Human faces, part 33: Il Moro and Leonardo

courtesy of the MoneyMuseum, Zurich

translated by Teresa Teklic

Why was the human head the motif on coins for centuries, no, for millennia? And why did that change in the last 200 years? Ursula Kampmann is looking for answers to these questions in her book “Menschengesichter” (“Human faces”), from which the texts in this series are taken.

Milan. Ludovico Maria Sforza, called “il Moro”, (1494-1500). Testone. Armour-clad bust of Ludovico to the right, above, on an escutcheon, frontal view of bust of Saint Ambrose of Milan. Rv. Crowned Milanese coat of arms to the left, staff with two buckets to the right. © MoneyMuseum, Zurich.

In 1482, Ludovico Sforza, regent of Milan, received the following letter of application: “My Most Illustrious Lord! Having now sufficiently seen and considered the achievements of all those who count themselves masters and artificers of instruments of war, […] I shall endeavour, while intending no discredit to anyone else, to make myself understood to Your Excellency for the purpose of unfolding to you my secrets, and thereafter offering them at your complete disposal, and when the time is right bringing into effective operation all those things which are in part briefly listed below: 1. I have plans for very light, strong and easily portable bridges […]. 3. I have also types of cannon, most convenient and easily portable, with which to hurl small stones almost like a hail-storm […]. 5. Also, I will make covered vehicles, safe and unassailable, which will penetrate the enemy and their artillery […]. 10. In time of peace I believe I can give as complete satisfaction as any other in the field of architecture […]. Also I can execute sculpture in marble, bronze and clay. Likewise in painting, I can do everything possible as well as any other, whosoever he may be.”

Francesco Napoletano, portrait of Ludovico Sforza, around 1494 (detail from the Sforza altar). Source: Wikicommons.

The author of this application was Leonardo da Vinci. Ludovico gave him the job and paid him 2,000 ducats annually for being at his disposal. Plus, da Vinci could expect to be richly rewarded if his works pleased the Duke. This did not simply secure his livelihood, with that kind of money, da Vinci could afford the lifestyle of an aristocrat. 2,000 ducats were the equivalent of 6,400 testones, like the one depicted above. Just to give you an idea: for 4 ducats, or roughly 13 testones, you could buy the coloured luxury edition of the Nuremberg Chronicle, published in 1493.

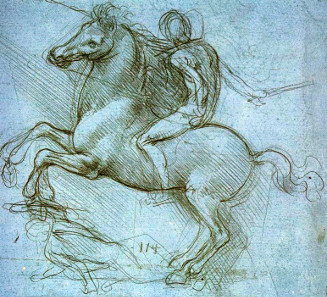

Da Vinci’s sketch for the Sforza monument, ca. 1488-1489. Source: Wikicommons.

While da Vinci was well paid for his work, he also had to put all his energy and talent into works commissioned by the Duke. He not only designed military equipment, but simultaneously worked on an equestrian statue of Francesco Sforza, portrayed the individual family members, played the lute, designed festive decorations, dresses, jewellery and whatever else was needed at court.

Da Vinci stayed at “Moro’s” court until 1499, when the French invaded Milan and drove Ludovico Sforza out. Da Vinci moved on and sold his art to whoever was willing to pay the most. His later years were spent in France, in the service of Francis I. Ludovico Sforza also spent his last days in France, however, not as a revered artist but as a prisoner of the king.

From “il Moro” to “il pontifice terribile”: in the next episode, we’ll move on to the machinations of Pope Julius II.

You can find all episodes in the series here.

A German edition of the book “Menschengesichter” is available in print and as ebook on the site of the Conzett Verlag.