The Gold Coinage of Zurich

Thanks to the Reformation, the city of Zurich had put its finances back on their feet. The city council had successfully secularized all the monasteries in the Zurich dominion. Their possessions had not been sold but subjected to the state’s control. According to the figures of modern historians, that brought the state coffers at least 10,000 pounds of silver, which was more money that reformed Zurich could spend on paying its bills alone. That was why it started to hoard its treasures in the sacristy of the Great Minster. Zurich, therefore, had more than enough money at its hands to support the empire’s monetary policy.

After all, the emperor had finally decided to eliminate one of the reasons for the socially motivated riots which occurred after the Reformation. Due to the manipulations more than one ruler performed on his currency out of profit-seeking, the middle tier was deprived of its savings again and again and consequently fought back. To prevent that from happening, the Augsburg Imperial Mint Order from 1551 was introduced.

Zurich. 1/2 krone n. y. (c. 1560) from dies cut by Jakob Stampfer. HMZ 2-1120a. Ex Theodor Grossmann Coll., auction sale Leo Hamburger 1926, lot 223 and Wüthrich Coll., auction sale MMAG 45, 1971, lot 452. Extremely fine to uncirculated. Auction sale Künker 256 (9 October, 2014), lot 6778.

Zurich altruistically supported the mint order of the empire. The contract of newly signed mint master Hans Gutenson reads: “As far as the seigniorage is concerned, Master Hans is exempted from it for the fixed duration of four years, to make him mint coins that are all the better.” Although Gutenson produced coins en masse, Zurich still needed more and hired a second mint master, famous Jakob Stampfer, who – and that was a real technical innovation back then – worked with a roller coining machine.

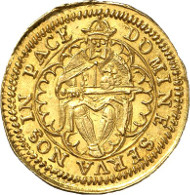

One of these rare gold coins made by Jakob Stampfer will be offered for sale in the upcoming Künker auction sale. It depicts the city’s coat of arms on a double eagle on the obverse, encircled by the text RES PVBLICA TIGVRINA (= Republic of Zurich), and on the reverse a wreath consisting of lilies with the common wording DOMINE SERVA NOS IN PACE (= Lord, preserve us in peace).

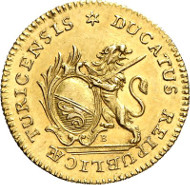

Zurich. Ducat n. y. HMZ 2-1118. Ex Leu 74 (1998), 1974. Very fine to extremely fine. Auction sale Künker 256 (9 October, 2014), lot 6780.

Given the fact that Zurich was a reformed city, this ducat is unbelievable in that it depicts city saints on both sides. The obverse is graced by Charlemagne while the reverse depicts Felix and Regula. Relics of all three saints were kept in the Great Minster.

Zurich. Ducat n. y. HMZ 2-1138c. Ex Leu 80 (2001), 33. Very fine. Auction sale Künker 256 (9 October, 2014), lot 6779.

Charlemagne is depicted on other ducats as well. The exact date of issue of these – as of the aforementioned piece – we do not know. Attempts were made as early as the 18th century to link these coins with a renaissance of the saints.

Zurich. Ducat n. y. HMZ 2-1138a. Ex Leu 74 (1998), 1975. Extremely fine. Auction sale Künker 256 (9 October, 2014), lot 6781.

Thus, Johann Jakob Ulrich, who held the pastorate at the reformed Great Minster, published writings in the 17th century, which he promoted the revival of the saints as first representatives of the Christian faith in Zurich with. His new interpretation probably was met with a certain resonance in Zurich – likewise in numismatic terms.

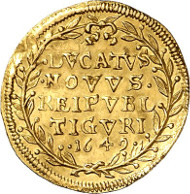

Zurich. Ducat 1649. HMZ 2-1138l. Ex Leu 74 (1998), 1989. Very fine to extremely fine. Auction sale Künker 256 (9 October, 2014), lot 6784.

At any rate, Zurich was very lucky to be able to keep out of the 30 Years’ War. That is why it was spared being devastated, and the bloom accompanying the reconstruction of Germany set in a couple of decades earlier than in other cities. The city fathers of Zurich were happy about receiving several 10,000 gold gulden tax revenues every year.

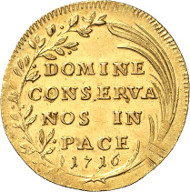

Zurich. Double ducat 1716. HMZ 2-1160f. Ex Wüthrich Coll., auction sale MMAG 45 (1971), 561 and Hegibach Coll., auction sale Hess-Divo 279 (1999), 235. Extremely fine. Auction sale Künker 256 (9 October, 2014), lot 6792.

Between 1672 and 1798, Zurich managed to generate slightly more than 3 million gulden! That is even more impressing in light of the fact that this happened in a time when most other territories were constantly in imminent danger of state bankruptcy – or were even forced to declare it. That made Zurich a sought-after credit granter, humbly approached by figures of the highest social standing – including the emperor himself – for a loan.

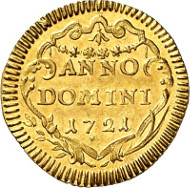

Zurich. 1/4 ducat 1721. HMZ 2-1163l. Ex Hegibach Coll., auction sale Hess-Divo 279 (1999), 329. Extremely fine to uncirculated. Auction sale Künker 256 (9 October, 2014), lot 6794.

Linked with this economic thrive during the 18th century is a multi-faceted and ample gold coinage. It features the heraldic animal of Zurich, i.e. the lion, wielding the sword and holding the coat of arms. The reverse carries the well-known inscription DOMINE CONSERVA NOS IN PACE; the small quarter ducats simply say ANNO DOMINI and state the date.

Zurich. Ducat 1810. HMZ 2-1171a. About uncirculated. Auction sale Künker 256 (9 October, 2014), lot 6797.

The great threshold was the French Revolution which found many supporters in Zurich in the beginning, too. Although the experiment of a united Swiss currency in the Helvetic Republic failed at first and Zurich returned to minting its own coins – gold coins were issued only in 1810 and 1819 –, the Swiss franc was introduced eventually, on 7 May, 1850. That was the end of the gold coins made in Zurich.

You can read an auction preview of auction sale 256 in CoinsWeekly.

The online catalogue of auction sale 256 is available on the Künker website.