Gold for Wallenstein

When Louis XII once asked his marshal what was needed in order to conduct war, the latter replied: “To carry out war, three things are necessary: money, money, and yet more money.” Albrecht von Wallenstein would surely have agreed with him. Already on his first excursion into the military world as a 21 year-old he realized that money was of the essence. Proudly, the young man had embarked from Hungary only to find himself tied to the sickbed with spotted fever and an injured hand a couple of months later from where he watched his regiment dissipating for want of money and rations.

Times had changed after all. While only a few decades ago, battles had been fought with 10,000 men maximum, the troops had multiplied. Needed were two pounds of bread, one pound of meat, as well as several liters of beer or wine, for every man every day. That required a lot of money, and the pay wasn’t even included yet. Wallenstein later wrote in a letter: “Unless the soldiers get decent supplies as soon as possible they will leave their quarters, in disarray, and take whatever they will and what I cannot refuse them, because they won’t be able to carry on living solely on water and bread.”

The tax system, however, was still in its early stages. Estates and lieges negotiated laboriously with the ruler what amount of money he was due to in the event of war – or not. It comes as no surprise, then, that attention focused mainly on money raising in the early 17th century, when it came to military enterprises.

Wallenstein had become aware of the close relationship between wealth and power quite early. So, when he had the chance in 1608 to marry a very rich widow, he did so and hence laid the foundation to his rise.

Albrecht von Wallenstein, c.1636-1641. Painting by Anthony van Dyck. Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen Munich.

Once Wallenstein owned estates in Moravia, his economic genius became apparent. In contrast to his contemporaries, he could see no sense in exploiting his subordinates. On the contrary: he had realized that a satisfied man worked better. As a consequence, he dispensed his peasants from socage service, allowed them to fell lumber in his woods and let them fish in his rivers. With his support, farming was modernized. And that got Wallenstein money, in fact so much money that even Vienna noticed where the emperor was publicly known as always being low on funds. Here, we grasp the reason for Wallenstein’s spectacular rise. Ferdinand II had miscalculated during his war with Venice. In February 1617, he had run short of money. He appealed to estates and lieges for arranging troops at their own expenses. Wallenstein was the only one who actually agreed to do that. His men were successful: the Venetians begged for peace. And Wallenstein had a foot in the imperial door.

There, even more money was required since the beginning of the Thirty Years’ War. Wallenstein had it at his disposal or, rather, he knew perfectly well how to get his hands on it. His idea was to get contribution from those places which hadn’t yet been weakened by the war. These contributions mustn’t to be so high that individuals would be ruined but high enough to supply the troops, and hence prevent the areas affected by war to be completely looted by marauding soldiers.

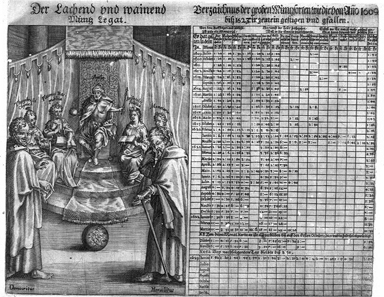

Broadsheet illustrating the inflation during the kipper-and-wipper period, c.1623.

A second, much more well-known idea to raise imperial money can be linked to Wallenstein as well. On 18th January 1622, Ferdinand II signed a contract in which he leased the coining right in Bohemia, Moravia and Lower Austria to a consortium and received the huge sum of six million gulden in return. One of the 15 contracting partners was Wallenstein. The worst ‘kipper-and-wipper’ period was following because recouping six million gulden with debase money, let alone realizing profit, was an enormous task. Golo Mann reckons that Wallenstein only managed to yield 20,000 gulden in one year-time. Invaluable, however, were the connections he had established during that time, because all of his contract partners ranged amongst the most important financial wizards back then.

It was them he owed a loan to that he needed to buy land which had fallen to the emperor by conquest. 9,000 square meters – that was the size of Wallenstein’s Duchy of Friedland where he founded cities and had a magnificent residency built, he modernized agriculture and created a model of industry that made him become one of the most powerful figures of the empire. Wallenstein’s influence wasn’t rooted primarily in his military wit but in his economic power that enabled him to accommodate the emperor with money time after time.

This extremely rare ten ducat piece of Wallenstein will be auctioned off in the next Künker autumn sale between the 7th and the 11th October 2013. The pre-sale estimate is 150,000 Euro.

Of course, Wallenstein, being ascended into high nobility, quite enjoyed the honors and privileges that came with it. His mint in Jicín where this gorgeous ten ducat piece had been minted, for example, he founded for prestige purposes only – or, as he had put it: “But I am doing it not for the benefit but for the reputation.”

In October 1625, Wallenstein was awarded the first contracts related to his mint. Mint master Benedikt Hübmer from Prague acted as advisor. On Wallenstein’s behalf, Hübmer manufactured several minting tools in Prague. In 1626, Wallenstein appointed mint master Georg Reick who decorated the coins with his sign, the sun with a human face, until 1630. That, however, was done without any official permission which was given only by the imperial privilege on 16th February 1628.

Georg Reich, the first mint master, didn’t stay long, though. He and his assayer were arrested in the second half of 1629 because it had come to light in the mint of Sagan that the ducats from Jicín didn’t contain enough gold. Wallenstein looked for another mint master. He entrusted his mint for a couple of months to the Wardein Heinrich Peckstein who passed it on to Sebastian Steinmüller in July 1630. His sign, the ascending lion in the circle, we find underneath the portrait on the splendid ten ducat piece illustrated here. By the way, the noble metal for Wallenstein’s coins were provided by some old acquaintances of him, back from the kipper-and-wipper era, Johann de Witte at first, then Jakob Bassevi. Together with him, these two had minted debased coins on imperial behalf.

Equestrian portrait of Wallenstein, copperplate engraving, no year. Original measures 35.3 x 26.6cm, c.1625/28.

The ten ducat piece depicts Albrecht von Wallenstein at the peak of his power. He is wearing the gorgeous suit of armor, the military mantle and the musketeer beard typical for this era. The legend on the obverse and the reverse translates: Albrecht, by grace of God Duke of Mecklenburg, Friedland and Sagan, Prince of the Wends, Count of Schwerin, Lord of Rostock and Stargard. Below the duke’s hat, the coat of arms assembles the most important of Wallenstein’s possessions. It is encircled by the Order of the Golden Fleece.

Wallenstein de facto was at the peak of his power in 1631, even though the emperor had ousted him from his office and sidelined him. While Wallenstein didn’t need the emperor, the emperor clearly needed him and rather urgently, as a matter of fact. After the victory of Gustav II Adolf near Breitenfeld, the whole of Germany shouted for the experienced commander.

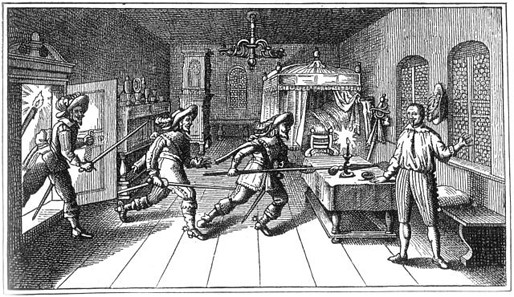

The killing of Wallenstein in Eger/Cheb in the Thirty Years’ War. After an anonymous contemporary copperplate engraving.

The fact that he possessed enough economic foresight as early as the end of 1632, after the Swedish king had died in the Battle of Lützen, to see the need for making lasting peace to prevent the country from being devastated for decades to come, ultimately cost him his life. After all, the time wasn’t ripe yet for people with such economic foresight, for people like Albrecht von Wallenstein.

The complete catalogue is available here.