with his youngest brother John, who resided in Weimar and could well have pursued independent policies. Another player in this game was their uncle, Albert the Bold. Even though the latter had agreed to the Partition of Leipzig one year earlier – a treaty that determined the division of the Ernestine and Albertine branches – nobody could say at that point whether Albert would honor this arrangement or not. Thus, Frederick III had to be careful, this came naturally to him as he was a careful person anyway.

His hesitation caused numerous political defeats. First, he failed to incorporate Erfurt into his territory, although the opportunity had virtually been handed to him on a silver platter. Then he failed to retain the guardianship of the minor Hessian landgrave. Not to mention the fact that, after the death of his two brothers, his family lost their bishoprics of Magdeburg, Halberstadt and Mainz.

And then there was his greatest defeat, which came about because he did not even dare to take up the fight for the imperial crown because of a rebellious Augustinian monk, even though Frederick would have stood a good chance against the other candidates – Francis I of France, Henry VIII of England and the Habsburg Charles I of Spain. He was a German prince, had a voice in the Electoral College and was by far the least powerful of the four candidates, a quality that electors greatly appreciated in emperors. The Habsburg Rudolf I had obtained the office because he combined these very characteristics. In addition, Frederick owned part of the inexhaustible silver mines of the Ore Mountains and had thus enough resources to come up with the necessary bribes. But history would have taken a different path if Frederick had ventured to take this step. Therefore posterity calls him “wise”; his contemporaries probably used other adjectives.

Frederick and Luther

But let’s go back in time a bit to understand why Frederick did not throw his hat in the ring. On 18 October 1502, he founded a university in his residential city of Wittenberg. That wasn’t unusual. Many rulers did that because their chancelleries were in need of lawyers and universities attracted the intellectual elite.

One of those who taught at the university of Wittenberg was the Augustinian monk Martin Luther. We don’t need to repeat his story at this point. It’s enough to say that things were getting rather hot for him in 1518. The Pope initiated legal proceedings against him, which jeopardized the reputation of Frederick III and his university. An excommunicated professor! Who would want to study at such an alma mater?

Therefore, Frederick III made an effort to crush the proceedings, even though he did not share Luther’s views. We know that Frederick was pious, made pilgrimages to Jerusalem and had assembled a gigantic collection of relics. Nevertheless, in a letter dated December 1518, Frederick demanded Cardinal Cajetan to scholarly discuss Luther’s theses once again before excommunicating him.

Emperor Maximilian I died as early as one month later. A new emperor had to be elected. For Frederick, there was no sense in competing for the office. The fact that Luther continued to cause sensations on end proved to all moderate forces in the empire that Frederick did not even have the authority to bring a professor of his own university to see reason. The result: Charles V was elected on 28 June 1519.

However, Frederick’s peaceful retreat had at least resulted in the others having enough consideration for him to give Luther a last chance to defend his theses in April 1521 at the Diet of Worms despite his excommunication, which had been declared on 3 January 1521. But Luther did succeed in convincing the members of the Diet. He was placed under the imperial ban. And Frederick III did not let him hang out to dry but negotiated a deal for his protégé that established that the imperial ban would not be enforced in Saxon territory.

Luther’s followers were thus given carte blanche. As early as in May 1521, the first priests married in Saxony. In January 1522, the Wittenberg Council – not the Saxon Duke! – adopted a new (Protestant) church order. Frederick outlawed it within the same month. But events had taken on a life of their own. In March, Luther returned to Wittenberg. Thus, Frederick lost what influence he had on what was happening. At some point, he probably had no choice but to put a brave face on it and to let himself be monopolized by the Reformation. Frederick died as early as on 5 May 1525. Protestant sources claim that he converted to Protestantism on his deathbed.

Frederick III the Wise. Guldengroschen n.d. Commemorating becoming Governor General. Very rare. Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 10,000 euros. From auction 358 (26 January 2022), no. 185.

Marketing the Reformation

And this paved the way for turning Frederick the Wise into an icon of Protestantism. One of the most ingenious artists of his time helped in this endeavor: as early as in 1505, Frederick III had appointed Lucas Cranach court painter and set up a workshop for him at Wittenberg Castle. Cranach was a genius, not because he could paint so well but because he designed a type of painting that was easy to recognize and that his assistants could produce quickly and cheaply by distributing different tasks between them.

Frederick the Wise and John. Broad guldengroschen 1523, Annaberg. Very rare. Very fine +. Estimate: 8,000 euros. From auction 358 (26 January 2022), No. 184.

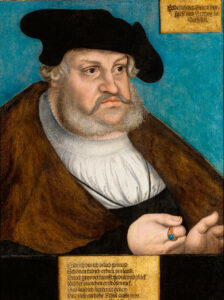

Frederick the Wise, painting by Lucas Cranach and his workshop. Portrait after 1525 with tablet written by Luther.

The portrait of the elderly duke became an iconic image. He is depicted with white sideburns and a black, velvet beret. Numerous pictures of him were and are on display in all important art collections because Frederick’s successors systematically distributed his portrait over the entire world at the time, mostly together with their own portrait. Thus, once the Reformation had become acceptable, they made sure to benefit from the glory of being the successor of Luther’s (involuntary?) patron.

A contemporary source tells us about the incredible volume in which these portraits were produced. On 10 May 1533, Duke John paid the painter Lucas Cranach 109 guldens and 14 kreuzers for creating 60 small pictures of Frederick and 60 small pictures of him.

By the way, these portraits weren’t the only things to be shipped around the world. Most of them came with a legend that explains how John wanted his brother’s fate to be interpreted. The poem, written by Luther himself, states that Frederick had kept the peace in the empire by means of reason, patience and lucky fortune as he faithfully elected the emperor without putting himself first. He – Frederick – founded the university in Wittenberg, where God’s word emerged (this is how Luther liked to speak about himself; author’s note), with the help of which the papal power was overthrown and the right faith returned.

German Empire. 3 marks “Frederick the Wise”. Proof. Estimate: 100,000 euros. Hammer price: 130,000 euros. From Künker auction 350 (29 June 2021), No. 2078.

This is the image of Frederick the Wise we internalized, so much even that it was possible for a 1917 coin of the German Empire to feature his portrait instead of Luther’s on the occasion of the 400th anniversary of the Reformation.

Here you can find the Künker auction 358 online catalogue.

And we also published a comprehensive preview of Künker’s January auction sale 2022.