Münster, Osnabrück, Passau and the Counts of Lamberg

by Ursula Kampmann

On 3 July 2025, Künker will auction the third part of the collection of a German manufacturer and history enthusiast. The auction combines coins and medals from several fields: Münster, Osnabrück, Fugger, Leuchtenberg and Passau. Are you wondering what the connection between these regions is?

Content

At first glance, they did not have much in common except for the fact that they all accepted the emperor as their sovereign. However, this is no minor fact – it is precisely what turned imperial territories into squares on an enormous board game, used by the nobility to plan their family’s ascent through their sons’ careers. The best strategy was to occupy as many squares as possible with relatives, sons-in-law or fathers-in-law, and allies. This made it possible to form alliances and advance one’s interests. After all, it was often not high politics that drove history forward, but a combination of various interests.

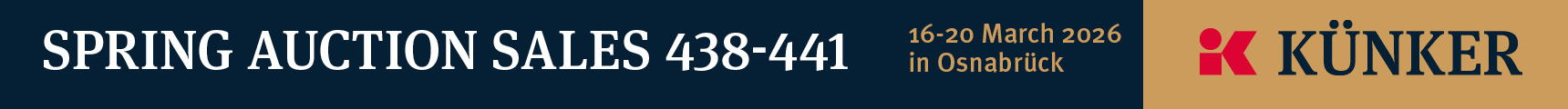

Portrait of Johann Maximilian of Lamberg. Hall of Peace / Münster city hall and his signature on the Osnabrück treaty of the Peace of Westphalia.

Johann Maximilian of Lamberg

Let us begin our journey through time and space in Münster, specifically in the Hall of Peace in Münster’s city hall. Portraits of the individuals who played a significant role in concluding the Peace of Westphalia are displayed here. Looking down from a prominent position, we see a man whom few people have ever heard of: Johann Maximilian, Count of Lamberg, Plenipotentiary of the Holy Imperial Majesty. Well, at least that is what the legend of the portrait says. Plenipotentiary? Hardly anyone will be familiar with this term. It is a combination of the Latin words for “full” and “power”. This means that Johann Maximilian of Lamberg had the authority to sign treaties on behalf of the emperor. And he actually did. It was his signature, placed just below that of Queen Christina of Sweden, that turned the Peace of Westphalia into legal reality from the imperial side.

But who was this man, whom the emperor trusted to such an extent that he was permitted to sign such an important treaty on his behalf?

Johann Maximilian of Lamberg was born in 1608 as the son of a Freiherr, a title similar to that of a baron in rank. While not at the top of the aristocracy, this position came with opportunities. His father let his son study and financed a Grand Tour, an important educational voyage through Europe taken by young men of the time to make connections and learn courtly behavior as well as foreign languages. This qualified Johann Maximilian for an administrative career at a princely court. After that, he got lucky: Emperor Ferdinand II took notice of him and accepted him into his service. Johann Maximilian was intelligent and good with figures. The Emperor acknowledged this and appointed Johann Maximilian as financial administrator to his son, the future Emperor Ferdinand III.

It appears that Johann Maximilian was very good at his job. He won the trust of three emperors: Ferdinand II, Ferdinand III and, because the latter appointed Johann Maximilian as tutor to his son, Leopold I.

Johann Maximilian had a picture perfect career, becoming one of the top diplomats of the Habsburgs. This also came with marrying a wealthy heiress from an excellent family and being elevated to the hereditary rank of imperial count. The emphasis is on “hereditary”. It was through him that the Lamberg dynasty rose to the upper echelons of the empire.

Münster. 1648 gold medal of 10 ducats by E. Ketteler, commemorating the Peace of Westphalia. 34.70g. Very rare. Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 10,000 euros. From Künker auction 424 (3 July 2025), No. 556.

This is why Johann Maximilian traveled to Westphalia to negotiate an end to the Thirty Years’ War. He shared this responsibility with a relative by marriage: Count Maximilian von und zu Trauttmansdorff-Weinsberg was the grandfather of Johann Maximilian’s eldest son and heir’s wife. In this way, the emperor ensured that both diplomates would cooperate. They shared their duties without jealously. Trauttmansdorff-Weinsberg operated in Münster, and Lamberg in Osnabrück.

What can we learn about this process on medals? Nothing! They remain silent about the diplomats, as illustrated by this Münster gold medal from auction 424. The circumscription suggests that it was only emperors and kings who were needed to establish the golden peace through a handshake. Countless images and pamphlets followed the same narrative. While the rulers certainly laid down guidelines, capable employees were needed for the practical implementation.

And these employees obviously did not negotiate for altruistic reasons. They received their reward once they had concluded a favorable treaty. For John Maximilian, the Peace of Westphalia came with the Order of the Golden Fleece and imperial protection for his sons.

Johann Philipp of Lamberg. 1698 ducat as Bishop of Passau, minted in Augsburg. Very rare. Extremely fine. Estimate: 5,000 euros. From Künker auction 424 (3 July 2025), No. 640.

Johann Philipp of Lamberg

Using the example of Johann Philipp of Lamberg, the fourth and youngest son of Johann Maximilian born in 1651 (or 1652), we would like to demonstrate what this meant in concrete terms. It is important to keep in mind that a nobleman’s chances at success decreased with his position in the line of succession. A fourth son could not hope for much. And yet – thanks to his father’s connections and his excellent planning – Johann Philipp rose to become one of the leading politicians of his time.

Johann Maximilian kept two options open for this son: the young man could either enter the diplomatic service or pursue a career in the church. Johann Philipp thus received the education required to become a diplomat. He studied law in Vienna, Steyr and Passau. He then completed his Grand Tour, during which he received his doctorate at the University of Siena. This earned him a position as imperial counsel in 1676. Johann Philipp proved himself to be a capable diplomat as well and became one of the leading figures in his field.

At the same time, Johann Maximilian secured all the church offices for his youngest son that he could hold without the higher ordinations that offered the possibility of becoming a bishop. Johann Philipp became canon in Passau at the age of eleven, canon in Olmütz at the age of sixteen and canon in Salzburg at the age of twenty-three.

So when the Passau bishop passed away on 16 March 1689, all members of the Lamberg family made use of their connections. For one, they approached the emperor. And they also approached the Bavarian elector (who at this point believed that he could use the support of the family to strengthen his claims to the Spanish succession). It is very likely that many more people were involved. We simply do not know anything more about it today. In any case, the initially reluctant cathedral chapter finally elected Johann Philipp as the new bishop on 24 May 1689. He was confirmed by the Pope on 11 May 1690 and consecrated as a bishop on 14 May 1690.

Johann Philipp of Lamberg. 1706 taler, Regensburg, as cardinal. Only 800 specimens minted. About extremely fine. Estimate: 5,000 euros. From Künker auction 424 (3 July 2025), No. 649.

As Prince-Bishop of Passau, Johann Philipp had the right to mint coins. A small selection of the coins produced on his behalf are on offer in auction 424. By the way, these pieces were no longer made in Passau as the mint there was closed in 1682. It was more cost-effective for Johann Philipp to place orders with the well-established mints in Augsburg and Regensburg than to have his own mint. The Regensburg mint in particular came with logistical advantages. After all, Johann Philipp of Lamberg was frequently in Regensburg to represent the emperor at the Perpetual Diet.

Johann Philipp of Lamberg. Gilded silver medal as Bishop of Passau, 1698. Extremely rare. Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 2,000 euros. From Künker auction 424 (3 July 2025), No. 654.

A reminder of these diplomatic missions is an interesting group of medals created on behalf of Johann Philipp of Lamberg as diplomatic gifts. They all show the portrait of Johann Philipp in full regalia on the obverse. The reverse features a putto leading a mighty lion on a thin chain. The translation of the circumscription reads: Calm power accomplishes what violent [power] cannot.

In his book on the numismatic issues of Passau bishops, Hans-Jörg Kellner attempts to link this motif to a particular event. The options are a treaty with Bavaria (lion!) and an agreement with the citizens of Passau. However, both theories are refuted by the fact that Johann Philipp kept the reverse almost unchanged throughout this reign: the first medal of this type was created in 1691, the last in 1705.

Therefore, it is much more likely that these medals are a testament to how Johann Philipp saw himself. And what would be more fitting for a diplomat than praising the art of gentle persuasion?

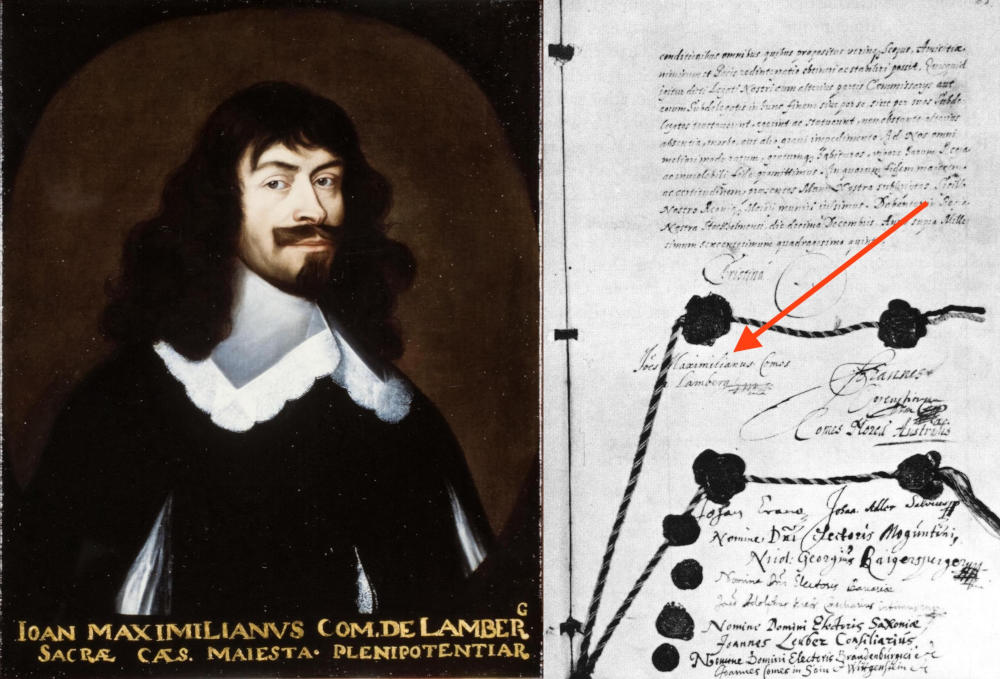

Entry of the Passau prince-bishop in Regensburg after he was elevated to the rank of a cardinal on 1 December 1701. Graphic from the collection “Klebeband Nr. 15 der Fürstlich Waldeckschen Hofbibliothek Arolsen”, cc-by-sa 3.0DE

Cardinal Johann Philipp of Lamberg

The two careers pursued by Johann Philipp of Lamberg were not exclusive; they rather complemented each other. Leopold I held his envoy in high esteem, who repeatedly represented him at the Perpetual Diet in Regensburg – he valued him so much that he proposed to the Pope that Lamberg be elevated to the rank of a cardinal. Of course, his reasons were not purely altruistic. A cardinal had a number of ceremonial privileges that an experienced diplomat could skillfully use to strengthen his position, ultimately to the benefit of his sovereign. So it was a win-win situation for patron and protégé.

The newly appointed cardinal made a strong impression on the diplomatic world when he entered Regensburg for the first time after being conferred this high ecclesiastical office: on 1 December 1701, the procession took place in beautiful weather – no coincidence, as they had deliberately waited until the conditions were just right. Johann Philipp sat in a carriage adorned with gold and velvet. He was accompanied by 266 members of his court wearing elaborate liveries. This demonstration of Passau’s (and the emperor’s) wealth was extremely expensive. The liveries of the servants alone cost a staggering 16,198 guldens and 55 kreuzers. For comparison: Passau had a tax income from its citizens of 2,500 guldens.

Johann Philipp only saw his own bishopric on rare occasions. But this did not stop him from commissioning expensive new building projects. He completed the interior of Passau Cathedral, had a new residence built, founded cities such as Philippsreut and took care of the education of priests in his diocese.

Of course, he also defended his seat when the War of the Spanish Succession broke out in 1701. Passau was caught between the fronts. Austria fought Bavaria and took prophylactic measures by occupying the strategically important city of Passau. However, thanks to his good relationship with Max Emanuel, Johann Philipp managed to prevent his troops from taking Passau by storm.

Johann Philipp of Lamberg. Gold medal of 18 ducats, 1705. Extremely rare. Extremely fine. Estimate: 7,500 euros. From Künker auction 424 (3 July 2025), No. 655.

However, these political maneuvers did not go down well at the Vienna court. In addition, Leopold I, the most important patron of the Lamberg dynasty, passed away in 1705. Johann Philipp used the coronation celebrations of his successor Joseph I to launch a charm offensive. After all, such festivities were a perfect opportunity to visit old allies and friends to give them diplomatic gifts. Thus, Johann Philipp had heavy gold medals with the well-known motif minted – with different weights, but all of them were multiples. We know of pieces of 40, 18, 15, and 13 ducats. We can be sure that he gave them to anyone who could be useful to him and his family. The higher the rank of the recipient, the more valuable the medal. The Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna has two pieces of 40 and 15 ducats. The first was certainly a gift for a member of the imperial family, perhaps even for the emperor himself. Auction 424 offers the second-heaviest medal type of 18 ducats in extremely fine quality, which was certainly also a gift for a high nobleman. Johann Philipp managed to gain the favor of Joseph I for his family. The cardinal and diplomat died on 20 October 1712, not in his prince-bishopric in Passau but on a diplomatic mission in Regensburg.

Leuchtenberg. Broad double taler, 1547, Pfreimd. Extremely rare. Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 6,000 euros. From Künker auction 424 (3 July 2025), No. 602

The Nephews of Johann Philipp of Lamberg – a Trip to Leuchtenberg

As Prince-Bishop of Passau, Johann Philipp had no biological descendants. But he did have nephews. He helped to ensure that the seven sons of his brother Franz Joseph were also adequately provided for. Most of them ended up working in the imperial service. One, for example, became Tyrolean Oberstlandjägermeister (hunt master), another became known as “Musikgraf” (music count) in the office as imperial court and chamber music director in Vienna.

The eldest son and heir apparent, Leopold Matthias, was most successful. He was the godson of Emperor Leopold and was one of the courtly playmates of Joseph I, who was the same age. The latter enfeoffed Leopold Matthias with the Landgraviate of Leuchtenberg when Max Emanuel fell under the imperial ban during the War of the Spanish Succession. We mention this because Künker’s auction 424 also features a collection of Leuchtenberg coinage, although none of these bear the portrait of a member of the Lamberg family.

Joseph Dominikus of Lamberg. 1723 taler, Regensburg. Very fine. Estimate: 250 euros. From Künker auction 424 (3 July 2025), No. 665.

Joseph Dominikus of Lamberg

Two of Johann Philipp’s nephews were to have ecclesiastical careers. Their uncle used his connections to help them both. After all, the older one could have died unexpectedly from illness or an accident, as this was not unusual at the time. In this case, backup was needed. However, Joseph Dominikus – the older nephew – outlived his young brother, which is why we will only talk about him at this point.

He first went to study in Rome, Bologna and Besançon. Unlike his uncle, he was ordained as a priest at a relatively early age – 23. This may have been at his own request, given that his life shows he was more interested in pastoral care than in diplomacy and power politics. Of course, Joseph Dominikus was also positioned in various cathedral chapters – Passau and Salzburg – in order to secure the next vacant bishopric. In 1712, he became Bishop of Seckau. Seckau was part of the ecclesiastical territory of Salzburg and thus a “secondary” bishopric that was awarded and controlled by the Archbishop of Salzburg rather than the Pope. The wait finally came to an end on 2 January 1723: pressured by the imperial electoral commissioner, the canons of Passau elected Joseph Dominikus as their prince-bishop by 14 votes to 9.

Joseph Dominikus cared for his congregation in a very different way. He saw his office as a spiritual obligation. During his 58-year term, he undertook 199 visitation trips to ensure that his “flock” had good “shepherds”. Nevertheless, he was extremely unpopular. This was due to his prudent financial policy. Rather than running up debts to finance large projects, he ensured that taxes were levied effectively and that government spending was tightly controlled and limited. This was bad news for local businessmen. They were not interested in the fact that Joseph Dominikus repaid the 150,000 guldens of state debt that he had inherited in no time. They were also indifferent to the fact that 200,000 guldens were in the state coffers when he died – despite the county of Neuburg having been acquired by Joseph Dominikus for more than half a million guldens. After all, his subjects would have preferred to see this money in their own pockets.

Joseph Dominikus of Lamberg. 1747 ducat as cardinal, Vienna. Very rare. Extremely fine. Estimate: 2,500 euros. From Künker auction 424 (3 July 2025), No. 664

Degrading Passau in the Hope of Personal Advancement

Joseph Dominikus was not popular with the cathedral chapter either, as he ceded much of Passau’s property to the archbishopric of Vienna in 1729. This was due to the imperial decision to expand the rather poorly provisioned Archdiocese of Vienna. Historically young, it was not as wealthy as the old-established Archbishoprics of Passau and Salzburg. The emperor demanded that Joseph Dominikus hand over a territory comprising 69 parishes. This resulted in a significant loss of income and benefices for Passau. And this money was the reason why it was so attractive to be a member of the cathedral chapter. Members received a share of the income and could provide relatives and allies with benefices.

Joseph Dominikus thus considerably reduced the Passau cathedral chapter’s power. In return, Passau was given permission to purchase the county of Neuburg for half a million guldens – although the emperor reserved the right to reclaim anything he desired. Additionally, the de facto dependency on Salzburg, which had long been completed but still existed on paper, was lifted.

This was a bad deal for Passau. The fact that Joseph Dominikus failed three times to become Bishop of Salzburg despite imperial support shows just how little the canons thought of him. Instead, in 1737 – nine years after the horse trade – the emperor made sure he became cardinal.

Joseph Dominikus of Lamberg. 6 ducats, 1753, on the occasion of his golden jubilee of priesthood, as cardinal, Vienna. Very rare. Very fine to extremely fine / Extremely fine. Estimate: 30,000 euros. From Künker auction 424 (3 July 2025), No. 663.

Joseph Dominikus’ numismatic significance today stems primarily from his very rare and magnificent 6-fold ducat issues, created in 1753 on the occasion of his golden jubilee as priest. He celebrated the occasion with great pomp. The medals were minted using taler dies and given to distinguished guests. Few ecclesiastical princes of the 18th century lived to such an advanced age as Joseph Dominikus. He died in 1761 at the age of 81, probably to the relief of the entire cathedral chapter. Unlike his uncle and grandfather, Joseph Dominikus never displayed a genius for power politics.

Nor did most of the other members of the noble family of the Counts of Lamberg. Over the coming centuries, the family gradually lost the political and economic importance it had gained during its heyday after the Thirty Years’ War.