And this is where Aristotle was wrong…

Aristotle, in his work on the structure of the Tarentine government, likewise described the coins of the city. He remarked that they depicted Taras, son of Poseidon, riding a dolphin.

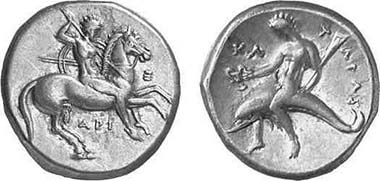

Tarentum, stater, 325-281. Fischer-Bossert 925. From auction Gorny & Mosch 118 (2002), 1096.

As a matter of fact, on the South Italian coins we do find a young man who rides a dolphin and holds an object in his hand on most specimens. On this coin he holds a kantharos and a rudder, but there can be found spindles, jugs, wreaths, small dolphins and countless other things as well. To the figure’s right the inscription TARAS is discernible, hence the nominative of the city of Tarentum which is quite unusual for a Greek coin. Ordinarily, the coins are designated with the genitive plural, therefore not Syracuse but (coin of the) Syracusans – to mention only one of countless examples. Aristotle concluded that the term Taras didn’t denote the minting authority but the one represented, i.e. the name-giver of the city of Taras.

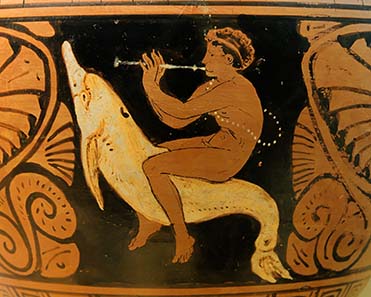

Juvenile flute player on a dolphin. Archeological Museum, Madrid. Photo: Maria-Lan Nguyen / Wikipedia.

Unfortunately, Classical tradition doesn’t know of a Taras riding a dolphin. It connected that wandering legend, which often appears as part in other local myths as well, with Phalanthos whom the Tarentines revered as their founder. The founding legend of the city of Tarentum had it that long ago the sons of Spartan women and Helotes, a kind of slaves in service of the state in Sparta, rebelled against the governing Spartiates. Their leader was Phalanthos. The rebellion failed, the rebels were forced to exile and established, led by that very Phalanthos, a new city, Tarentum, conveniently situated near a natural harbor. We know even more about his life. He is said to have pilgrimaged to Delphi in order to ask for rain on behalf of his city – when, on his journey, he came into distress a dolphin had rescued him. Tarentum faced a problem: there was no tomb of Phalanthos present. That was quite unfortunate since it was common practice to bury a city founder in the middle of his foundation so that he could protect his city beyond death. The resourceful Tarentines therefore adhered to the following legend: they had expelled Phalanthos themselves who died in exile in Brentesion. He, on his part, didn’t hold it against them. Phalanthos returned to Tarentum: his bones were translated to the city and spread on the agora.

Tarentum. Stater, flattened. Vlasto, Oikistes 1A, a. From auction LHS 95 (2005), 433.

Hence, there are two Tarentine heroes but, unfortunately, not a single piece of evidence of their true existence. The only thing we know is that they co-existed in the belief of the Tarentines. This is confirmed first by Pausanias who, in his description of Greece, speaks of a votive in Delphi which showed both heroes side by side, and, secondly, by the city’s coins minted at the beginning of the 5th century which depict two different heroes with the same inscription on both sides: a man enthroned on a low seat with kantharos and spindle and the above mentioned dolphin rider.

It is safe to assume that the dolphin rider is Phalanthos for all contemporary legends refer to him as the one riding a dolphin. Aristotle simply misinterpreted the inscription on the coin. He didn’t know that some Sicilian and South Italian cities didn’t use the genitive plural on their coins – as was common in the mainland –, but the nominative singular. By the way, that was a mistake with consequences up to the present day. Many auction catalogs speak of Taras in their description of the dolphin rider.

We can go even deeper and do some research on where Taras and Phalanthos allegedly originated from. There were absolutely no historical figures. Taras is said to have been the name of a river where the city was founded, later to be known under the river’s name. Phalanthos, in contrast, may be associated with an age-old deity revered in the guise of a dolphin rider for whom the legend was tailor-made. That example testifies the complexity of the Greek mythology, much more complicated that we would believe after reading Gustav Schwab’s Klassische Sagen des Altertums.

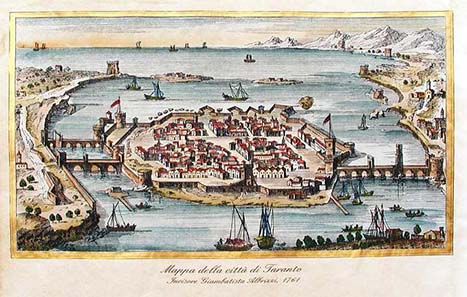

Tarentum in the 16th century. Source: Wikipedia.

Let us have a look at Tarentum whose coinage is indicative of the city’s significance in antiquity. Today, the wrecking ball would be in order for Tarentum. The ancient city is overgrown by half-wasted palazzi, by houses closer to their destruction than their construction. Ancient relics are seldom. The National Museum with its precious gold finds is closed until further notice. Some collections are evacuated but the precious objects are inaccessibly stored in the archives of the Soprintendenza for the next decades.

Coat of arms of Tarentum. Source: Wikipedia.

When searching for Phalanthos one is stuck with the city’s coat of arms. There, a proud juvenile with a trident and a pretty useless cloth rides a dolphin. Who might that be? Of course, Wikipedia reveals it: it is Taras, son of Poseidon, who drowned in the Tara River. A dolphin allegedly appeared before him when he sacrificed to Poseidon (no idea why he needed a trident and that cloth for that). Afterwards, he was so invigorated that he founded the city of Tarentum. Well, what can we make of that? Tarentum always had its difficulties when it came to telling a myth properly.