The Colts of Corinth

by courtesy of Dr. Hans Voegtli / ACAMA

CORINTH. Stater, 500-485 BC. Pegasus with curved wings flying to l. Rev. Small quadripartite incuse. 8,46 g. Ravel I, 54, 80 (same dies). BMC 2, 19 (same dies).

This beautiful early stater of Corinth bears Pegasus on its obverse. The winged horse was the symbol of Corinth and each citizen of this important seaport felt the whole city and himself connected with this winged horse. Why did he do so and how did this connection come into being?

Most Greek coins of the archaic and classical period show gods and their symbols to demonstrate that a city was closely connected to a certain deity. The fact that a god or a goddess loved a city seemed to guarantee military, political and economical success. Another subject on coins were the real or mythological “proves” that a god favored a city. Let us list a few examples: The silphium on the coins of Cyrene was certainly not a PR gag of the silphium farmers. This precious plant manifested that Zeus Ammon loved Cyrene, otherwise he would not have presented the lucrative silphium – which grew exclusively in that part of the world – to the inhabitants of Cyrene. The quadriga crowned by Nike, which we know from Sicilian coins, refers to the many victories of Sicilian citizens at the Olympic games. Being the winner in a ritual contest proved that the god to whom the competition was dedicated favored the winner’s hometown. Arethusa was shown on the reverses of the archaic and classical tetradrachms of Syracuse, because the inhabitants of this city considered it a piece of evidence of divine grace that their well of fresh water sprang from the island of Ortygia surrounded nearly completely by salt-water.

In the same way Pegasus was a sign of heavenly benevolence that was offered to the citizens of Corinth. His taming was closely connected to both of the most important deities of Corinth, to Athena Chalinitis and Poseidon Danaios. Most of us know Poseidon only as god of the sea. But this was just one of the aspects of his power he had in the eyes of a Greek believer. He was observed in the indomitable natural power beyond men’s control, in the earthquake, in the towering waves, in the untamed stallion prancing and the wild bull attacking. The untamed horse Pegasus as well belonged to the creatures ruled by Poseidon.

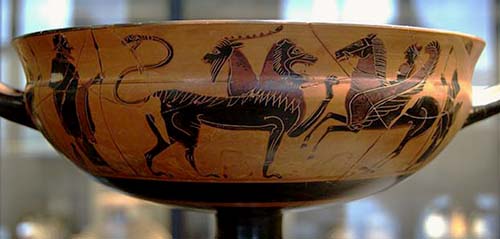

Bellerophon riding the Pegasos, fighting against Chimaira. Vessel painted by the Heidelberg-painter, ca. 575-550, found in Kameiros (Rhodes), Louvre /Paris.

Bellerophon, hero of the Corinthians, was supposed to be the son of Poseidon. One day he saw Pegasus and started to yearn for owning the beautiful horse. Pliny the Elder delivers us that in those days the art of riding was not yet invented. Therefore Bellerophon could only gaze after the magnificent horse without any chance to get it. But one night Athena appeared to Bellerophon in a vision. She gave to him a golden bridle to tame and ride the Pegasus. She ordered him to sacrifice to his father Poseidon to thank him for the beautiful horse. She also wanted to be honored for her help by a shrine. So Bellerophon – vicarious for all inhabitants of Corinth – was granted a favor from two deities and he thanked them by starting their worship in the city of Corinth.

This story was the most important myth of the Corinthians. The narration told all citizens, why both of their most important cults came into being. Besides that, the myth enlightened the believers on the way Athena or Poseidon would appear. Poseidon was hidden in the natural powers. He was the one who claimed a sacrifice to tame the wild nature of a horse before it was to be ridden, or to calm down the waves of the sea to give a secure journey. Athena was responsible for every good idea that promoted the progress in civilization. She gave Bellerophon the bridle, an invention that made riding possible.

Using animals to make life easier is a progress, if you compare it to hunting and eating them. Individuals who invented new techniques were thought to be inspired by Athena. Corinth, a centre of manufacture and trade, was dependant on Athena who guarded the clever craftsmen and on Poseidon who watched over the bold seamen. Pegasus was the reminder to every Corinthian that Poseidon and Athena would protect their city as long as all Corinthians would exercise the acts of worship their mythological fellow-citizen Bellerophon had initiated.

G. Bethe, s. v. Bellerophon, RE 5 (1897), 241ff.

L. Bruit Zaidman, P. Schmitt Pantel, Die Religion der Griechen, München 1994.

U. Kampmann, Gottheit und Polis, Stuttgart 1999.

W. Rathmann, s. v. Pegasos, RE 37 (1937), 56ff.

O. E. Ravel, Les “poulains” de Corinthe, Basel 1936.

J.-P. Vernant, L’univers, les Dieux, les Hommes, Paris 1999.