Silver for Württemberg

In the early modern period, much of the Black Forest, an idyllic mountain range in southwestern Germany, was a booming industrial center. A major part of the silver used to mint Württemberg coins came from this region. The Heinz-Falk Gaiser Collection, on offer at Künker on 23 September 2024, includes many coins made from Black Forest silver.

Content

In the early modern period, much of the Black Forest, an idyllic mountain range in southwestern Germany, was a booming industrial center. A major part of the silver used to mint Württemberg coins came from this region. Background image: Ramessos via Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0. Coin: Künker Auction 410 (23 September 2024), No. 834.

In 1570, the whole of Europe was suffering from a severe famine. This was the first time that the impacts of the Little Ice Age really made themselves felt. Dutiful rulers such as Duke Louis of Württemberg distributed their grain supplies to the starving population. But their supplies quickly ran out.

How could a ruler raise the funds to buy new grain and to cover the increased costs his administration was faced with? In this situation, Duke Louis hired an outside expert to examine whether the silver mines in the Black Forest should be reopened.

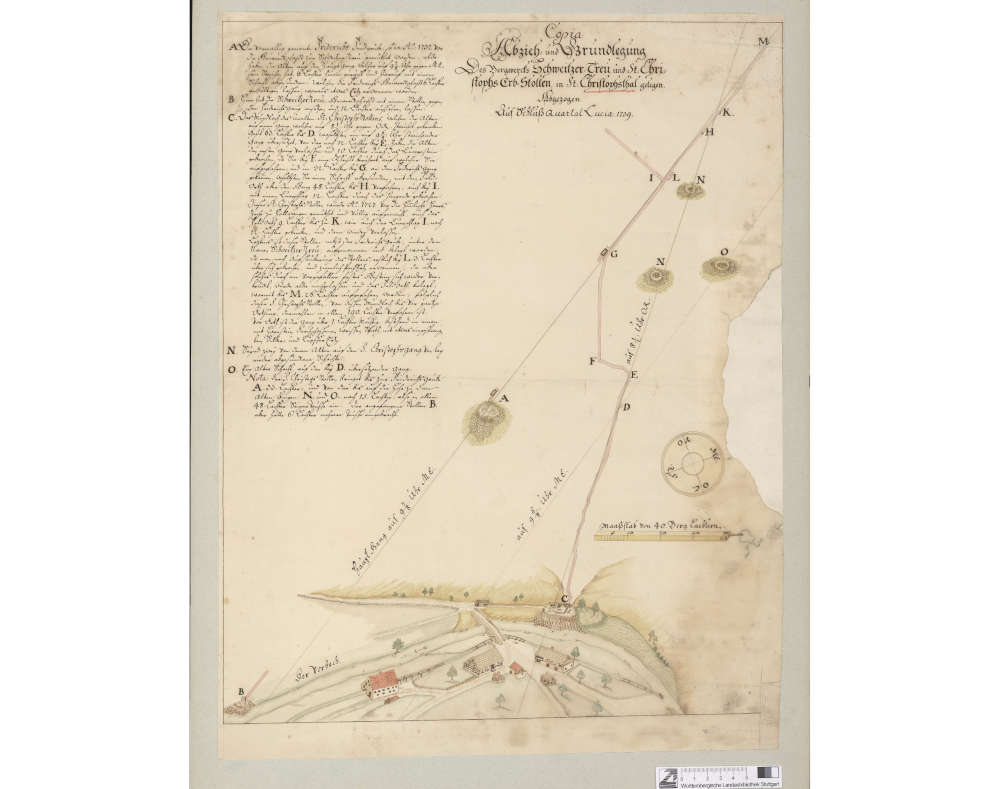

Abzieh= und Grundlegung Des Bergwercks Schweitzer=Treu und St. Christophs Erb=Stollen in St. Christophsthal gelegen Abzieh= und Grundlegung Des Bergwerks Schweitzer=Treu und St. Christophs Erb=Stollen in St. Christophstal gelegen. Württemberg State Library Stuttgart — Schef.fol.1004. Public Domain Mark 1.0.

Silver from Christophstal

The expert recommended that the “mines of Forbach” resume operations. The Christophsstollen (Christoph’s tunnel) named after Louis’ father was particularly promising. It would give its name to the entire mining region: Christophstal (Christoph’s Valley). As early as in 1573, the first talers were produced from Christophstal silver. They depict St. Christopher, the legendary giant who carried Christ across a river.

To attract skilled workers from near and far, Duke Louis granted the mining region a number of privileges. He allowed citizens to buy and sell property without paying taxes, which was uncustomary at the time. The right to settle in Christophstal came with the freedom to conduct a business – another attractive privilege. In addition, Louis allowed the settlement to hold a weekly market and one or more annual fairs.

However, the amount of silver produced was rather limited, as we can see from official accounts of the time. In 1575/6, the mines produced only 3.605 kg, and in 1579/80 even less, namely 1.637 kg of pure silver. Duke Louis decided to stop state subsidies. But private entrepreneurs continued to operate the mines. We know this because, according to administrative records of the time, a large amount of silver was delivered to the mint in 1585: “On 29 April 85, silver from the mine in St. Christophstal was delivered to the mint, and struck into talers with the head-and-shoulders portrait of my gracious prince and lord. We had 502 guldens, 18 schillings and 1 pfennig [worth of silver] in our melting pot, and [minted it into coins worth] 519 guldens. Thus, according to accounting records, we made [a profit of] 10 guldens, 23 schillings and 5 pfennigs over and above the expenses.”

Louis the Pious of Württemberg. 1585 taler, minted from the silver of the Christophstal mine. Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 15,000 euros. From auction 411 (23 September 2024), No. 800.

The Coin Distributed at the Duke’s Wedding

The description tells us what silver this coin was struck from and how many coins were made from it: one of these 458 coins will be auctioned off in the upcoming Künker auction 411 as part of the Heinz-Falk Gaiser Collection. It is an exceptional issue that was not intended for circulation. The design did not meet the requirements of the Imperial Minting Ordinance. Instead, the coin was created to be distributed among the guests of the wedding of Duke Louis and Ursula of Pfalz-Veldenz.

On the obverse we see the duke in full armor without a headdress. In his left hand, he holds a commander’s baton. His left hand is resting on the hilt of his sword. On the reverse is the personal coat of arms of Louis III with his motto NGW (= Nach Gottes Willen / Following God’s Will). There is no reference to the 13-year-old bride on the coin.

Frederick I. 1607 taler, minted from the silver of the Christophstal mine. Extremely fine. Estimate: 10,000 euros. From auction 411 (23 September 2024), No. 816.

The Peak of Württemberg as a Mining Region Under Frederick I

In 1593, Frederick I took office. He was a “modern” ruler who focused on state-controlled, mercantilist economic policies. This also included the exploitation of local raw materials using the latest methods, which were significantly more costly but would prove lucrative in the long run. In 1594, Frederick ordered investment in the silver mines of Christophstal. As early as in 1595, annual production exceeded 100 kilograms of pure silver for the first time. In 1595/6 Frederick therefore had a new smelting works built on the site. And in 1598, modern waterworks were added to drain the tunnels at a lower level.

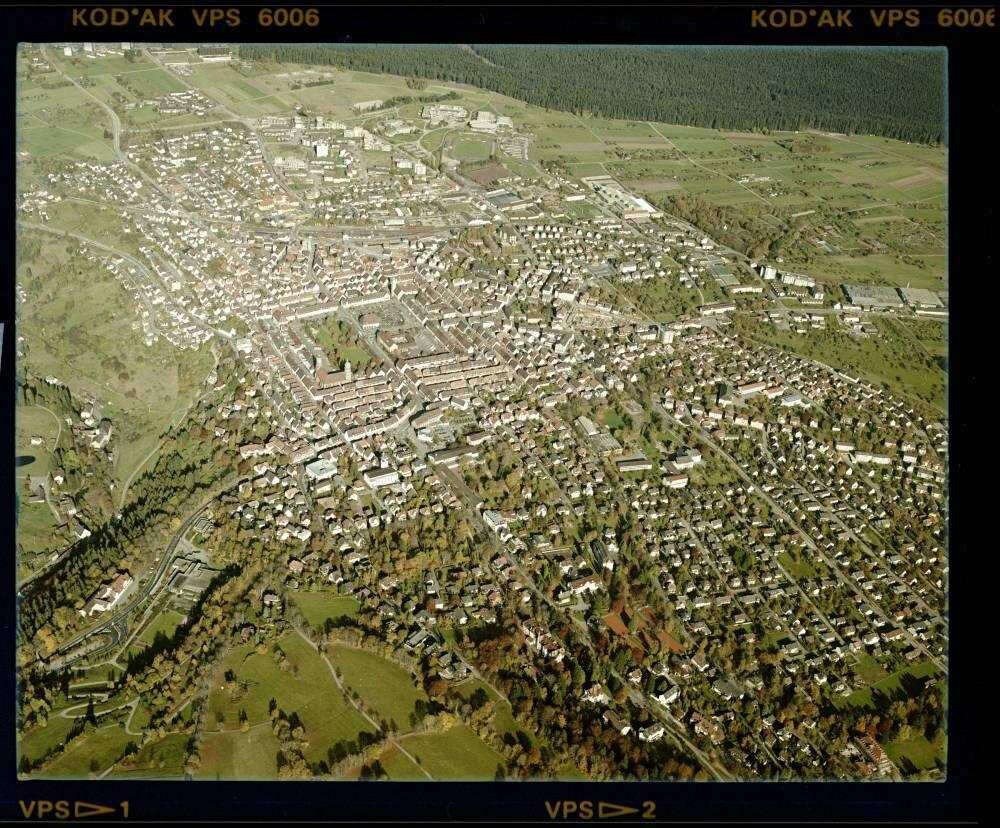

The municipality of Freudenstadt from above on 30 October 1984. The geometric inner structure of the city is clearly visible. Photo: Erich Merkler, Grosselfingen. Baden-Württemberg State Archive. Public Domain Mark 3.0 Deutschland

The Founding of Freudenstadt

In all his endeavors, Duke Frederick had a good and experienced advisor. The latter also recommended that the miners be given title to plots of land to build on, in order to tie them more closely to their work through their newly acquired ownership. We know what Frederick thought of this proposal because he noted at the margin of the report “that we do not object to this, but find that small huts and gardens should be built in [one and the same] place, so that a town can be created.”

On 22 March 1599, Duke Frederick had the first plots of land surveyed on a plateau above Christophstal. On 1 May 1601, the foundation stone for a Protestant church was laid. The new name of Freudenstadt was first mentioned on 6 May 1599.

The town became known beyond its own region on 3 November 1601. A document from this day has survived in which the duke invited religious refugees from Styria, Carinthia and Carniola to come to Freudenstadt. Many came, but only a few stayed.

Jägerndorf. John George, 1601-1621. Broad double reichstaler n.d., Jägerndorf. Very rare. Extremely fine. Estimate: 10,000 euros. From auction 410 (23 September 2024), No. 401.

Freudenstadt as the New Capital of Württemberg?

In 1999, the Freudenstadt politician and regional historian Gerhard Hertel suggested that Freudenstadt had not been founded as a mining town, but to become the new capital of a Württemberg that was expanding westward. Hertel argued that the historical context of this westward expansion was the Strasbourg Bishops’ War. In Strasbourg, too, part of the cathedral chapter tried to get rid of the restrictions of the Catholic faith. After the bishop’s death in 1592, they therefore brought John George, the second-born son of Margrave Joachim Frederick of Brandenburg, into their territory and elected him administrator – in a violation of all provisions of the Peace of Augsburg and the reservatum ecclesiasticum of 1555. This was opposed by a Catholic minority in the cathedral chapter, who elected Charles of Lorraine as the new bishop. War broke out, and the princes of the surrounding territories took advantage of the situation. Duke Frederick, for example, forced John George to give him the administrative office of Oberkirch in return for his support. Württemberg thus shifted slightly to the west.

Hertel erroneously calculated that Freudenstadt was designed for up to 3,500 inhabitants, making it a large town by 16th-century standards. In fact, far fewer people lived there. Depending on the calculation, the first plan provided for 312, 338 or 375 citizens, which was roughly the size of Blaubeuren at the time. Blaubeuren was the 23rd largest of the 64 towns in Württemberg in 1598. So Freudenstadt was far from being a capital city. We should rather think of it as a regional center. This also fits better with the town being located on a snowy hill. Especially during the Little Ice Age, it was cut off from the rest of the duchy for months at a time. It would have been extremely difficult to administer the duchy from Freudenstadt.

In any case, Frederick’s plans to expand Württemberg to the west came to nothing. John George handed over Strasbourg in 1604 in exchange for financial compensation. The Margrave of Brandenburg thus gave his son the County of Jägerndorf in Silesia. A very rare double taler depicting the former administrator as count comes from this region.

John Frederick. 1609 reichstaler, Christophstal. Very rare. Very fine +. Estimate: 7,500 euros. From auction 411 (23 September 2024), No. 840.

Neglected by John Frederick

When Duke Frederick died in 1608, he was succeeded by his son John Frederick. The latter did not invest as much in the silver mines of Christophstal as his father had, and profits steadily declined. While Christophstal had still delivered about 108 kilograms of fine silver to the Stuttgart Mint in 1608/9, the yield had fallen to less than half that amount by 1609/10. Nevertheless, Stuttgart continued to mint talers from this silver, such as this 1609 reichstaler depicting St. Christopher.

John Frederick. Debased half gulden from the Kipper und Wipper era (30 kreuzers), 1622, Tübingen. Very rare. Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 1,500 euros. From auction 411 (23 September 2024), No. 846.

Christophstal Gets Its Own Mint

Albert Raff was able to prove that there had been no mint in Christophstal prior to the financial crisis called “Kipper und Wipper”. This changed when the territorial princes saw an opportunity to make excellent business by issuing debased coins. Christophstal was the perfect place to carry out this state-run minting scam: it had everything you needed – staff, a few machines, and the wood needed for a mint. In addition, Christophstal had good transportation connections. Large quantities of poor money were minted here before John Frederick returned to minting regular coins in the summer of 1623. Unfortunately, there are no Kipper und Wipper coins from Freudenstadt in the Gaiser Collection. Therefore, we show you a half gulden from this era from Tübingen with the mint mark T.

After all, a new mint was also installed in Tübingen, and its mint master actually should have produced the dies for his colleagues in Christophstal. Instead, economic war broke out between the Tübingen mint master Peter Stein and David Niederländer, his counterpart in Christophstal. They fought with all the means at their disposal – slander, poaching and other forms of damaging each other’s business. The conflict did not end until the Tübingen mint was closed down on 11 May 1623.

John Frederick. 1624 taler, Christophstal. Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 1,500 euros. From auction 411 (23 September 2024), No. 834.

Christophstal continued to produce coins for a few years. Coins from this mint are easily identified by the CT mint mark.

After the death of John Frederick in 1628, the mint of Freudenstadt was closed. Silver from Christophstal was again sent to Stuttgart to be struck.

But the Thirty Years’ War put an end to that as well. In 1634, Freudenstadt was plundered by the imperial army, which brought mining activities to a halt. Although mining operations were resumed after the Thirty Years’ War, it took a long time before the mined silver was struck into mining coins again.

Heinz-Falk Gaiser, who grew up in the region of Freudenstadt, was particularly interested in the issues of his first home town. Therefore, his collection contains quite a large number of coins from Freudenstadt, which are usually very difficult to find.

Bibliography

Franz Kirchheimer, Die Bergbau-Gepräge aus Baden-Württemberg. Freiburg (1967)

Uwe Meyerdirks, Bergbau und Stadtentwicklung im Nordschwarzwald. In: Martin Pries und Winfried Schenk, Rohstoffgewinnung und Stadtentwicklung. Geographie 30 (2013), pp. 59-111

Albert Raff, Die Bedeutung von Christophstal für die württembergische Münzgeschichte. In: Freudenstädter Beiträge 9/1999, pp. 5-87