Under the eyes of Artemis

Abydos, the gate of Asia, and its gold coinage

“From Abydos to that headland bridges were built by the ones appointed. … It is a distance of seven stadiums from Abydos to the opposite shore. But no sooner had the strait been bridged than a great storm came on and cut apart and scattered all their work. The king flew into a rage at this, and he commanded that the Hellespont be struck with three hundred strokes of the whip.” It was Xerxes who gave the order to punish the Hellespont, that rift between Asia Minor and Europe.

The Aegean Sea – die Dardanells were the easiest route for an army to get from Europe to Asia. Photograph: Wikipedia.

Abydos was one of the most important scenes of the Persian advance since the two shores have the shortest distance there. 7 stadiums, i.e. roughly 1.3 kilometres according to modern measurement, is the width of the Hellespont at Abydos.

Hero and Leander

That proximity was thematised already in Antiquity. It is Abydos where the legend of Hero and Leander is located.

William Etty, Hero and Leander. Photograph: Wikipedia.

Leander, a citizen of Abydos, loved Hero, a priestess of Aphrodite from Sestos. Longing to be united with her, he swam though the Hellespont every night. He found his way with the light of a lamp. One night, when a storm doused the lamp, the lover drowned. Hero, who found his corpse the next morning, fell to her death from a cliff.

The history of Abydos

Abydos was founded by the Milesians about 670 B. C. Possibly Thracians lived there long before. Hence, the country was settled ages ago and derived its importance from its strategic position at the crossover between Europe and Asia.

Xerxes lashing the sea. Illustration 1905. Photograph: Wikipedia.

When Xerxes had his bridge built there, Abydos was under Persian domination for a generation. In 514, the city had been conquered. In 480, Xerxes held his military parade there before he went to the Greek mainland only to be utterly defeated. Abydos became free again, but not for long. It fell under the control of Athens, became a member of the Delian League and paid – quite reluctantly, as tradition tells us – since 454/3 annually the high amount of 4 talents (= 24,000 drachms) to Athens.

In 412/11, when the Peloponnesian War reached its end, Abydos utilized the Athenian defeat at Syracuse to break away from the League. It is perhaps that context the magnificent and unique gold stater with an eagle on its obverse and the head of Medusa on its reverse is related to. The gold came from Astyra, a gold mine mentioned several times by ancient writers, Abydos had at its disposal. In Xenophon’s day (426-355), the mines brought considerable yields, whereas Strabo (63 B. C. – A. D. 23) saw them depleted.

In any case, Abydos came under Spanish control soon after and was the most important stronghold of the Spartans in Asia Minor before all areas in Asia Minor fell under Persian control again in 388/7 in the so-called King’s Peace.

A hitherto unknown unique gold stater with a finest cut die

In 334 B. C., Alexander the Great went via Abydos to the Persian Empire. The city was free again which provided a splendid opportunity to celebrate with a new coin emission. A hitherto unique gold stater that will be auctioned off on November 30th, 2010, in Geneva, is probably related to that context.

Abydos. Gold stater, about 330 B. C. 8.60 g. Head of Artemis en face, wearing a wreath, above a polos adorned with acanthus leaves, long earrings, pearl neacklace. Rv. eagle l. standing, in front of it wine branch with grapes. From auction Numismatica Genevensis S.A. 6 (2010), 84. Unique specimen of utmost historical and artistic significance. Estimate: CHF 350,000.

The motif had changed: on the obverse Artemis is depicted now, who received an important cult in Abydos, whereas the reverse shows the eagle that was placed on the older piece on the obverse. The die cutter responsible for that emission truly was a master of his craft. His enchanting, early Hellenistic full face portrait of Artemis wearing a wreath and a polos adorned with acanthus is of highest artistic significance. Despite the small size the depiction nonetheless appears monumental. The model may well have been a local statue of Artemis.

Abydos in Hellenistic and Roman Times

Abydos most probably soon abandoned its own coin minting again. From 328 until 297, it seemed to have minted on behalf of Alexander and his successor Philipp III. After that, Lysimachus utilized the city’s resources and had gold coins issued on his behalf.

After 281, Abydos belonged to the Seleucid Empire, and in 200 Philipp V of Macedonia conquered the city only to destroy it afterwards. When Abydos was incorporated into the empire of the Pergamenes in 188, it was a mere shadow of its former self. In 133, the city became Roman even though the new masters nominally declared it “free”. Abydos is said to have remained faithful to Rome in the Mithridatic War which allegedly provides the background for a last gold emission showing Artemis on the obverse again – this time a bust of the huntress r. – and the eagle on the reverse.

The city’s aftermath

Abydos survived into late Byzantine Times as a customs station. The date of the city’s fall is unknown. There are almost no results from excavations with the former urban region being located in a restricted area today.

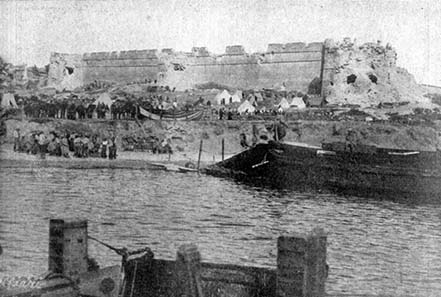

Close by ancient Abydos the Gallipoli Campaign took place in the 20th century. Photograph: Wikipedia.

Since the Gallipoli Campaign, also known as the Çanakkale Wars, from February 19th, 1915, to January 9th, 1916, the region of Abydos is regarded the most vulnerable spot of Turkey.