The Gold Standard Part 1: How and Why Gold Became the Most Important Metal for Coins

It actually all started with Sir Isaac Newton, or rather, with the huge gold deposits discovered in Brazil, and the trouble they caused him. These finds pushed down the price of gold in such a way that the established mint ratio between gold and silver coins had to be constantly recalculated. Even Isaac Newton – who was, at the time, master of the Royal mint in the Tower of London – failed to keep up with these developments. In his final adjustment in 1717, he valued the silver coins too highly. This effectively led to them disappearing from circulation.

Great Britain. George III. 1/2 Sovereign 1817, London. Rare in this condition. Nearly FDC. Estimate: 800 euros. From Künker Auction 340 (2020), No. 2777.

And so, England switched to the gold standard in practice long before a corresponding law was passed. It wasn’t until 1774 that parliament confirmed gold coins as legal tender. Silver coins only had to be accepted up to the amount of 25 pounds.

France. Napoleon. 20 francs AN 13 (= 1804/5) Q, Perpignan. Only 522 pieces minted. Nearly extremely fine. Estimate: 2,000 euros. From Künker Auction 340 (2020), No. 3340.

England therefore played a rather special role. In most other countries across the world, silver remained the metal of choice for minting coins. France, on the other hand, worked with bimetallism. Napoleon’s 1803 monetary law had established the long-standing legal mint ratio of 1 (gold) : 15.5 (silver).

Three Possible Options

And so, at the start of the 19th century, there were three possible options for a national currency:

1.) The gold standard

2.) The silver standard

3.) A mixed standard that uses both gold and silver, with a fixed rate of exchange between them

Australia. Victoria. Sovereign 1855, Sydney. Very fine to extremely fine. Estimate: 2,000 euros. From Künker Auction 340 (2020), No. 2585.

Price Fluctuations in the Ratio Between Gold and Silver

In 1848, gold was found in California; in 1851, it was found in Australia. This considerably increased the amount of gold mined around the world. While 15.3 tonnes had been mined worldwide between 1801 and 1810, this amount reached 76.7 tonnes between 1841 and 1850 and then climbed to 567.8 tonnes in the first decade of the 20th century. In other words, there was suddenly a lot more gold in circulation than there had been for centuries.

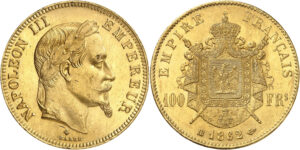

France. Napoleon III. 100 francs 1862 BB, Strasbourg. Only 3,078 specimens minted. Extremely fine to FDC. Estimate: 1,700 euros. From Künker Auction 340 (2020), No. 3767.

This caused problems for every nation whose currency, like France’s, was based on a fixed ratio between gold and silver coins. Some clever contemporaries used the exchange rate differences to make a hefty profit. They exported some here and imported some there, successfully lining their own pockets with a handsome profit. The result: at times, France had far too few silver coins, while the United States of America had far too few gold coins.

The enormous price fluctuations were therefore a disaster for lawmakers. No sooner had they established the ratio between gold and silver coins than the exchange rate changed and a new law would have to be passed in order to prevent losses for the treasury.

And it didn’t make matters any easier when, in 1859, a huge deposit of silver ore was discovered in Virginia City. The mines there would yield almost 7 million tonnes of pure silver by the time they closed. As a result, the price of silver also plummeted. In the long term, it fell from 60 p in 1870 to 52 p (1880) to 24 p (1910).

Great Britain. Victoria. Pattern for the Sovereign of 1839, London. Very rare. Extremely fine from Proof. Estimate: 2,000 euros. From Künker Auction 340 (2020), No. 2838.

Theory and Practice: Why Did the Gold Standard Prevail?

Researchers have established two different theories as to why the global economy ended up committing to the gold standard in the long term. One theory claims that people no longer wanted to live with the constantly fluctuating prices of precious metals. The other theory claims the cause is rooted in nations’ efforts to adapt their own monetary system to the nation with which they did most business.

Well, at the start of the 19th century, there were two nations vying for economic leadership: Great Britain and France. We know who came out on top. Thanks to industrialisation, London became the most important financial centre in the world. Two thirds of all world trade were financed by the pound sterling. Switching your currency to the gold standard therefore gave you privileged access to this financial centre.

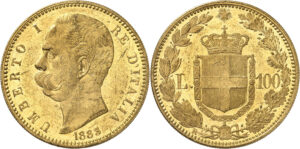

Italy. Umberto I. 100 lira 1883, Rome, in accordance with the specifications of the Latin Monetary Union. Only 4,219 specimens minted. Nearly extremely fine. Estimate: 2,500 euros. From Künker Auction 340 (2020), No. 2852.

France and the Latin Monetary Union

But France, with its bimetallism, was also a viable option. After all, the country had spread its monetary system during the Napoleonic Wars. There were French coins circulating in Belgium, Switzerland and Italy and vice versa. This afforded the advantage of a greater economic area, but also the disadvantage that each nation pursued its own agenda.

Belgium. Albert I. Pattern of 100 Francs 1911, Brussels, in accordance with the specifications of the Latin Monetary Union. Extremely rare. Extremely fine. Estimate: 50,000 euros. From Künker Auction 339 (2020), No. 2202.

Just think about when the Comstock Lode was discovered in Virginia City 1859 and its yield caused the price of silver to collapse. Italy was the first country in the French currency area to adapt to this development. In 1862, it changed the alloy used to make the circular blanks for its low-value coins, decreasing the silver content from 900 to 835 per mille – much to the annoyance of France, where coins were minted with 900 per mille. In other words: the aforementioned clever contemporaries imported French silver coins into Italy, had them smelt down and reminted there into more Italian coins of the same denomination and then reimported them into France to change into other French silver coins and so on.

In 1864, France found itself forced to drop the fineness of its coins to 835 per mille. But at that time, Switzerland had already decided to mint silver coins from an alloy of 800 per mille silver. And be sure those oft-mentioned clever contemporaries planned to do what they always did: they made a good profit at the expense of the general public.

France. Napoleon III. 100 francs 1868, Strasbourg, in accordance with the specifications of the Latin Monetary Union. Only 789 specimens minted. Extremely fine to FDC. Estimate: 2,200 euros. From Künker Auction 340 (2020), No. 3779.

The Latin Monetary Union of 1865 was actually nothing other than an attempt to make this impossible. Although some representatives at this conference lobbied vehemently for the gold standard, France prevailed with its bimetallic system. However, it failed to push the system through at an international level during the large monetary conference called by France in 1867. At that point, it became clear that there was no future in the bimetallic system.

Although the wonderfully colourful maps suggest time and again that the world was enthusiastic about the Latin Monetary Union, the fact that individual nations issued coins in the same weight as the golden 20-franc or silver 5-franc pieces did not mean that they wanted to preserve the bimetallic system. They simply wanted to have coins that were compatible with the French coins.

But in 1854 the pack was reshuffled as you will read in Part 2.

Here you can find the online auction catalogue, where the coins will be offered.

You can read the comprehensive preview of the Künker fall auction here.

And the developments after 1854 are explained in Part 2 of the article.