The Year of the Freigeld in Wörgl

By

Who knows Wörgl nowadays? Yet for a short period of time the entire world looked at this small town. In 1932/3, one of the most successful economic experiments was conducted here that is still referred to when fairer forms of money are contemplated.

A response to the crisis of the 1930ies: the Schwundgeld

In the years after 1930 a new economic crisis afflicted the world. It did not result in inflation – quite the contrary: shocked by the hyperinflation of the German post-war era, the different states dabbled in a rigid austerity policy. The effect was that more and more people had less and less money at their disposal – they spent increasingly less money which led to a decline of demand which, in turn, resulted in layoffs depriving even more people of a regular income. It was a vicious cycle the politicians were not able to break.

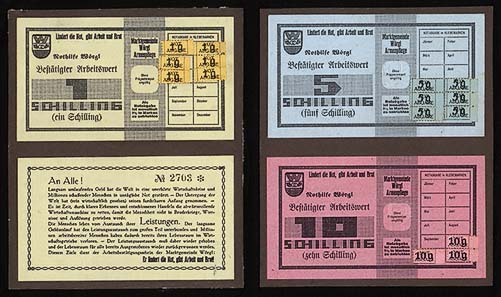

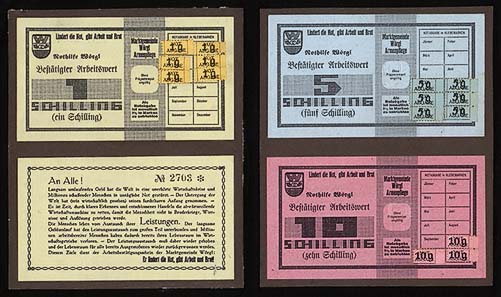

The labour certificates of Wörgl were issued in three different denominations: one, five and ten shillings.

At the same time, the instruments necessary to rethink were there already. In his works on Freiland and Freigeld, the theoretical economist Silvio Gesell had called for a “Natural Ecomonic System”. Although not all of his ideas could be put into practice, the Schwundgeld nevertheless gained many supporters. Gesell demanded money only as a means of exchange, unsuited for saving. To that purpose, he invented a currency that would not attract interest at the bank. On the contrary: to keep a note fit for circulation one had to affix a token to a fixed percentage of the total sum each month. To those unwilling to do that, only one option was left: to spend the note by the end of the month. The idea was to speed up the circulation of money with that surcharge and therewith boost the economy. The theory was soon put into practice: supporters of the German Freigeld established the barter society WÄRA in Erfurt in 1929, with relative success: only two years later, more than 100 German companies belonged to that society. What a spectacular success when the mining engineer Max Hebecker bought a dead mine with his WÄRA loan and reopened it. An entire town received employment and an income that admittedly was based on the Wära but worked extremely well on the local scale. In 1931 however, Hebecker was forced to give up and file for bankruptcy: for fear of the right of issuing banknotes, the German finance minister had categorically denied the State Bank the production, emission and use of any emergency currency.

The Wörgl Experiment

This was the situation when the railway employee and social democrat Michael Unterguggenberger became mayor of Wörgl in 1931. He faced a lost cause. An ever increasing part of the population was affected by unemployment. The cellulose factory was closed, the cement industry cut production and the Federal Railway of Austria dismissed many of her employees, too. Of the 4.200 inhabitants of Wörgl 400 were out of job. Every other already drew no unemployment benefits anymore to the result that the community had to sustain them.

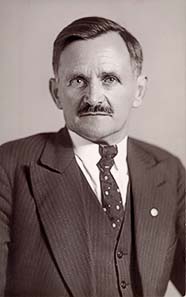

Mayor Michael Unterguggenberger (1884-1936), initiator and heart and soul of the Wörgl Experiment.

The high rate of unemployment resulted in a serious decline of municipal taxes. Numerous small businessmen were affected by the diminished purchasing power of the people of Wörgl and were forced to owe the municipal taxes. At the same time, the base rate had risen dramatically so that the community, with its ever falling income, was not even able to pay the interest on their bank credits anymore. Wörgl was on the verge of bankruptcy – not uncommon in the 1930ies. What was even worse than that: without money it became impossible for Wörgl to care for its unemployed properly. Real distress and the despondency to be rejected by the community spread among the proud Tyroleans. The economic misery was even worsened by the political stalemate. Twelve supporters of the bourgeois parties faced exactly the same number of social democrats which did not make governance any easier.

All in all, Unterguggenberger took over an almost insoluble task. But for the town of Wörgl that humble man was a godsend: he had ideas and the courage to put these ideas into practice even if that meant collaboration with the political opponent.

Before becoming mayor he has already made himself familiar with the concept of the Schwundgeld. When he came to power, the plan was pretty much worked out then. The biggest challenge was to win both party friends and political enemies over to the idea. Unterguggenberger resorted to an old trick: he got the opinion leaders on board to help him convincing the rest of the population. The priest, the head of the Heimatwehr, the headmaster of the community, some politicians plus three merchants and – especially important – the cafe owner agreed to explain the project in every detail to anyone interested. It was on July 5th, 1932, that a welfare association on a voluntary basis was brought into being: the community implemented a job creation scheme where the participants received their payments not in Austrian shillings but in labour certificates. These certificates could be bartered for goods at some shops – just like the real Austrian shillings. Other shops soon followed and in the end the new local currency became a real economy factor.

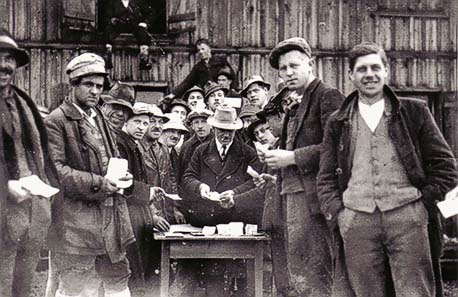

All those who participated in the job creation scheme received labor certificates.

Unterguggenberger announced that those labour certificates would be accepted as a means to pay the municipal taxes as well. To encourage a rapid circulation the labour certificates were designed as Schwundgeld: each month a token at a fixed percentage of the sum had to be affixed to the note to keep it fit for circulation.

A huge success

12.600 of the planned 32.000 shillings were issued as labour certificates – covered by the same sum in Austrian shillings deposited in a bank account as a pledge. And something miraculous happened: whereas an ordinary shilling achieved a turnover of 8.55 shillings per year – the community pays a worker one shilling, the worker later buys a coffee with that shilling, the cafe owner pays his sugar bill with it and so on – the labour certificates achieved 73 shillings thanks to the rapid circulation as a consequence of the depreciation. Only 1.3 shillings per community member were circulating in Wörgl but that prompted a change of mood. Suddenly, everyone was convinced that the situation could be changed for the better. Improvements in the infrastructure like a restructuring of the station forecourt or the construction of a bridge made it visible to all that finally something was happening! The project was widely accepted. News travelled fast; even abroad the “Miracle of Wörgl” as the Berlin newspaper “12 Uhr Blatt” called it on April 18th, 1933, was on everyone’s lips.

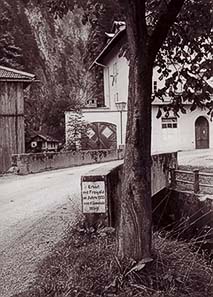

Thanks to the social scheme of Mayor Unterguggenberger a new bridge was constructed.

In Leipzig and Berlin, Paris, Budapest, Prague and Riga, in London, Arad, Basel and Zurich reports on the experiment were featured. In March 1993, even an important American financial newspaper published an article about Unterguggenberger. Journalists from all over the world travelled to Wörgl to see for themselves how the Freigeld worked – the small town witnessed a virtual tourism boom.

In the late summer of 1933, the community realised that already one third of the issued labour certificates was withdrawn from circulation by collectors – on the one hand, that was not the idea of the Schwundgeld, on the other hand the community did not consider it a problem at all since every certificate disappearing in a collection was a net income for the town’s treasury.

An experiment is terminated

Whereas the people of Wörgl were enthusiastic about Unterguggenberger’s scheme, the Austian State Bank did not consider the way in which it was circumvented amusing at all. As early as July 21st, 1932, i.e. before the scheme was implemented the State Bank took steps to stop the issue of the “bank notes”. But, the state captain of Tyrol outright refuses to carry out the orders of the Viennese Ministry of Finance. Unterguggenberger did not respond to a second order, this time given directly by the Federal Chancellery. He went through all judicial instances to save his successful scheme. But he did not stand a chance against the State’s claim to power. No surprise than, that the Wörgl news headlined “Free citizens or servants of the State Bank?”

On November 18th, 1933, with great international concern, the labour certificates of Wörgl were declared illegal by the Higher Administrative Court. The judge made it clear that he had only to assess the lawfulness of that scheme but not the question whether or not it was economically justified.

Unterguggenberger responded to the state sabotage with the following remarks: “I anticipated that my scheme would be prohibited in the end! I nevertheless did it because I wanted to show the world that it is possible! I have proven it both to me and the world! Now, this insight has to mature in the minds of the people! At first, the introduction of the railway was in danger of being banned, too!”

Unterguggenberger’s legacy

Unterguggenberger’s legacy has borne ample fruit although in most barter systems the Schwundgeld did not prevail. Yet a dream still lives on, a dream of a fairer world and a fairer currency available to the many and not to be monopolized by the few.

More information on the Freigeld at

www.unterguggenberger.org