L. E. Bruun: A Collector in His Time

by Ursula Kampmann on behalf of Stack’s Bowers Galleries

On the occasion of the upcoming auction of the second part of the Bruun Collection, Ursula Kampmann set out again to explore the story of the person behind this collection on behalf of Stack’s. This time, she took a close look at Bruun’s career as a collector. Read on to learn about the coin trade and the world of collecting before the Second World War.

Content

“Every collection is unique” – with these words we began Bruun’s biography in Part I of the L. E. Bruun Collection auctions. It could have been added that collections, however, have characteristics that are linked to the time in which they were created. It is therefore important to delve into the world of collecting at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries in order to understand how Bruun’s coins came together, the obstacles he had to overcome to collect, and the significant achievement that it was to assemble a world-class collection. Only then can we understand why the up-and-comer Lars Emil Bruun was so proud of his coin collection.

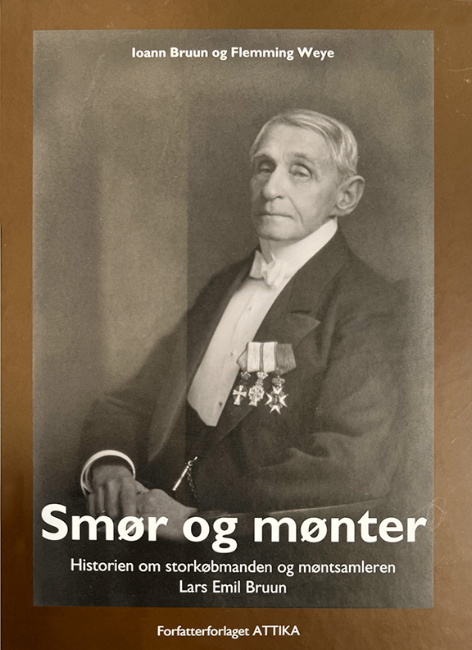

As with my article in the first Bruun auction catalog, for this text we have once again used the book Smør og mønter, which Lars Emil Bruun’s grandson Ioann Bruun and local historian Flemming Weye published together in 2006. The quoted statements come from an interview Bruun gave to the Swedish magazine Hvar 8 Dag. It was published on March 17, 1922, on the occasion of his 70th birthday. The general remarks on the coin trade before World War II are largely the result of my research about the Hamburger & Schlessinger coin dealer dynasty. Other sources are an article on the Frankfurt coin trade published by Erich Cahn in 1981 and an unpublished interview with Herbert A. Cahn that he gave to me a few months before his death in 2002.

Hvar 8 Dag Interviewer: [Mr. Bruun,] how did you start [collecting coins]?

L. E. Bruun: It all began way back in 1859. My uncle died then. He left a few coins and we children got one each. I continued collecting while I was at school, during my apprenticeship, and later when I started my own business. It was at this time that coins became easier to get hold of.

Ioann Bruun og Flemming Weye. Smør og mønter. Historien om storkøbmanden og møntsamleren Lars Emil Bruun. 2006.

The Small Beginnings of a Large Collection

Today we take it for granted that the circulation of money is strictly regulated. This was not always the case. Although it had been prescribed since the Middle Ages which kind of money had to be used in the marketplace, gold and silver coins of stable value from various places and times circulated happily alongside each other at their metal value. This only changed in the course of the 19th century, when nations monopolized the right to mint coins and dictated to their citizens which coins they had to use within the national territory. However, this did not prevent old coins or coins from foreign countries from occasionally appearing in circulation.

The Danish poet Hans Christian Andersen (1805-1875) describes such a case in his fairy tale “The Silver Shilling”, which is well worth reading for numismatists: A Danish shilling from the 18th century makes its way into money in European circulation in the middle of the 19th century. Users no longer knew its value. They think it to be counterfeit and, in bad lighting, pass it off to others, or they punch a hole in it to hang it around a child’s neck as a lucky penny. It’s only a Danish traveler who recognizes its true value, wraps it in paper and keeps it as an antique rarity.

We have to imagine that the young Lars Emil Bruun depended on finding such neglected and outstanding coins in his first years as a collector. There were no coin dealers in the provinces who would sell cheap coins to a young boy. And of course, none of the Copenhagen coin dealers were willing to send an expensive inventory list to a poor apprentice just to encourage his interest in collecting. There was no need to encourage young talent back then. On the contrary, it would have been a stroke of luck for a young collector to find a mentor who would share his knowledge and occasionally gave away a coin.

Lars Emil Bruun had to make do with what he found in circulation or could exchange with friends. For him, an unusual piece was a sensation. The 49 silver and 87 copper coins that he proudly inventoried as a 15-year-old formed a carefully guarded treasure. This must be kept in mind in order to understand the importance that Bruun attached to his collection. It became a measure of the economic and social success of the former apprentice.

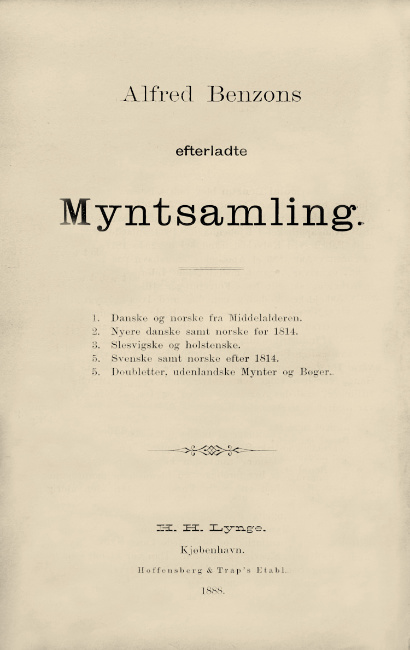

L. E. Bruun: Alfred Benzon, the father of the Benzon brothers, died and left behind a large collection that was sold at about the same time as several other important collections. I also acquired a part of these. … My collection grew because I could afford it…

The Coin Trade Before World War II

Only the move to the Danish capital Copenhagen and his growing financial resources enabled Bruun to build up a serious collection. In the 1880s Copenhagen had an active numismatic scene featuring auction houses and coin dealers but could of course not compete with the numismatic centers such as London, Frankfurt, Vienna or Paris.

The coin trade at that time was different from what we know today. Coin shows, for example, did not exist. Auctions were a rare event and reserved for important collections. So the collector’s most important port of call was the local coin dealer. Mark Salton’s description of his father’s business premises gives us an idea of what this might have looked like:

“The office on the first floor, “parterre” as it was called, looked like it was out of a Charles Dickens novel. It consisted of a flight of high-ceiling rooms of varied sizes, mostly lined with book cases, numerous large and small wooden coin cabinets and several safes. The felt-covered tables, surmounted by green lamp shades, were strategically placed near the windows and cluttered with paper work, coin trays, catalogues, more books and the like. The exception was the reception room; here in impressive, somewhat formal surroundings, a library in fine bindings was neatly kept in two large glass-enclosed ebony book cases for use by clients.”

The customer only came as far as the reception room. There he was asked about his wishes. Once he had stated his areas of interest, the coin dealer hurried to the back to put together a corresponding selection of coins on a tray. The customer sat down with the dealer and looked at the offering. If he needed a book, it would have been brought to him from the reference library that was available in the visitor’s room.

Catalogue de la Collection de Monnaies de feu Christian Jürgensen Thomsen. Seconde Partie: Les Monnaies du Moyen-Age. Tome III. Copenhagen 1876.

Sometimes a client didn’t come to buy coins, but to consult the latest auction catalogues, which a dealer had subscribed to at great expense. Before World War II, auction catalogues were a precious commodity. They were only printed in small runs and were sold for a heavy fee. A coin dealer was happy to pay the cost because this was the way to get the orders from his customers. After all, the auction catalogues contained only a few illustrations, so that anyone who could not view the coins in person had to rely on the help of representatives. Bruun, too, looked at the catalogues at the Copenhagen coin dealers’ shops at the beginning of his collecting career and gave them his orders. When he had become rich, he could afford to order auction catalogues himself and to attend the auction sales in person.

Nevertheless, a large proportion of Bruun’s coins do not come from auctions, but from the vaults of coin dealers. Therefore, the provenance of the pieces is often not ascertainable. Bruun was often on business trips and combined these with visits to local coin dealers. The most important market for canned butter was Great Britain. How lucky for the collector Bruun! Since the French Revolution, London had been the center of the European art trade and thus of the coin trade.

The vaults of the major coin dealers were treasure troves for every collector at the time. They often contained great rarities at fixed prices. Herbert Cahn said that local collectors usually came to the premises of Münzhandlung Basel once a week to browse through the latest purchases. The Cahn brothers did better business with out-of-town customers, as they often bought larger contingents of coins. It was particularly important to find out about their collecting area and to record it in an extensive card file. Whenever the Cahns bought a new collection, they consulted their customer card file and sent out offers.

The fact that Bruun also received and wanted to receive such offers from all over Europe is evidenced by a letter he wrote in English to the coin and bookseller W. S. Lincoln on 16 July 1886:

“I have several times bought coins from Saint Canute 1080-1086 – in England and when I called on you in London 3 weeks ago, I bought one of you. If you have some more of these coins you can send me them, but I can not afford to pay more than about 10 sh. per piece for them. If you get some other Danish coins or such as you suppose to be Danish, it would be a good pace [sic – intended wording not known] if you sent me a sketch of them and the price on a letter post card. It cost [sic] only a penny.”

Lincoln was asked to send sketches of the coins he wanted to offer. Other coin dealers sent plaster casts or pencil rubbings. Photographs were not used, as they were far too expensive to depict individual coins.

When did Lars Emil Bruun start collecting on a large scale? He gives us a clue: In his interview we read that he acquired part of the collection of Alfred Nicolai Benzon (1823-1884). Benzon was the founder of the first pharmaceutical company in Denmark, and it made him one of the richest men in the country. He also became known beyond the borders as an authority on pharmacy. The Natusan ointment he invented, for example, is still produced today by Johnson & Johnson.

Benzon’s coin collection comprised more than 11,000 objects. It was sold in five auctions between 1885 and 1888, which – as was common in Denmark at the time – were conducted not by a coin dealer but by a lawyer. 1885 was the year in which Bruun’s financial circumstances changed fundamentally. That year he also became a founding member of the Coin Collectors’ Society of Copenhagen. Bruun therefore began to buy coins on a large scale as soon as he could afford it financially. His first purchases were so large that other collectors considered him worthy of joining the group of founding members of the Coin Collectors’ Society of Copenhagen.

L. E. Bruun: I don’t leave … coin auctions to anyone…!

Auction Sales

And that brings us to another central source from which the coins in the Bruun collection originate: the auctions. Back then, they were not the rule, but the exception. Herbert Cahn said in his interview that a small group of professionals gathered for them in the company’s premises. He explained that the catalogues often stated the first day of the auction only, because nobody knew how long an auction would take. Everything lasted much longer than today – sometimes an auction sale continued several days. Cahn described the auctions of Münzhandlung Basel as social events. All bidders gathered around a huge table. Each lot went from hand to hand before the auctioneer asked if anyone wanted to bid on it. Bidding fights were very rare back then. And often, coins didn’t even sell.

Taking part in an auction was therefore a time-consuming affair. Very few collectors could afford to travel and attend the auction for just a few coins. Bruun was the great exception. He wanted to view his coins before buying them. Perhaps he also enjoyed discussing them with fellow collectors and numismatists. His extensive language skills were useful. As we know from his correspondence with coin dealers, he spoke French, English and Spanish in addition to his mother tongue; he could even speak German, although he was reluctant to travel to Germany. Germany remained enemy territory for him after Prussia and Austria annexed large parts of his native country after the German-Danish War of 1864. That is why Bruun did not buy any German coins, except of course those that he considered to be Danish, namely the coins from Schleswig and Holstein.

But Germany was an important hub of the coin trade at that time. No serious collector could afford to ignore the German auction houses. That is why Bruun would occasionally commission a dealer when a major auction took place on German soil. Let’s look at one example. Auctioneer H. Bukowski from Stockholm attended the sale of the Christian Hammer collection sold by J. M. Heberle in Cologne on behalf of Bruun. We learn from a letter Bruun wrote to him on 15 September 1891 about the great freedoms he gave him concerning his commissions:

I am sending you this letter regarding the auction lot numbers registered in the attached list – as last time, I have not fixed any limit, but leave it to you to buy for me what is available at reasonable prices. You will certainly remember that I only want well-preserved specimens, as I do not want worn pieces in my collection.

As for the Danish coins, I have not given any prices here either, but I would particularly like to have the lot numbers marked in red, so I ask you to buy these for me, even if the price is a little higher. Please send me a copy of the catalogue with the annotated prices after the auction.

The list of Bruun’s preferences has survived. It features 233 lot numbers that he was willing to buy for a reasonable price, as well as 20 Danish coins marked in red that he really wanted.

Particularly interesting is Bruun’s request to get an additional copy of the catalogue with the annotated prices. At this point we get to know him as a price-conscious buyer who wanted to use current auction results as an argument in sales negotiations.

Bruun liked to buy at auctions and did so frequently. You will find at the end of the Stack’s Bowers auction catalogues of the Bruun Collection a detailed list of all those famous collections from which Bruun acquired coins. We may assume that Bruun monitored the entire European auction market and bid whenever he spotted interesting coins from his areas of collecting.

L. E. Bruun: To build a large coin collection, you will need three things: great diligence, significant capital and luck.

Hvar 8 Dag Interviewer: What do you understand by luck?

L. E. Bruun: If all the old people whose collections I bought from in the 1880s were young then, I would never have gotten their coins. And there will always be coins I can acquire. If I live another 20 years and keep my interest, and my financial circumstances do not change, it would be strange if I didn’t find more coins.

What Role did the Copenhagen Numismatic Society Play Concerning the Purchase of Coins?

Bruun supported many numismatic societies with his contributions. He was a member of the Svenska Numismatiska Föreningen, the American Numismatic Society, and the Royal Numismatic Society. Incidentally, along with several citizens of the United States, Bruun was the only non-British corresponding member of the illustrious British Numismatic Society. The most important for him was of course the Coin Collectors’ Society of Copenhagen of 1885 and its successor society.

Although lectures formed part of the regular meetings of the associations, Bruun attended them probably for another reason. Association meetings were a good opportunity to buy coins. Herbert Cahn said that he and his brother Erich regularly attended the meetings of the various coin clubs to offer their latest acquisitions. We can assume that the Copenhagen meetings also attracted all those who had coins to sell.

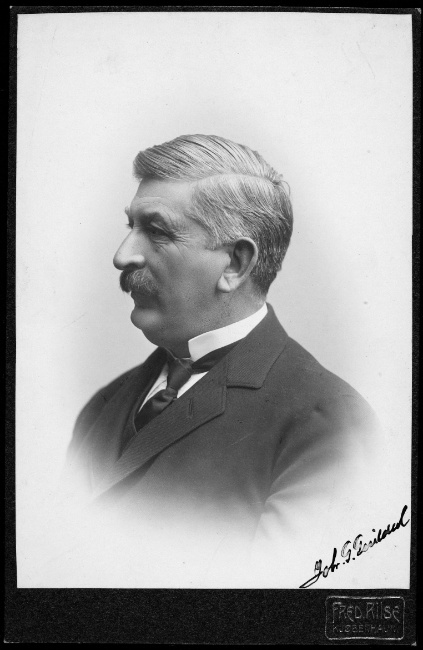

The trade between members was particularly important. Everyone occasionally sold duplicates or pieces that no longer fit into their collection. Now and then, even complete collections were offered. We know that Bruun was actively involved in this. For example, in 1918 he acquired the collection of Johan Peter Samuel Goldschmidt (1855-1920). Goldschmidt, who originated from a prominent Jewish dynasty of bankers and had changed his name to Guildal in 1906, had also been a founding member of the Copenhagen Society.

Acquisitions like this explain the fact that there are many coins in the Bruun collection which were sold in auctions in which Bruun could not have personally bid, either because he was too young when the auction took place, or perhaps because he could not have raised the money at that moment of his career.

The Guildal collection is a good example for that, because it included another important collection. We are talking about that of Major Carl Thorvald Jørgensen (1819-1902), an important numismatist and one of Denmark’s most famous military officers. Jørgensen – affectionately known as “the old pioneer” by his subordinates – retired from the service in 1884 as a major general. He then occupied himself with acquiring materials for his fundamental monograph on Danish monetary history. It is entitled Beskrivelse over Danske Mønter 1448-1888 and is based largely on his own coin collection. The twelve folio volumes of material that Jørgensen collected for it are still available to researchers today in the National Museum in Copenhagen.

J.G. Guildal. (Danish Royal Library).

Jørgensen sold his collection to Guildal shortly before his death in 1901. He could have sold it to Bruun as well. It is remarkable that he did not do so. We know that Bruun kept selling duplicates and parts of his collection until 1914, presumably to use the proceeds to finance other purchases. We know that he did excellent business as a manufacturer of canned butter, being known for delivering cheaper than his competitors. His profits over the decades as well as during the first world war undoubtedly helped with the acquisition of the August K. Krautwald collection in the middle of the war, in 1916, and then the Guildal collection in 1918. In 1922, shortly before his death, he crowned his collecting career with the acquisition of the Bille-Brahe (i.e. the Countship of Brahesminde) Collection.

Bruun sold the duplicates generated by the Guildal collection acquisition, not through an auction house, but privately – probably during the coin club meetings – to collectors.

Why Did Bruun Collect?

The motivation that drives a collector is as individual as his collection. It is nice that Bruun himself tells us in his interview what his coins meant to him:

The beauty of coin collecting is that it is soothing. When you are feeling sad or anxious, you look at your coins, study them again, and ponder the many unresolved problems they raise. Many people who are solely concerned with their business lack such a distraction. It would be as if I were thinking only about butter until I literally fell off my chair.

Business magnate Bruun did not want to be defined solely by his business. He saw himself as a numismatist and a historian. In the same interview, he describes the problems that mattered to him:

“Where does a coin come from and how should it be classified? Danish coins can be said to have been the worst coins in the world from the murder of Erik Klipping until the reign of Queen Margaret. Every year, five mints struck a new type of coin – that is, five different coins per year. Only the current coin could be used to pay the tax. To do this, two old coins had to be exchanged for a new one, which tempted the king to mint inferior coins. King Christopher II, who died in 1332, minted coins made of pure copper. The end result is extremely crude and plain. Some coins, for example, have only an “A” on one side and a “P” on the other. But which one comes from Roskilde and which one from Ribe?”

For Bruun, numismatics was a bridge to Denmark’s glorious past: “The really old coins are often the only contemporary evidence of their era. Without them, one might think that everything written about our earliest kings was just made up.”

Hvar 8 Dag Interviewer: Is it expensive to collect coins?

L. E. Bruun: I own coins for which I have paid up to 5,000 kroner a piece. If I had collected paintings instead, I could have bought enough paintings to cover many walls for the money I spent on coins.

Limited or Unlimited Resources?

Money always played an important role for Bruun, who grew up in poverty. He kept a close eye on the price a coin was fetching and undoubtedly knew how to use his knowledge to haggle with coin dealers. On the other hand, Bruun was quite prepared to spend large amounts of money if he really wanted something. For example, he bought what he considered the highlight of his collection from the Hyman Montagu (1844-1895) Collection, a significant part of which was auctioned in November 1895, for 8 pounds. He was still raving about this coin shortly before his death.

L. E. Bruun: I own the oldest Danish coin. I travelled to London especially for this coin. I was sitting here in the living room reading when I remembered what I had read 20 years ago by Worsaae [Jens Jacob Asmussen Worsaae (1821-1885), Danish archaeologist who coined the term Viking Age]. I travelled to England without anyone knowing about it and bought it for 8 pounds! It is from Berse. He had it minted during a military campaign in England in 870 AD.

Bruun believed he could read the inscription Bagsecg on the coin. Therefore, he wanted to attribute it to a rather mysterious figure in Danish-English history, whom he knew as Berse. Today, we speak of Bagsecg. This Bagsecg was a Danish Viking chieftain who fell in the Battle of Ashdown. In the nationalist historiography of the 19th century, Ashdown was considered a decisive victory for Alfred the Great, who was revered as one of the founding heroes of England. Important monuments were associated with the event. Bagsecg is said to have been buried in the chambered tomb, now proven to be Neolithic, which became known as Wayland’s Smithy. The White Horse of Uffington was even thought to be Alfred’s victory monument.

Bruun was thrilled to hold a testimony to this event in his hands. He paid an almost insanely high price for the piece. But he made a mistake. He followed his desires and read what he wanted to read. Today we know that Bagsecg did not have any coins minted. There are doubts that he even existed. But for Bruun, Bagsecg’s penny was the showpiece of his collection, which he often showed off when telling his version of Danish history.

L. E. Bruun: I had the best collection of Swedish coins, except for the royal collection. But in 1914 I was persuaded to sell them in Frankfurt. I regret that.

Selling Parts of his Collection

Bruun was constantly buying coins, and over the years he sold duplicates from his collections. We can assume that he used the proceeds to purchase other pieces. On May 22, 1894, he sold 28 duplicates through the Copenhagen auctioneer Christian Hee. Four years later – on May 16, 1898 – his duplicates, which were again offered at Christian Hee, filled an entire auction sale with 673 lots. In 1901, Bruun decided to offer his duplicates anonymously: the Copenhagen auctioneer H. Carstensen auctioned the 337 lots on March 21.

After that, he stopped selling anything at public auction for a long time. It was not until 1914 that Bruun sold an entire part of his collection: his Swedish coins. He considered this part of his collection to be the most important collection of Swedish coins except for the royal collection in Stockholm. We should ask ourselves why Bruun, a declared enemy of all Germans, decided to entrust his coins to German coin dealers of all people. He choose the well-known Adolph Hess Nachf. coin dealership in Frankfurt, founded in 1871, as auctioneer.

Then, this numismatic auction house, which had been run by Louis Hamburger and James Belmonte since 1893, enjoyed an excellent reputation due to the scholarly quality of its auction catalogues. This is why the most important European collectors consigned to Hess. The fact that Adolph Hess Nachf. had a large customer base for Swedish coins was proven by the sale of the Freybourg collection in 1910 and the Paul Friedrich Bratring collection in 1912. For Bruun, it was therefore a question of prestige and economy to rely on a German rather than a domestic auction house to auction off his Swedish coins.

Adolph Hess Nachfolger. Auktion 19. Mai 1914 in Frankfurt a. M. Sammlung des Herrn L. E. Bruun in Kopenhagen. Schwedische Münzen I. Teil: Vom Mittelalter bis Gustav Adolph

After the auction, however, things looked differently. The first part of the collection – from the Middle Ages to Gustav Adolph – was auctioned on May 18, 1914 for a satisfactory 69,000 marks. Then Gavrilo Princip shot Franz Ferdinand, the heir to Emperor Franz Joseph, in Sarajevo, thus triggering the First World War. Adolph Hess Nachf. cancelled the auction of the second part of the Bruun collection – from Christina to the present – planned for October 26, 1914. Bruun thus experienced every collector’s nightmare: he was left with half a collection. Undoubtedly frustrated, he decided to sell his remaining Swedish coins privately. Israël Berghman (1864-1945), a Swedish wholesale merchant, bought them for 65,000 kroner and sold them to the Amsterdam coin dealer Jacques Schulman in 1921. Schulman in turn sold the ensemble to Virgil Brand. Everyone – except Bruun – made a good profit.

This was humiliating for the business magnate in several ways: just before the outbreak of war, he had gone against his long-held convictions and entrusted his coins to the enemy. He had also made a bad business decision by hastily selling the coins that had not been auctioned to Israël Berghman. Last but not least, the profits he made during the First World War would have made any sale unnecessary. Bruun now had enough money to buy up entire collections himself. But collections of this quality were extremely rare. All of this must have annoyed the businessman. We can still sense this anger in the derisive words he used to describe Virgil Brand in 1920: “The man looked like a little German innkeeper, and I believe that his inner mind corresponds to his outer appearance. … He hardly knows what he has, but keeps a fairly accurate description of what he buys in a log which he showed to me, and judging by it he must certainly have bought many duplicates.”

L. E. Bruun: By the way, I am planning to catalogue my coin collection. I have already made one of the Swedish coins, but I lost money on it – 1000 copies featuring 80 plates cost a lot.

Bruun was perhaps unwilling to admit that he himself was responsible for all these bad decisions. In an interview in 1922, he claimed that he had been “persuaded” to sell his Swedish coins in Frankfurt. We can see that this was not the case because Hamburger and Belmonte were not prepared to fulfill their customer’s extravagant wishes. Bruun had to finance the 80 collotype plates he requested to illustrate the catalogue all by himself; additionally Hess charged him a premium to print the unusually high print run of 1,000 copies. Nevertheless, the catalogues of the Swedish coins from the Bruun collection are extremely rare today, which is no wonder, given the historical circumstances.

L. E. Bruun: So I became the owner of the largest collection of Danish and Norwegian coins. Then I started with Swedish coins and in the 1890s with English coins. … I have the best collection of English coins except for the British Museum and a really good collection of French coins.

On the occasion of Lars Emil Bruun’s business’ 25th anniversary, his employees had a medal minted as a tribute to their celebrated employer. The medal was accompanied by a beautiful, calligraphic letter of congratulations.

The Largest Collection of Danish Coins

Bruun was a child of his time. This means that his nation played a central role for him – also and especially in his work as a collector. As a proud Dane, Lars Emil Bruun naturally collected Danish coins, and for him that included everything that Denmark had controlled in whole or in part at any point in history. That is why he was interested in the English Middle Ages, when Sven Forkbeard and Canute the Great founded a Danish Viking kingdom on English soil. That is why Norway and Sweden were important to him, because both countries had long been under Danish rule. Even the duchies of Holstein and Schleswig (now chiefly in Germany) fell within his collecting area, even though Bruun did not actually buy German coins. But for him Holstein and Schleswig were not German, but Danish. It is precisely at this point that the political aspect of his collection becomes apparent: with the coins he documented that these territories were wrongfully taken away from the Danes after the German-Danish War.

Shortly before his death, Lars Emil Bruun could proudly claim that he owned the largest collection of Danish and Norwegian coins. It essentially includes the coins of all Danish kings from Svend Tveskæg to Cnut the Great and to Christian VIII. A particularly large number of pieces date back to the time of Christian IV (1588-1648), including numerous heavy gold coins. His reign was thought to be the heyday of Denmark, when Christian IV tried to establish a Danish imperium conquering parts of Germany during the Thirty Year’s War.

The Swedish part of the coin collection was also extensive and spanned the period from the first pennies minted in Sigtuna shortly before the turn of the millennium Gustav V, who ruled Sweden during the latter part of Bruun’s life.

His collection of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein was also impressive, although not as high-caliber as the collection of Danish and Swedish coins.

Lars Emil Bruun also owned an extensive collection of medals showing celebrities and focusing of course on Danish royals and public figures.

Bruun had a large, fireproof safe installed in his residence at Havnegade 29 for this numismatic treasure. But such a safe was not only located in Copenhagen. The most modern security technology also protected the valuable collection in rural Ordrup. On the occasion of Bruun’s 70th birthday in 1922, a journalist described the numismatic paradise of the business magnate as follows: “L. E. Bruun’s ‘world’ is covered with old, rare coins; it shines in his universe like snow-white silver, amber gold and green. What looks like grass is actually patina. Five massive steel cabinets with complicated locking mechanisms stand in the middle of the [building] on Anettevej. In such a simple and quiet environment as Anettevej in Ordrup.”

And even that was not enough for Bruun: his safe was built “with an alarm signal connected to the lock. And woe betide the guest who does not raise his hands when I point my gun at him. It would of course be unfortunate if he lost his life, but what was he doing here?” says Bruun. The journalist can’t help but admire the safe: “One of the cabinets opens. Two Chinese towers made of hundreds of narrow shelves appear – a prime example of ingenuity and craftsmanship. L. E. Bruun pulls out one of the drawers: old coins with strange pictures, profiles and inscriptions.”

A year before his death, Bruun had reached the zenith of his collecting career with the acquisition of the Bille-Brahe (Countship of Brahesminde) Collection. He owned the best collection of Danish and Norwegian coins, except for that of the Danish state, of course. He was proud that his collection of English medieval coins was second only to that in the British Museum.

For Lars Emil Bruun, collecting was not just a matter of prestige, but also a duty that led to the incredible will that ensured that the collection remained under lock and key for a century.