Poets and their income: William Shakespeare

translated by Christina Schlögl

There are only few poets who have bestowed us with as many proverbs as Shakespeare has. This may also be due to the fact that Shakespeare was the first writer, whose works were not exclusively targeted at a generous aristocracy. Shakespeare and his generation invented the commercial theatre, which gave everyone the opportunity to be entertained for little money. No wonder it was “cool” in London at the beginning of the 17th century to say one or two quotes to show that one had crossed the River Thames to catch the current theatre production at the Globe. And some quotes were simply good enough to still be used until this day.

Reconstruction of the Globe Theatre. Photo: Tohma / GDFL.

Theatres like the Globe were large commercial businesses and belonged to a community of actors, who shared in the profit and loss of the company, just like in a stock corporation. Shakespeare was one of eight (later twelve) members of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, which meant that their income was not solely based on theatre but also on their patron’s contributions. Such a patron would also protect his artists against the imponderabilities of the English law and provide royal patronage. Therefore the Lord Chamberlain’s Men were also supported by King Jacob I after Queen Elizabeth I had died and renamed themselves King’s Men.

Their performances at court were lucrative. Queen Elizabeth used to spend 10 pounds for one show. The King’s Men were especially busy during Christmastime. In 1603, King Jacob I paid 80 pounds for the six performances they had given at the royal court. This was a princely salary, which could be seen as a kind of deficiency compensation, since it had mostly been impossible to hold shows during the previous year. The plague that year had bought the group to the brink of a financial catastrophe.

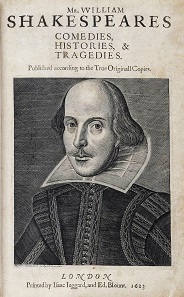

William Shakespeare. Portrait on the legendary “First Folio-edition” of his works.

The aristocracy’s support and their funding was pure luck, though. One could not rely on this form of financial support. It was thus important, to build a solid base for operation “theatre”. And the troop’s income did not only consist of admission fees.

Whoever went to the theatre was certainly willing to spend some money. And they had to, since practically every step cost money. First one had to pay fourpence or sixpence for the ferry. In comparison, the entrance fee for the court of the Globe seems almost cheap. It cost one penny. This did not include tickets. The money was put into small cash boxes at the entrance, strictly controlled by guards. In order to reach the first seated area, one had to pay a second penny into one of the cash boxes. This penny gave the gallery its name. It was commonly referred to as the “twopenny gallery”. And then there was a third balcony with cushions and a good view of the stage. This is where the third penny went into the box.

Elizabeth I, 1558-1603. 6 Pence 1562, London. From Künker 241 (2013), 2245.

Naturally it was unthinkable to force the refined society of London to make their way through the crowded galleries with the other theatregoers. That is why there were special balconies for those, who felt superior to the hoi polloi. Access to these balconies cost one shilling, which is 12 pence, and they had a separate entrance from the outside.

The audience could be charged double for premiers by the way. And small, overlaid theatres – performances were given regardless of wind or weather, even during the “Little Ice Age” – were in a whole other dimension. Their entrance fee was sixpence, and the seating ares we would call loge today cost 2 shillings and 6 pence, 30 pence as a whole, which was a treat only few people could afford.

In addition to the entrance fee, there were other things sold at the Globe. Food and drink, for instance, were allowed at all times. One Swiss visitor of the Globe wrote: “During the shows, food and beverages are carried around and sold, so that one can always get refreshments if one is willing to pay for them.”

One type of beverage sold at the Globe was bottled ale. We know this, because during the fire at the Globe in 1613, a man’s burning trousers were extinguished with ale. Apples and nuts, oysters, ginger bread and sweets were also offered, consumed and thus generated a decent pin money for the owners of the Globe.

Jacob I, 1603-1625. Shilling undated (1619-1625). From e-Auction Rauch 18 (2015), 1366.

Current estimations assume that the Globe Theatre had a yearly income of around 1,200 pounds. This means that Shakespeare’s share of the profit – also estimated by contemporary scientists – was 40 pounds, which was not an insignificant amount either. A gentleman could indeed make a living from this kind of income.

The 1,200 pounds of income stood against 420 pounds of spending, which consisted of costs for scripts, actors, staff, costumes and charges.

Jacob I, 1603-1625. 1/2 Laurel (= 10 Shillings) undated (1619-1620). From Künker 230 (2013), 6650.

Shakespeare did not only earn money from his share of the theatre, but was also paid as an author. We know little about the Globe, but other theatres paid between 5 and 8 pounds at the beginning, which soon rose to 10 and 12 pounds for a manuscript. Shakespeare’s colleagues published 36 plays as a sort of collection in the year 1623, which must have yielded a nice profit. The book cost 1 pound!

Today, two more plays are attributed to Shakespeare. We know of two lost works from literature. How many more works have got lost? The 38 known works earned him 266 pounds, given an average income of 7 pounds per play. This sum allowed for a nice gentleman’s life of about 7 1/2 years. And this is not even taking into account that Shakespeare was also paid for adaptions of other authors’ plays.

In addition to honorariums, there was also the “second night privilege”. All income generated by the second performance of a new or a revamped play belonged to the author. At times, this would be quite a lot of money. The second night of Othello earned the theatre 9 pounds and 16 shillings. Thus this privilege ought to have doubled Shakespeare’s income as a playwright.

In addition, Shakespeare also performed as an actor and must have also got a fee for it. Albeit actors were not paid all that well. They had an average income of 10 shillings per week, which was between 10 and 15 pounds per year. That was roughly as much as a normal worker would make in one year.

Historic costumes at the museum of the Globe Theatre / London. Photo: Reni002 / CC3.0.

Therefore the actors were of no consequence. What was expensive however, were the costumes, especially for plays that were set in aristocratic circles. We know how much the costumes of “Cardinal Wolsey”, a play first performed at the Fortune Theatre in 1601, cost: 37 pounds. Incidentally, most of the time, these costumes were not specially made for the productions but instead came from the estates of deceased nobleman and noblewomen, who had left their clothes to their servants as an inheritance.

All in all, Shakespeare’s yearly income is estimated at 100 pounds. This was an extraordinary sum, which is comparable to the income of a contemporary star author by all means. And this is still accurate despite the fact that Shakespeare had to renounce the biggest source of income present-day authors have: copyright. The profit from the first publication of his works was not given to his descendants but to a syndicate responsible for printing his works.