Nudes at the Time of the French Third Republic

During the period of what is known as the French Third Republic, which lasted from 1870 to 1940, a group of medals and plaques were produced, which will be auctioned as part of the W. Risse Collection in the upcoming Künker eLive Premium Auction on 13 October 2021. In a collection entitled ‘Nuditas in nummis – Nudity and Eros in Numismatics’, Künker will be presenting 583 medals and plaques that all revolve around the naked human figure. Johannes Nollé has written the accompanying catalog. He presents readers with the historical and art-historical background of some of the most beautiful French works of this period.

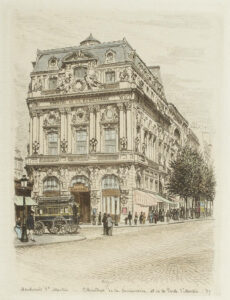

The Théâtre de la Renaissance designed by Charles de Lalande on Boulevard Saint-Martin in Paris is a typical example of French Eclecticism in architecture. The theatre was opened in 1873.

Many works of art from this period are difficult to assign to a particular style because the artists drew on many different ideas, blended them together and turned them into new works. This artwork exhibits characteristics from a wide variety of schools, including Historicism, Orientalism, Impressionism, Art Nouveau/Jugendstil, Surrealism and Art Deco. One important new development was that artists were frequently producing rectangular plaques alongside their round medals. This was probably partly due to the fact that the medal had been elevated as an art form, finding its place alongside sculpture and painting.

French artists increasingly drew inspiration from the nude paintings of the Rococo period, whose subjects are often depicted in the middle of a natural setting. The people of the Rococo period loved gardens. In this idyllic atmosphere, they believed they could rediscover the dreamland of Arcadia, created by ancient and contemporary poets. In this dreamland, one had a chance of encountering seductive water nymphs, goddesses or enchanting young shepherdesses, ready and waiting for some erotic escapades full of gallantry and romance.

These fantasies became more appealing in the decades preceding the horrors of the First World War, but they started to merge with some entirely new ideas and sentiments: rampant urbanisation, industrialisation and increasingly apparent environmental damage sparked a longing for the idyll of country life. Many French people withdrew to the countryside to recover from the economic pressures and political machinations of the monstrous ‘Moloch’ of the city.

César Isidore Henry Cros, Conservation des forêts, commissioned by the Société des Amis de la Médaille française, 1904. Only 220 specimens struck. Extremely fine to mint state. Estimate: 100 euros. From Künker eLive Premium Auction 356 (13 October 2021), Lot 8490.

This medal, made by César Isidore Henry Cros in 1904, reflects on the continuous destruction of the forests. On the obverse, it depicts the naked upper body of a young woman surrounded by a wreath of leaves – the fact that the artist used the leaves of the oak tree for this wreath is particularly notable. The oak has been considered a national emblem of France since the Celtic period. The inscription TERRARVM DECVS (= adornment of the earth) refers to the beautiful woman, whom we can identify as a forest goddess, and therefore to the forests themselves.

The reverse depicts a centaur attempting to pull down a gnarled oak tree, while the half-naked forest goddess tries to stop him. The medal’s inscription is quite unambiguous: SYLVAE SERVANDAE (= the forests must be protected).

Georges-Henri Prud’homme, Source et enfant pêcheur, 1904. Almost mint state. Estimate: 100 euros. From Künker eLive Premium Auction 356 (13 October 2021), Lot 8115.

The artistic imagination associated the sanctity of forests with the water nymphs who – as recorded in ancient literature – inhabited them. For example, Georges Henri Prud’homme depicts a fully naked water nymph in an implied forest. The nymph’s hand rests on a rock, from which a spring is gushing. The water cascades in small waterfalls into a pond, indicated by reeds.

On the reverse, a naked boy sits at the edge of a body of water, fishing. Fishing was a particular pleasure of country life. Claude Monet and other painters of the period featured this motif time and again in their artwork.

Water nymph paintings like Prud’homme’s are modelled after Ingres’ painting of a water nymph from 1856. Finding themselves in competition with painters and photographers, who were producing increasingly refined and provocative nudes towards the end of the 19th century, medallists were also inspired to create increasingly explicit works.

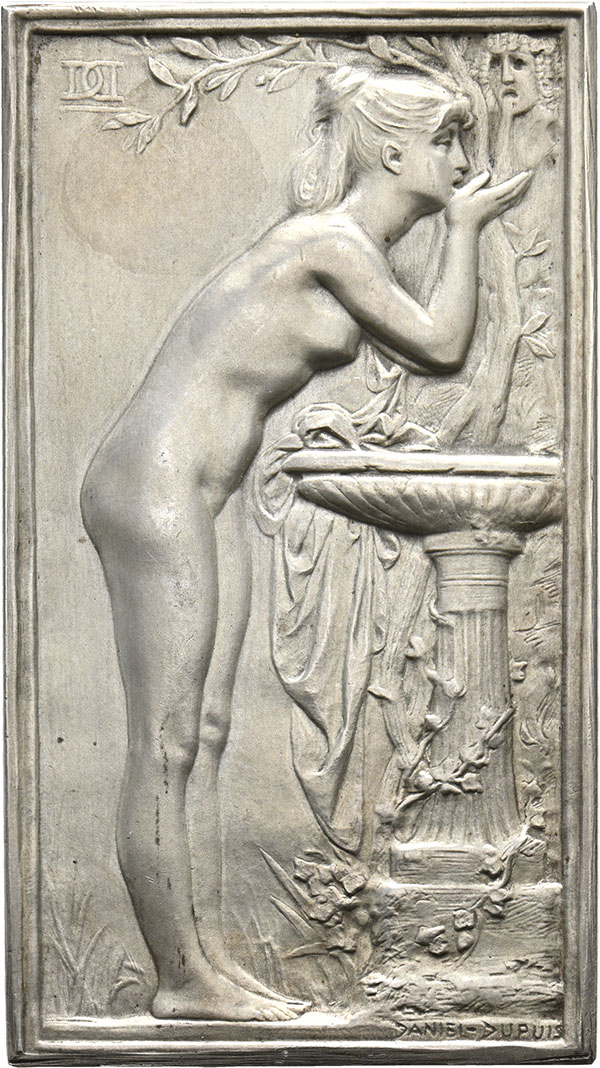

Jean-Baptiste Daniel-Dupuis, Chloë, 1899. Estimate: 300 euros. From Künker eLive Premium Auction 356 (13 October 2021), Lot 8021

It wasn’t just water nymphs that men were hoping to meet on a trip to the countryside: it was the beautiful country maids, who inspired erotic fantasies. Longus’ pastoral novel about the budding love between the young Daphnis and Chloë (whose name roughly translates to ‘the fresh green grass of spring’) was first popularised by the translations produced in the field of classical philology. Artistic adaptations of the story made it so famous that, even as late as 1975, Karl Lagerfeld was able to name a perfume after one of its title characters: Chloé.

The story also inspired Jean-Baptiste Daniel-Dupuis’ plaque from 1899. It depicts the naked Chloë standing before a fountain, her discarded dress lying on the edge of the fountain basin. She uses her hands to scoop up some water to drink. On the reverse, a winged cupid dips his finger into the spring water – representing Chloë’s awakening love for Daphnis.

Jean-Baptiste Daniel-Dupuis, Le nid, 1900. Estimate: 150 euros. From Künker eLive Premium Auction 356 (13 October 2021), Lot 8036.

These touching scenes were relocated to the groves and forests of the plaques. One plaque by Daniel-Dupuis, entitled ‘Le nid’ (= the nest) depicts a naked girl – we can assume she is a tree nymph – attentively watching a bird’s nest; on the reverse, we see a naked child feeding a bird. These medals evoke images of paradisiacal innocence.

Pierre Turin, La Baigneuse, 1927. Extremely fine. Estimate: 150 euros. From Künker eLive Premium Auction 356 (13 October 2021), Lot 8492.

The depictions of girls bathing, on the other hand, are rather voyeuristic. Though they may draw on ancient motifs, such as the Bathing Venus or Artemis observed by the hunter Actaeon, the bathing figures of the late 19th and 20th century are no goddesses. They are girls of the time, mostly nude models. They are reminiscent of the models of Pierre Auguste Renoir, who always presented variations on this theme in his paintings.

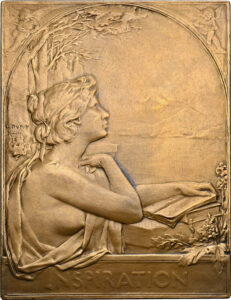

Georges Dupré, Inspiration, 1898. Extremely fine. Estimate: 60 euros. From Künker eLive Premium Auction 356 (13 October 2021), Lot 8468.

Many visual artists were increasingly using nude models, who were often more than just models. It wasn’t uncommon for them to be the artists’ own mistresses, sometimes even their muses, inspiring them to create grandiose works. This practice is recalled by one plaque by Georges Dupré. It depicts the portrait of a young girl, accompanied by the inscription INSPIRATION. The plaque was produced, as we can conclude from the inscription, in 1898 in Rome. After winning the Premier Grand Prix de Rome in 1896, George Dupré was permitted to work for a certain time at the Villa Medici and thereby perfect his craft by following the example of the ancient artists. The woman depicted here is probably based on a Roman mistress who kindled Dupré’s artistic creativity.

Alphonse Lechevrel, Hommage aux Graveurs, 1899. Estimate: 300 euros. From Künker eLive Premium Auction 356 (13 October 2021), Lot 8386.

The French medallists of this era were clearly aware of the status that their engraving skills held at that time. This double-sided plaque is particularly expressive. With it, the engraver Alphonse Lechevrel memorialised himself and his peers: the naked personification of the art of engraving – a beautiful nude depicted from behind – engraves the names of the most important engravers on a plaque suspended from an oak tree. Above this image, there is a banner bearing the Latin inscription ‘Magistris caelatoribus gloria in aeternum!’ (= the master engravers [or teachers in the art of engraving] shall be granted eternal glory!).

And these artists certainly earned that glory, with the works that we’ve had the pleasure to present to you here.

You can read an unabridged and unedited version of this article by Johannes Nollé in the August 2021 issue of the Künker’s customer magazine Exklusiv.

Click here to go straight to the eLive Premium Auction 356 ‘Nuditas in Nummis – Nudity and Eros in Numismatics – The W. Risse Collection’.

Are you interested to learn more about the sale? Here you can read a comprehensive preview of auction 356.

Would you like to receive the Exklusiv in future? Please contact the Künker customer service team.