Gold, Silver, the Morgan Dollar and the Rarest Silver Crown of the Latin Monetary Union

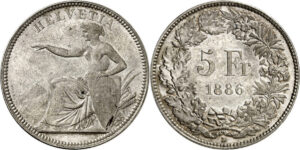

On 16 November 2021, Numismatica Genevensis will be auctioning a very important numismatic rarity. It is the rarest silver crown of the Latin Monetary Union. Only five specimens of this 5-franc coin from 1886 are known: three of them are located in Switzerland’s most important museums. Only two of them are in private hands. And now, for the first time since 2008, one of those two specimens is coming onto the market.

Swiss Confederation. 5 francs 1886 B, Bern. One of two specimens in private hands. One of five known specimens. From Auction SKA Bern 1 (1983), Lot 659. NGSA 5 (2008), Lot 1292. NGC MS64. FDC. Estimate: CHF 200,000. From Auction Numismatica Genevensis 14 (15 and 16 November 2021), Lot 395.

The estimated price for this piece, graded as MS64 by NGC, is CHF 200,000. The obverse depicts Helvetia against the backdrop of the Alps, a die created by Geneva-born medallist Antoine Bovy for the new coinage of the recently established confederation. The incredibly rare year can be found on the reverse, surrounded by a wreath of oak leaves and Alpine roses. The coin was minted in Bern, hence the little B under the wreath.

This coin not only holds significance in the world of Swiss numismatics. It is a key testament to the economic history of the 19th century, bearing witness to the close link between the silver deposits discovered in the American state of Nevada and European monetary policy, as well as the almost global transition to the gold standard.

Bavaria. Ludwig II, 1864-1886. 1 crown 1866, Munich. NGC PF63+CAM. FDC Estimate: CHF 20,000. From Auction Numismatica Genevensis 14 (15 and 16 November 2021), Lot 202.

A Groundbreaking Change in the Monetary System

For centuries, Europe used gold and silver to mint its coins. They were all appraised regularly, since their value fluctuated depending on how high the price of gold or silver was at the time. In order to keep these currency fluctuations off their balance sheets, merchants reverted to using a money of account, a system created in the Carolingian period. Any incoming or outgoing amount paid in cash had to be converted into this money of account for bookkeeping purposes.

And then came the 19th century. The people gained more power and demanded a currency system that even the simplest farmer would be able to understand. The money of account and the coins actually minted increasingly became one and the same. To make it easier for everyone to use these coins, the value was stamped on them right away, as illustrated by the Bavarian coin shown here: the inscription tells us that, in accordance with a coinage treaty, fifty such crowns were to be minted from one Cologne pound of gold.

The monetary system changed rapidly in the late 18th and 19th century. Each nation chose one single currency, whose value was fixed exactly. For example, the American Coinage Act of 1792 states that each dollar must be equivalent to 371 4/16 grains of pure silver. In its 1850 Federal Coinage Act, Switzerland postulated that its new single currency, the franc, should contain 4.5 g of fine silver, following the French franc.

The problem here was that it wasn’t just silver coins circulating in all these countries, but also gold coins, and the price ratio between gold and silver was constantly changing due to the many new gold and silver mines being discovered in the 19th century. The prices of precious metals were rising and falling more quickly than many governments were able to respond to them.

Gold from California, Silver From Virginia City

Just think of the California Gold Rush of 1848, when the discovery of gigantic amounts of gold caused the price of the metal to plummet. Here are a few figures to illustrate just how drastically the amount of gold in circulation changed after 1848: in the decade between 1851 and 1860 alone, 189.7 t of gold were mined. By way of comparison, this figure reached just 136.3 t in the half-century from 1801 to 1850, although it was already clear from 1849/50 that the price of gold was in free fall due to the increased mining output. That’s why Switzerland, for example, delayed its gold coinage until 1883.

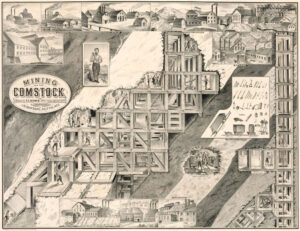

At that time, the price of silver was in free fall because the enormous yields from the Comstock Lode, located in Virginia City, Nevada, caused the world’s silver production to skyrocket to 2,544 t between 1861 and 1870. By way of comparison, this figure had been 772 t between 1841 and 1850, before rising to 1,760 t between 1851 and 1860. Between 1901 and 1910, 5,681 t of silver were mined around the world. And of course, this had an impact on the price of silver. Whereas in 1870, the London Fix price for one ounce of silver was 60 pence, it fell to 47 pence in 1890 and then to 28 pence in 1900.

Amount of gold mined annually worldwide (in tonnes):

| 1801-1810 | 15.3 |

| 1811-1820 | 10.3 |

| 1821-1830 | 14 |

| 1831-1840 | 20 |

| 1841-1850 | 76.7 |

| 1851-1860 | 189.7 |

| 1861-1870 | 167 |

| 1871-1880 | 157.9 |

| 1881-1890 | 158.2 |

| 1891-1900 | 314.3 |

| 1901-1910 | 567.8 |

Amount of silver mined annually worldwide (in tonnes):

| 1801-1810 | 888 |

| 1811-1820 | 535 |

| 1821-1830 | 455 |

| 1831-1840 | 590 |

| 1841-1850 | 772 |

| 1851-1860 | 1,760 |

| 1861-1870 | 2,544 |

| 1871-1880 | 2,069 |

| 1881-1890 | 3105 |

| 1891-1900 | 5041 |

| 1901-1910 | 5681 |

Impact on the Global Economy

What did this mean for the global economy? Each individual nation had to decide which metal they trusted to retain a certain level of stability. While India and China continued to rely on silver, Germany, when it first emerged as a unified empire with a single currency in 1871, opted for gold as the standard for its currency. To be clear: this didn’t mean that there were no longer any silver coins circulating in Germany, on the contrary. But the currency was defined in terms of gold and all denominations could be converted into gold at any time without any extra charge.

Therefore, a large proportion of the 6,000 t of silver contained in the coins that were withdrawn following the change in currency was reminted into German Reichsmarks. Of course, some of it also flowed into the global market. And that was an excellent excuse for all the silver barons in Virginia city, who were furious that their substantial financial investments were no longer paying off due to the dramatic drop in the price of silver on the global market. To put it into specific terms: between 1871 and 1885, the ratio between gold and silver fell from 1:15.51 to 1:32.6!

And by the way, the rumour that the monetary reform in Germany was solely responsible for the drop in the price of silver is still perpetuated in many numismatics books to this day.

Price of silver per ounce in British pence:

| 1870 | 60 |

| 1880 | 52 |

| 1890 | 47 |

| 1900 | 28 |

| 1910 | 24 |

Ratio of gold and silver prices

| 1871 | 15.51 |

| 1872 | 15.56 |

| 1873 | 15.95 |

| 1874 | 16.05 |

| 1875 | 16.54 |

| 1876 | 17.72 |

| 1877 | 17.24 |

| 1878 | 17.96 |

| 1879 | 18.31 |

| 1880 | 18.00 |

| 1885 | 19.45 |

| 1889 | 19.77 |

| 1894 | 32.60 |

The Emergence of the Morgan Dollar

This brings us to the measures taken by the U.S. government to help its silver producers. Richard Parks Bland, a lawmaker representing the state of Missouri, initiated a bill that would become known as the Bland-Allison Act. Nicknamed ‘Silver Dick’, Bland knew the major players of silver production and had seen their problems first-hand. In fact, the start of his career was directly linked to the Comstock Lode. So, he made their concerns his own and actually pushed through the Bland-Allison Act of 1878 – which went against the President’s veto, by the way. It stipulated that the U.S. Treasury should purchase 2 to 4 million dollars’ worth of silver in Virginia City every month. This silver was used to mint dollar coins, which have today become a very well-known and popular field of collection: the Morgan dollars.

A Conference in Paris in 1885

But let’s return to Europe. Here, the Latin Monetary Union was struggling to counteract the currency distortions caused by the overproduction of silver in America. Since it was established, the Latin Monetary Union had relied on bimetallism. In other words: the fineness of the coins minted under the agreement had to be such that the metal value of silver and gold coins remained at a fixed ratio of 1:15.1. But with the price of silver constantly falling, this was impossible to sustain. The price of silver was plummeting faster than the weight and fineness for new silver coins could be determined, the old ones could be withdrawn, or the new ones could be minted. That’s why the representatives of the Latin Monetary Union members, which also included Switzerland, met in Paris to discuss how they should proceed.

At the end of 1885, the delegates signed a treaty stating that the minting of silver coins should be suspended until further notice. In exchange, France promised to continue exchanging the currently circulating silver coins at face value into gold on account of the French Treasury. The Swiss representatives were able to negotiate a special arrangement for themselves: since Switzerland had seen colossal growth, both in terms of population and gross national product, and therefore had a lack of silver coins, it was granted permission to mint a disproportionately larger amount of circulating coinage in silver than the other member states. The official figure allowed was 6 francs in silver coins per capita – which would have amounted to 19 million francs –, but this figure was increased by 6 million francs to 25 million. Switzerland was also granted permission to remint 10 million francs’ worth of old 5-franc pieces into new 5-franc coins. The treaty entered into force on 1 January 1886, bringing us to the important 5-franc coin from 1886, which Numismatica Genevensis will be presenting in its upcoming auction.

A Broken Master Die and an Issue that was Never Realized

Whereas in 1884 and 1885, the Bern mint had only produced small-denomination coins from base metal, in 1886, it released an extensive issue of gold and silver coins. 250,000 gold coins were minted, in addition to one million 2- and 1-franc coins. There were also plans to mint 5-franc coins, but this failed due to a technical problem: the master die for the obverse broke, meaning that no new obverse dies could be produced. The newly produced 1886 reverse die had to be tested with old obverse dies before the official decision was made to mint the large-scale issue with new coin designs.

Although a competition was held in 1886 to select the new coin design, it wasn’t until 1888 that the design could be used to mint an extensive issue of 5-franc coins.

Thus, the rare Swiss 5-franc coin from 1886 is an historic piece that proves that globalization is not just something that has emerged in the past few decades. The rareness of this coin was caused by the same historical events that led to the prevalence of the American Morgan dollar, which was minted 6,400 kilometers away.

The statistics are taken from Michael North’s “Das Geld und seine Geschichte”. Munich, 1994.

To find out more about the negotiations within the Latin Monetary Union in 1885, see L. Amberger’s “Die Schicksale des Lateinischen Münzbundes. Ein Beitrag zur Währungspolitik”. Berlin, 1885.

The presented coins can be found in auction 14 of Numismatica Genevensis.

Read more about the origins of the Morgan Dollar and the circumstances in the “The Monetary History of the USA. Part 2”.

In the 19th century gold became the most important coin metal. Learn more about the circumstances at the time.