20 Years of Portable Antiquities Scheme

translated by Annika Backe

Who owns the past? Who is entitled to an interpretation? Sam Moorhead answers these questions with another question: “What would be the benefit of any kind of scientific discovery if we didn’t inform the general public about it?” Sam is National Finds Adviser for Iron Age (Celtic) and Roman Coins for the Portable Antiquities Scheme at the British Museum. ‘National Finds Adviser’ – the very term is very telling. ‘Adviser’ refers to someone who gives a piece of good advice. This is a perfect description of Sam Moorhead; an adviser who facilitates collaboration between detectorists on the one hand and researchers on the other.

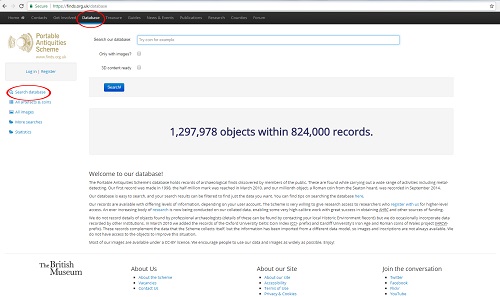

The website of the Portable Antiquities Scheme. Caution! It is addictive! It offers such a wealth of details and search options.

The legal basis

Firstly, however, here are some legal details. ‘Portable Antiquities and Treasure’ is the name of the British Museum’s section where Sam Moorhead works. This name refers to an important English law that constitutes the basis of his work. The Treasure Act came into effect on September 24, 1997, and applies to all items of ‘Treasure’ discovered in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.‘Treasure’ is understood as any object containing at least 10% precious metal, given it is 300 or more years old. A single artefact of precious metal in a group of objects found together makes the whole group ‘Treasure’. Furthermore, hoards of prehistoric base metal objects are also ‘Treasure’. As for gold and silver coins, it requires at least two coins to be found together to constitute ‘Treasure’, whereas for coins made of base metal, the number is 10. Also, finds not covered under the new Act but which would have been Treasure under the old Common law of Treasure Trove also constitute Treasure.

If potential ‘Treasure’ is found, the Act obliges the finder to report the discovery within 14 days to the Coroner in the district in which it was found. The Act allows a museum to acquire Treasure. If a museum expresses interest in acquiring, an inquest is then held by the local Coroner in order to determine whether the find is actually ‘Treasure’. If the result is positive, the state (a museum) has the legal right to acquire the item(s) at a price in line with the market. The market value is established by the independent ‘Treasure Valuation Committee’, which meets at the British Museum four times a year. This committee comprises museologists, archaeologists, a detectorists’ representative and antiquities dealers.

The established purchase price is normally divided between the finder and the land owner, though this might be abated if there is any wrong doing on the part of either party. If no museum wishes to acquire an item of ‘Treasure’, then the find is returned to the landowner and finder who decide its future.

Setting priorities

Selling ‘Treasure’ on the free market? This is likely to make many German, French, or American researchers break out in sweat, but the protagonists of the Portable Antiquities Scheme take a more pragmatic approach. They acknowledge that it is necessary to set priorities, a lesson which has been learnt over time. Some objects are of more national or regional importance than others and there is simply not the funding available to purchase all Treasure. However, because of the Treasure process, all finds are studied, recorded and published on the Portable Antiquities Scheme database for scholars and the general public to consult in the future.

As a matter of fact, many European museums have been housing treasure finds, sometimes for centuries or even longer, without analyzing them or at least publishing an analysis. The British system gives researchers at least the chance to decide, based on professional criteria, exactly which finds are worth trying to raise funds to acquire to enable further study and/or display in a museum. Other countries are known to have finally documented finds that were of no great scientific value, only when funding was unexpectedly made available.

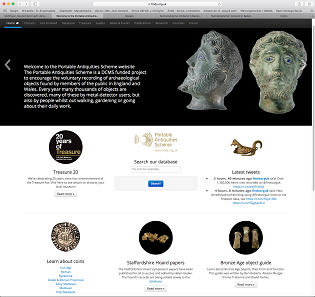

No beauty, but of scientific importance: The finder has entered the coin he had found in July 2017 in the database, with a photo and all the data. It can’t be made accessible to the academic community any quicker.

The Portable Antiquities Scheme, fixing a gap in the law

Any artefacts that do not qualify as ‘Treasure’ do not legally have to be reported, but they are of course still of archaeological importance. When the Treasure Act was being formulated, archaeologists were critical that its scope was limited. Therefore, the Government was minded to establish pilot schemes for the voluntary recording of archaeological finds outside the scope of the Treasure Act. This resulted in the creation of the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS). It aims to make a record of all public finds by reducing inhibitions about reporting and informing the public as to why it is so vital to record even the smallest coin finds to the local Finds Liaison Officer (FLO).

The PAS has been so successful in establishing a practical organizational structure that now it not only registers stray finds but has also become the contact point for the reporting of ‘Treasure’. This is appropriately reflected in the name of the section at the British Museum: ‘Portable Antiquities and Treasure’.

If you want to experience excitement first-hand, talk about the PAS’ success with Sam Moorhead (in the background) and Andrew Brown (in the foreground). Photo: UK.

The practical organizational structure

So how does it look in practice? The PAS maintains 40 local Finds Liaison Officers (abbreviated as FLO). They speak the language of the people, go where both the detectorists and the archaeologists are, organize training for laymen and are as approachable as possible. What if something is actually found? Then you do not have to give Prof. Dr. XY in the State Office for the Preservation of Historical Monuments a call. An e-mail or an SMS to Ben, Sophie or David is often enough for an initial identification. However, finders are urged to bring their finds in for detailed study and recording.

In addition, FLOs recruit on-site volunteers. The 2015 Annual Report listed 259, including 100- who have undergone a basic training that enables them to identify their own finds and enter them into the PAS database.

Basis of the system: the FLO

If you do not know your FLO personally, you will find him or her on the Internet, including his or her telephone number and e-mail address. Local institutions are very much interested in having such an FLO in their team, for the British Museum bears around 85% of the costs as being the one responsible for this project. Only 10-20%, plus overhead costs, has to be financed locally. Furthermore, local institutions are able to draw on the expertise of FLOs to assist in other regional activities beyond PAS.

Funding

This takes us right to the funding issue. The PAS is funded through the British Government’s Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sports (DCMS) grant in aid to the British Museum with local partner contributions. The PAS has also gained grants from other bodies such as the Heritage Lottery Fund which is funding a project, called Past Explorers, aimed at training a large pool of volunteers to help the Scheme record more finds and involve the public in archaeology.

Responsible for overseeing and advising the Scheme is the Portable Antiquities Scheme Advisory Group, where leading archaeologists sit alongside landowners and organizations representing detectorists. This in itself ensures that all parties involved will have their say.

Private vs state

The Portable Antiquities Scheme thus takes account of the fact that no state in the world could compensate the volunteers for their efforts in the service of archeology.

This is where Sam Moorhead, as National Finds Adviser for Iron Age and Roman Coins, and his Deputy, Andrew Brown, come in. They check the database entries and see whether or not they represent an accurate description of the coin. They also help if a FLO or finder are unable to identify a coin, numerous emails bouncing back and forth daily.

Asked what would happen if a lay person was unable to identify an object and entered a wrong description, Sam replies by saying: “You see, the most important thing is that we have the basic data – a photo, technical details and find-spot – so we can then add in the missing information at a later date. In this regard, we do have time on our side.”

This laid-back attitude is likely to make the hair of many a state-funded archaeologist stand on end. How much data could be lost through unskilled people’s interference? To this we can retort by saying: How much data was gained precisely because of all these enthusiastic laymen’s interference.

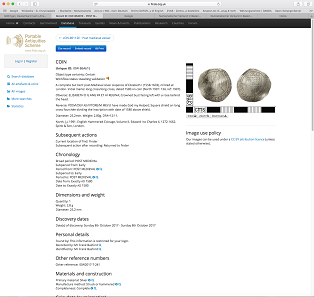

Furthermore, anyone involved with the PAS, whether a finder or recorder, is able to take an interest in the material found. This is because the finds are not published in obscure and expensive academic journals known to initiates only, but on an open database (finds.org.uk). Andrew Brown, Assistant Finds Adviser and Treasure Curator for Iron Age and Roman Coins, provides examples of what can be achieved by using this database.

This the homepage of the database open for everybody to search. Thanks to this, the knowledge gathered within is not a monopoly, but can be evaluated by everyone.

About the benefits of a unique database

If you want to work with the PAS database, you do not only have to search for objects; you can initiate a search on a particular place in the country, or you can set a combined search showing the geographical distribution of particular object types. If you want to download, use and publish the data for your own research, on the other hand, you need official permission. This, however, can be obtained from the PAS, with the provision of a supporting reference. We want to make the data as widely available as possible, but without causing any risk or damage to archaeological sites.

On September 21, 2017, the date Andrew Brown made these screenshots, there were 1,297,978 objects listed in the database.

When I conducted my interview with Sam Moorhead and Andrew Brown on September 21, 2017, among the 1,297,978 objects listed in the PAS database were 417,538 coins.

They included:

Iron Age coins: 45,138;

Roman coins: 256,300;

Greek or Roman provincial coins: 279;

Byzantine coins: 98;

Early Medieval coins:4,387;

Medieval coins:64,236,

Early Modern coins: 46,236;

Modern coins: 474.

Additionally, 3,250 Iron Age and Roman hoard finds are registered in the database.

Britain. Corieltauvi. Quarter stater, 50-40 BC. Lindsey Scyphate Type. Found near Wickenby, Lincolnshire, sold at CNG sale 66 (2004), No 55, for 900 USD.

A renaissance of the object

Sam Moorhead particularly points to one result of this vast number of objects: “Thanks to the PAS, our researchers have begun to develop their theses on the objects proper rather than merely a theoretical model. Just think of the Lindsey Scyphates!”

These are wonderful examples of how one can be misled by one’s own experience or prejudice. 30 or 40 years ago, a highly renowned specialist at the British Museum was presented a scyphate like this as a coin find. The researcher sent the finder home because he did not want to be fooled by such a crude counterfeit. The coin did not correspond to what he was used to seeing from other Iron Age coins. Since then, however, detectorists have found so many scyphates that everyone now knows they are genuine, even if they are manufactured in a somewhat different way than we would expect from Iron Age coinage.

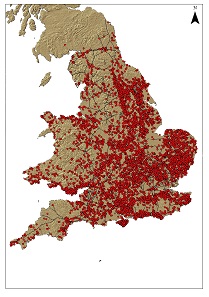

A map of Roman coin finds.

An archaeology-sceptic bon mot claims that in pre-Portable Antiquities Scheme times, distribution maps of particular object types had often shown where people were digging, rather than where the objects were actually used on a national scale.

And now, after the find-spots of 1.3 million objects have been made accessible, the notion of Iron Age and Roman settlement in Britain has been modified significantly: it is now possible to argue that the PAS data can identify around 1,000 Roman sites, which were previously unknown to archaeologists, on the basis of stray finds. Additionally, it has rendered several theories of how the Romans settled Britain obsolete. Thanks to the distribution of finds, you can see from detailed maps that there was not anything like a single overarching Roman monetary economy. Rather, small, regional micro-economies coexisted with different patterns emerging in different parts of the country.

Now it is up to the academics to assimilate this new data and to revise their existing theories. The main reason is that such a crowd-sourced project does not pick and choose the things researchers would deem the most important, but records each and every find and thus changes the picture without academic sampling or prejudice.

A hitherto unpublished denarius of Carausius.

Never label anything as unpublished before checking with the PAS!

The Portable Antiquities Scheme also provides something else: a wealth of Iron Age and Roman coins that were previously unpublished. Sam Moorhead remarks with a grin: “Without wishing to offend anyone, Britain was at the edge of the Roman world after all. If we are constantly finding new variants and types of coins here, what kind of material would be available to us if the countries located at the centre of the ancient world chose a system comparable to the PAS?”

And, needless to add, Andrew Brown contributes with an example taken from the database – one out of many. It is a denarius of Carausius, a type which has been completely unknown up until now.

By the way, many of these new finds are published in The British Numismatic Journal on a yearly basis. And anyone intending to call a coin ‘unpublished’ in a catalogue description should better check with this journal and the PAS Database beforehand, whether it really is.

Twitter screenshot: Since 1996, 1,300,000 objects have been registered in the PAS database.

Criticism of the PAS

As I said, when I finished the interview late in September, there were 1,297,978 objects registered. When I wrote the article 19 days later, the PAS announced on Twitter that object #1,300,000 had been entered in the database.

Sam and Andrew are well aware that there are critics of the Scheme. There are undoubtedly cases when detectorists do not follow guidelines or good practice, and it is known that not all finds are reported. However, given that metal detecting is legal in Britain, the staff of the PAS do their very best to record as much material as possible and to explain to finders why it is so important to record. The fact that so many detectorists have become much more closely interested in their finds, in archaeology and specific research is a testament to the success of the Scheme. Furthermore, university academics are increasingly using the PAS data with over 550 research projects registered on the Scheme’s website. But one should not be complacent as the Scheme cannot be perfect and all have to do all they can to preserve and record our heritage as much as possible.

Outlook

The success of the PAS has of course also been noticed abroad. For very good reason Baden-Wuerttemberg and Hesse have renamed their archaeologists ‘Ansprechpartner’ (German for ‘contact person’). In the Netherlands and in Flanders in Belgium, a system similar to the PAS is being established. In the Netherlands, the name reveals frankly from where the idea was borrowed: ‘Portable Antiquities of the Netherlands’.

In Denmark, a similar database is being set up, and universities in Finland and Norway have expressed their wish to get one, too.

The success’ foundations

It is important to keep one thing in mind, though: The Portable Antiquities Scheme is more than a mere successful organizational model. In Great Britain, several circumstances coincide. The foundation of the scheme is based upon a pragmatic interpretation and application of the law which takes into account the realistic needs of the different stakeholders involved – landowners, finders, archaeologists, museums and researchers. What’s more, British researchers have a tradition of taking the finds of laymen seriously. In the UK, science is not art for art’s sake, but is perceived as a service to the community to which every individual scientist has an obligation. Last but not least, the government’s will to provide the funding for such a project has become a shining beacon for all. A shining beacon providing hope in a sea of conflict between the state, archaeologists, and private citizens that a peaceful coexistence is possible for the benefit of science.

An addictive web page: The Portable Antiquities Scheme website.

How firmly established and widely known the PAS actually is in Great Britain, you can infer from a survey marking its 20th birthday. Whilst in Germany the worst film is elected, in the UK the citizens vote for their favourite treasure.

To view the candidates that applied, click here.

The Frome Hoard came out as the winner. We reported on it in the past, in 2010 and in 2011.

Sam Moorhead recommends the following books to anyone who wants to see how the Portable Antiquities Scheme has influenced the numismatic history of Britain:

A History of Roman Coinage in Britain: Illustrated by finds recorded with the Portable Antiquities Scheme and A History of Medieval Coinage: 1066-1485 and The Beau Street Hoard and The Vale of York Hoard and the Frome Hoard.

And don’t miss this book on the history of hoards!

Further information on Sam Moorhead is available in our Who’s who section.

More of his numismatic publications are available on his Academia site.

And this is the website of the Portable Antiquities of the Netherlands.