50 Years of Celtic Coin Index

by Chris Rudd

How and why was the Celtic Coin Index founded? And what is there to celebrate? Setting up an index of Celtic coins found in Britain was first thought of in 1959 by the archaeologist Professor Sheppard Frere, excavator of Verulamium and author of Britannia (1967), and the numismatist Derek Allen (1910-75), who authored five books on Celtic coins (four of them for the British Museum) and who was the undisputed ‘king of Celtic coins’ for thirty years.

Co-founders of the CCI: Derek Allen, inset, and Sheppard Frere, seen here at Verulamium, 1958, former capital of king Tasciovanos “badger killer”. Photo: Institute of Archaeology, London / British Museum.

Frere and Allen had previously collaborated on a coin gazetteer for Problems of the Iron Age in Southern Britain (1960) a collection of lectures given at a CBA conference held at the Institute of Archaeology, London, in 1958, which was edited by Frere and which contained Allen’s pivotal paper ‘The origins of coinage in Britain: a reappraisal.’

John Sills, researcher on Celtic coins and convenor of Oxford conference, with his die drawings of two Gallo-Belgic Broad Flan gold staters, ABC 1 and 4, c. 175-120 BC. Photo: John Sills.

Philip de Jersey writes: “As a result of his collaboration with Allen on this gazetteer and the discovery that many coins had become separated from their findspots, Frere realised that unlike mass-produced modern coinage, Celtic coins each possessed a unique identity, having been individually struck and with small differences resulting from the position of the dies. It followed that a photographic record would tie each coin to its context – even if its provenance was forgotten in the future – and would also facilitate the detailed study of die-chains. Early in 1959, Allen and Frere thus conceived the idea of the CCI: a record of every British Celtic coin, plus continental Celtic coins found on British soil. Each coin was to be recorded on an 8″ by 5″ index card, with a photograph of obverse and reverse at twice actual size, and information on weight, provenance and other details – a format basically unchanged to the present day” (Ancient British Coins, p. 161).

The first index cards were created by Frere in 1960 and six years later, when he was appointed Professor of Archaeology of the Roman Empire at Oxford, and when he moved from the Institute of Archaeology in London to the Institute of Archaeology in Oxford, he took the CCI with him. It has remained at Oxford ever since, “graduating slowly from what could fairly be described as a broom cupboard through to a modestly-sized office” says Philip.

This shows the cumulative growth of CCI records across five decades. Since 1990 its records have trebled in number, reflecting a marked increase in co-operation between professional archaeology and amateur metal detecting. Source: Chris Rudd.

In 1983 overall responsibility for the Celtic Coin Index was transferred to (Sir) Barry Cunliffe, Professor of European Archaeology at the University of Oxford (1972-2007), who vigorously championed its cause for a quarter of a century and who raised funds for it, year after year, decade after decade. In 1992 he asked Philip de Jersey, author of Coinage in Iron Age Armorica (OUCA 1994), to become keeper of the CCI.

During the sixteen years that Philip managed the CCI he transformed it from a little known file of scribbled index cards to an internationally acclaimed, computerised database, widely used by archaeologists, numismatists, museum curators, collectors, dealers, authors, researchers and students. He also virtually trebled the number of coins recorded by the CCI from 14,000 in 1992 to 40,000 in 2007. This wasn’t because three times more ancient British coins were found or traded during this period; it was because Philip, through his diplomacy, dedication and rapid-response information service – he was often answering as many as twenty different enquiries a day, mostly from metal detectorists – persuaded more people to record and report more coins.

Today the initial recording of provenanced finds is undertaken by PAS finds liaison officers and, in parallel with this, Oxford records mainly unprovenanced coins from dealers’ lists, auction catalogues and the internet. Today the CCI comes under the protective wing of Chris Gosden, Professor of European Archaeology, University of Oxford, and co-editor of Communities and Connections: Essays in Honour of Barry Cunliffe (Oxford 2007) and Rethinking Celtic Art (Oxbow 2008). Moreover, the CCI now houses one of the world’s finest libraries on Celtic numismatics, and at present the total number of CCI records exceeds 50,000 – an appropriate achievement for its 50th anniversary.

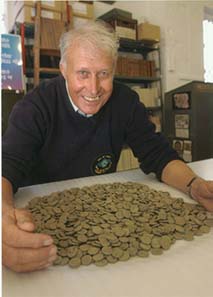

Wickham Market hoard, Suffolk, 2008. 840 gold staters, almost all of Iceni c. 20 BC-AD 20. Found by metdets Michael Dark and Keith Lewis, site dug by archies. Coins valued at GBP 300,000, now in Ipswich Museum. Photo: Judith Plouviez (C) Suffolk County Council Archaeology Service.

For fifty years the Celtic Coin Index at Oxford has quietly rendered a remarkable public service to British archaeology, British numismatics, British museums, British education, British scholarship and British metal detecting. It’s worth noting here that over 80 per cent of the coins recorded by the CCI – that’s four out of every five coins – have been found by metal detectorists since the 1970s. The growth of the CCI testifies to a commensurate increase in co-operation between professional archaeologists and amateur metal detectorists.

Rare linear potin coin of Cantiaci, ABC 159, cast in clay strip-mould c. 80-50 BC, and found by metdet (CCI 05.0218). Type unknown until Thurnham hoard, Kent, 2003, perhaps buried around time of Caesar’s raids in 55 and 54 BC. Hoard found by metdets Peter and Christine Johnson, site dug by archies, coins now in Maidstone Museum. Photo: Peter Johnson / Chris Rudd.

Philip de Jersey says: “The Celtic Coin Index has communicated constructively with all members of the ‘iron age community’ and was helping to foster mutually beneficial relationships with them all, especially archaeologists and metal detectorists, long before Britain’s innovative Portable Antiquities Scheme was pioneered in 1997. Though we may all be pursuing different agendas, I believe that our differences are mostly perceptual rather than actual. What unites us is our respect for the past, our common interest in history and prehistory, and our shared pleasure in handling and studying ancient coins and antiquities. For half a century the Celtic Coin Index has had a huge influence on Britain’s iron age archaeology and numismatics. I estimate that over 300 books, articles, academic papers, lectures and coin catalogues have been helped – sometimes a little, sometimes a lot – by the Celtic Coin Index or its keeper. We need to keep recording iron age coins and we need to continue to demonstrate the value of the CCI. It’s there for you to use, whether in person or via the CCI database: Use it and we won’t lose it.”

Brighstone hoard, Isle of Wight, 2005. 967 silver staters of Durotriges, ABC 2157 and 2160, c. 55-30 BC. Found by 74-year-old Albert Snell, above, and other metdets. Site investigated by archaeologist Frank Basford, coins examined by British Museum and returned to finders and landowner. Photo: (C) Isle of Wight County Press.

Having played a part in restoring the names of eleven pre-Roman rulers over the past twenty years, I think we can fairly claim that the Celtic Coin Index has helped to rewrite the history of late iron age Britain. That fact alone, in my opinion, is enough to justify its place in British archaeology for the next twenty years.

Do you want to check out a coin in the CCI database? Click here.

In occasion of the 50th anniversary of the CCI the Institute of Archaeology at Oxford University will organise a conference. The details on this event you can find here.

For more information on Chris Rudd visit his website.