The People of Zurich and their Money 6: Can You Put a Price on Salvation?

by courtesy of MoneyMuseum

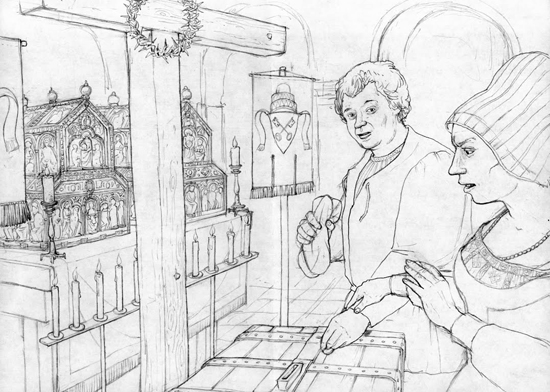

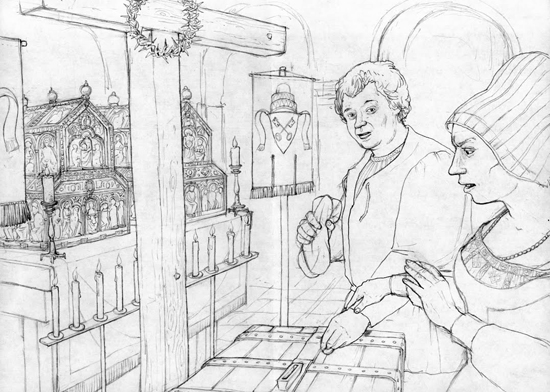

Our series ‘The People of Zurich and their Money’ takes you along for the ride as we explore the Zurich of times past. Around the year 1520, a woman from Zurich attempts to prevent her husband, a master craftsman, from buying an indulgence. Much like a good DVD, this conversation comes with a sort of ‘making of’ – a little numismatic-historical backdrop to help underscore and illustrate this conversation.

Ca. 1520. A woman from Zurich tries to keep her husband from buying a letter of indulgence. Drawn by Dani Pelagatti / Atelier bunterhund. Copyright MoneyMuseum Zurich.

Woman: Are you crazy?! Fork out the guldiner immediately! I won’t have the parsons filling their bellies with my money.

Husband: Dearest wife, it concerns my salvation. I can get this special letter of indulgence only once a year during the sacred week of Felix and Regula. I’ve already confessed and the priest has given absolution to me. And now I have the chance to pay for getting released from purgatory’s horrible tortures. One guldiner saves me seven years in purgatory, seven years for just a little bit of my money.

‘Little Money’! ‘Little Money’! Do you know how long we have to skimp for one guldiner? That’s nearly ten day’s pay! We could buy nearly a quintal of grain with this money! And you are talking of ‘little money’!

The priest told me that I should give him half a month’s wages for the letter of indulgence. Even one guldiner isn’t really enough.

Stop talking. These parsons are gobbling us up root and branch!

But it concerns my salvation.

Go and lead a pious live. Don’t go as often to the inn and don’t get drunk every evening. A student has explained to me that buying letters of indulgence is useless. There are enough churches, parsons and services! We’d do better to give our money to the poor. This is pleasing to God! – Those wax candles for example, yes, these twelve lights burning before the shrines …

(interrupts her) Aren’t they pretty?

Do you know what they cost during the year? The student has worked out that the wax costs as much as 19 1/2 Mütt of grain. Imagine, how many paupers could be fed with 19 1/2 Mütt of grain! We should get rid of these lights, and the pictures and statues of the saints should be also kicked out of the churches.

But that isn’t possible!

Nonsense, the student has translated a little Latin poem for me into our language, you want to hear it?

Did you burn oil and butter,

then the mice will say thank you.

They saw wonderfully all through during the night.

And this shouldn’t have happened.

Better you should have given the oil and the butter

To the poor, I would prefer that.

There oil and butter would be in a better place,

than lighting the night for the idols.

Are you sure that the Saints like the light?

They do not see anything, they are hollowed out behind.

Depiction of the Day of Judgement on the entrance portal of the Cathedral of Leon. Photo: KW.

Making of:

In the year 1336, Pope Benedict XII issued a constitution in which he laid out the Catholic position on which souls were eligible for entry into heaven. As well as the holy apostles, martyrs, confessors and virgins who belonged ‘in heaven, in the heavenly kingdom and celestial paradise with Christ, joined to the company of the holy angels,’ there was also room for those ‘who died after receiving Christ’s holy baptism’ and, according to the pope’s new constitution, those ‘who have been purified after death, if they then did need or will need some purification.’ With these words, the already widespread belief in purgatory was given official sanction from the highest of places.

Although the punishments equated with purgatory were perhaps akin to those of hell, purgatory and hell were not one and the same. While the lost souls of the hardened sinners would atone for their sins for eternity in hell, the time that a soul had to serve in purgatory was finite. In order to have a chance to go to purgatory and not to hell, it was necessary to have honestly regretted the guilt and to have been absolved of it by a priest. And then the sin had to be atoned for, either through time in purgatory or, and this was the preferred route of most people during the Middle Ages, through prayer and a donation to the church or to the poor, or through a pilgrimage.

In terms of making a donation, there were various options available. Firstly, one could make a donation, a one-time gift passed on to a church institution. Then there was the possibility of an endowment, a large sum of money or land ownership that would ‘forever’ ensure revenue and would finance good efforts that would help shorten the stay of souls suffering in purgatory. This is how, for example, more than half the funds needed for the wax that burned before the graves of the city’s patron saints Felix and Regula were generated – through tax payments from farmers who were working on goods that donors had bequeathed to the Great Minster specifically for this purpose.

There was also a third option that continued to gain more and more acceptance over the course of the 14th century – the indulgence. Despite the fact that the writings of the Protestant reformers may try to obscure it, the fact is that the indulgence was a popular and much sought-after means to clear the guilt of one’s sins. An indulgence proved beneficial both for the church institution, who was permitted to grant it with the permission of the pope, and for the faithful, who, for their money, could spare themselves a precisely defined time in purgatory.

Seller of indulgences. beginning of the 16th century. Source: Wikipedia. Ms. 351, So called Schembart book from the estate of Sebastian Schedel. Los Angeles, University of California, Library, Coll. 170.

The indulgence with which our audio drama is concerned had been issued by Pope Sixtus IV on June 12, 1479 at the request of Zurich Council. For five years, he bestowed upon every believer who had offered up and performed penance during the Felix and Regula week the same indulgence as if they had made the pilgrimage to Rome during the Jubilee year of 1475. Zurich council wanted to invest the money that was made therein for constructing churches, and the rebuilding of the Wasserkirche (Water Church) was particularly close to the town fathers’ hearts. After five years, this indulgence was converted into an ‘ordinary’ indulgence, whereby the believer could only earn forgiveneness for seven years of punishment in purgatory and an additional time period of seven quadragenes. The quadragene was to be understood as a sentence that could be satisfied by a penance of 40 days.

Anyone who wanted to obtain such an indulgence first had to display true repentance. Otherwise, donating the money was of no use. The sinner had to confess and was granted absolution of his guilt by the priest. During confession, the priest would specify just how much the poor sinner would have to pay. The rich would often be asked for the equivalent of 30 days’ work, while the poorer folk, and our fictional master craftsman would have been among them, had to pay a half month’s salary. The very poor who either sustained themselves through begging or simply earned so little that merely earning their daily bread used up their resources could offer prayer instead of monetary donations. Still, even the poorest of the poor were first expected to try to scrounge up the money by asking devout believers for a donation for this purpose.

Zurich. Guldiner 1512. The city’s patron saints Felix, Regula and Exuperantius. From Künker auction 217 (2012), 3073.

We can’t say with complete certainty whether the guldiner depicted here actually amounted to a half-month’s salary. Unfortunately there aren’t any sources available to us for the decade between 1511 and 1520 that would allow us to determine the daily wages of a master craftsman. For the period between 1541 and 1550, the daily wages can be estimated at 8 schillings, and so a craftsman would have had to work a good 4 1/2 days to earn one guldiner. Mind you, during the same period, the mütt (bag) (54 kg) of grain (= spelt-free crop) already cost 92 schillings and 6 pfennigs, so more than double what it cost in the years between 1511 and 1520. We would therefore hazard the estimate that the daily wages of our craftsman was half of 8 schillings, and that he would have had to work about half a month in order to earn one guldiner.

By the way, the poem’s contents are authentic, albeit adapted to modern language, although the poem actually came about somewhat later. It can be traced back to Utz Eckstein, who circulated it in a pamphlet in the year 1525.

It wasn’t just the selling of indulgences that afforded the church great wealth. Over the course of the Reformation, the city of Zurich promptly expropriated the Catholic Church. You’ll find out what happened next in the next episode, “the ‘pilfering’ of the church silver.”

You can find all other parts of the series here.

The texts and graphics come from the brochure of the exhibition of the same name in the MoneyMuseum, Zurich. Excerpts with sound are available as video here.