How Two Fraudsters Almost Changed England’s History

By Björn Schöpe, translated by Rachel Agard

Two men in England have now been sentenced after attempting to sell illegally excavated coins from the Early Middle Ages over the Internet. This successful outcome is thanks to the efforts of a radiology professor in the USA, as well as a year-long police operation. The result? A whole new perspective on England’s history during the reign of Alfred the Great.

Content

Viking Coins By E-Mail?

Let’s begin in the middle of the story, in 2018. Craig Best, now 46 years old, sent an email to Ronald Bude, a radiology professor at the University of Michigan – and a coin collector who has also published on numismatic subjects. Best sent Bude photos of silver coins dating back to the Early Middle Ages and offered to sell them to him. He wanted 200,000 to 250,000 pounds for them. In fact, the coins were so rare that Bude initially thought they were forgeries, so he decided to consult experts at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. When Best heard that, he emailed Bude again, rather annoyed this time: “They are a hoard as you know they are this can cause me problems all you had to do was say you didn’t want them and that was the end of it.” Indeed the numismatists informed the police in Durham. The experts immediately suspected that these spectacular silver coins had come from the famous Herefordshire Hoard. Best had told Bude that they came from the area of Worcester, around 30 miles from where the hoard was found.

The Herefordshire Hoard

The Herefordshire Hoard is a sad reminder that even England’s liberal regulations for metal detectorists are not immune from abuse. In 2015, two detectorists near Eye in Herefordshire stumbled on an estimated total of around 300 coins from the 9th century. They had been on the site without the landowner’s permission, and should have reported this discovery within two weeks at the latest. A hoard like this would have been declared as treasure. As such, it would certainly have been put in a museum, while the finders would have been entitled to a reward and may even have come out of the whole affair as celebrated millionaires.

But the two finders wanted more. They kept their discovery quiet and started selling off the hoard piece by piece. By the time the police arrested them, there were only about 30 coins remaining that could still be linked to the hoard. In 2019, both men received long prison sentences.

Going Undercover: Operation Fantail

It appears that this major hoard also contained the coins that Best tried to sell. After he failed to reach a deal with Bude, another option opened up. At a hotel in Durham, he met up with some men he believed to be representatives of an American buyer. He showed them three coins – and then realised he was out of luck. The men were undercover police investigators and they arrested Best there and then.

Best had been given the coins by a fellow detectorist, Roger Pilling, now 75 years old. Pilling allegedly asked him to sell the coins, assuring him that they came from a hoard found before 1996 – i.e., before the introduction of the Treasure Act requiring hoards to be reported to the authorities within two weeks of being found.

Sentenced For Fraud and Conspiracy

Pilling and Best do not have any previous criminal convictions and were described during the two-week trial as hard-working family men. The judge James Adkin said he was convinced that the coins seized from Best and Pilling during the investigation, a total of 44, had come from the Herefordshire Hoard. The jury found the men guilty of conspiracy to sell criminal property and possession of criminal property, after which they were each sentenced to five years and two months in prison.

They obviously had nothing to do with the discovery of the hoard, but Pilling did not disclose how he had come by the coins. The historical significance of these coins probably prompted the court to make an example of the detectorists.

Alfred the Great is certainly still great. But he did not shape England entirely without help, as the newly discovered coins show.

These Coins Rewrite England’s History

The British media was almost overzealous in its coverage of the coins. Some reports have been throwing around figures for the presumed value of the hoard, with guesses reaching up to “around £3 million”. This is of course speculative, as we don’t even know the exact number of coins. The 44 seized coins alone are said to have an estimated market value of 766,000 pounds. More importantly, however, the coins that Best was attempting to sell are extremely exciting from a historical perspective. Gareth Williams, Curator of Early Medieval Coinage at the British Museum, is quoted as saying: “The coins literally enable us to rewrite history.” Is he exaggerating?

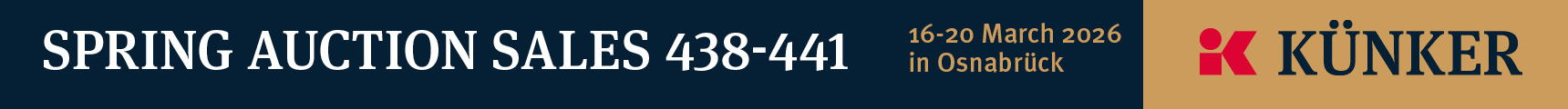

The coins date back to around 870, when Alfred the Great, King of Wessex, fought off the Vikings who were settling in England almost single-handedly, uniting the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms under his leadership. But did he really have no help whatsoever? Unlikely.

At least one of the coins appears to be from a joint issue shared with another ruler, Ceolwulf II, King of Mercia. Historians have long regarded Ceolwulf as a sort of puppet ruler who was at the mercy of the Vikings. However, this coin reveals that he was clearly an important ally of Alfred the Great.

The coins are still being thoroughly examined at the British Museum and are to be displayed at Hereford Museum from 2025, when the museum’s renovations will be complete. The museum has raised 776,250 pounds to purchase them.

The Current Situation For Metal Detectorists in England

It is quite clear that both the original finders of the hoard and the two metal detectorists who tried to sell on the stolen goods were breaking British law. However, the Treasure Act of 1996 has now been tightened up once again. Previously, it stipulated that only objects that were older than 300 years and contained precious metal, or which were part of a collection or a larger group of finds (such as a hoard of coins), could be declared as treasure. This definition did not include, for example, the eminently significant Crosby Garrett Helmet (which was not part of a hoard and did not contain any precious metal). It was purchased by an anonymous private bidder for 2.3 million pounds, a price that public museums simply couldn’t compete with. Now, this would no longer be possible.

According to the new version of the Treasure Act, all objects that are at least 200 years old and contain metal can now be defined as treasure. This also includes all coins made of base metal or other metal items, such as weapons or pieces of armour. If found, these items must be reported within two weeks, otherwise the finders are liable to prosecution.

Arts & Heritage Minister Lord Parkinson of Whitley Bay summarised the change in the law as follows: “There has been a huge surge in the number of detectorists – thanks in part to a range of TV programmes – and we want to ensure that new treasure discoveries are protected so everyone can enjoy them.”

Alan Tamblyn, General Secretary of the National Council for Metal Detecting, echoed this sentiment, and emphasised the council’s support for this increased protection of significant finds.

One aspect that hasn’t changed is the need for cooperation and mutual trust and respect between detectorists and academics; this, after all, is what makes England’s legislation so successful.

The English media has reported extensively on the trial. For example, the Guardian: