The great Ottoman monetary reform

On December 12, 2011, the Osnabrück auction house Künker sells the Sultan Collection of Coins of the Ottoman Empire. It is the spectacular result of 30 years of collecting. 908 lots reflect the history of coins of the last six Ottoman sultans. The decisive cut of course was the big monetary reform from 1845.

The sick man of Europe

It was the Russian tsar Nicholas I who, during negotiations with representatives of other European big powers, used this picture for the first time. Russia was like sick man who mustn’t be dropped. After all, a fall of the Ottoman Empire would have had unforeseeable repercussions for all.

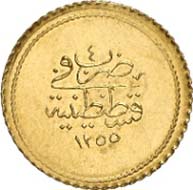

Yirmilik, Constantinople, 1255 H. (= before the monetary reform of 1845). Friedberg 13. From auction Künker 199 (December 12, 2011), no. 4. Estimate: 200 Euros.

The Oriental question – whether the Ottoman Empire was to be wiped out or not – was a key theme in the media in those days. The politicians remained cautious. England, France, Austria and of course Russia benefited from the powerlessness of the sultan. Each of the countries grudged the other a gain in territory, which naturally would have been easily achieved at the expense of the Ottoman Empire.

Mahmud II and Abdülmecid I

On July 1, 1839, Abdülmecid I took office. It was his father, Mahmud II, who already had realized that only a fundamental modernization would make sure that his house remained powerful.

Ceyrek, Constantinople, 1255 H. (= before the monetary reform of 1845). Friedberg 15. From auction Künker 199 (December 12, 2011), no. 9. Estimate: 75 Euros.

He had started a number of legal and military reforms – and had sent his son to France to acquire a modern education in the Western style. When Mahmud died, many of the reforms had been carried so far that his son ‘only’ had to implement them.

3 Kurush, Constantinople, 1255 H. (= before the monetary reform of 1845). KM 655. From auction Künker 199 (December 12, 2011), no. 16. Schätzung 150 Euros.

Thus, Abdülmecid became known as initiator of tanzimat (= edicts), a policy of rapprochement to the Western world. He reorganized the army, gave his empire national symbols, introduced a new civil code and penal law, founded a kind of parliament and the first universities, reformed the unfair tax system and worked on a more efficient administration. And, of course, under Abdülmecid a fundamental financial reform was carried through in order to counter the steadily declining money a new, stable currency.

The reform of paper money

As late as the reign of Mahmud II the Ottoman Empire had no common currency. Wages, prices and taxes were based on old calculation unit called Aqce. Foreign currency like the Maria-Theresien-Taler dominated daily life and money-changers made good business.

The system was complicated but well-practised so that the first priority was to make the population become accustomed to the new, uniform currency. State debentures (kaime) of 500, later of 1000 piaster, were put about, which were made attractive by an annual rate of 12.5 %.

This paper money was intended to yield the means required for the comprehensive reforms as well.

500 Kurush, Constantinople, 1255 H. (= 1845, since the monetary reform). Friedberg 16. From auction Künker 199 (December 12, 2011), no. 24. Estimate: 5,000 Euros.

250 Kurush, Constantinople, 1255 H. (= 1845, since the monetary reform). Friedberg 17. From auction Künker 199 (December 12, 2011), no. 26. Estimate: 3,000 Euros.

The monetary reform

Base on the French model and the Latin Monetary Union, the Ottoman Empire adopted a bimetallic system, hence a system based on a stable relation of gold and silver coins.

100 Kurush, Constantinople, 1255 H. (= 1845, since the monetary reform). Friedberg 18. From auction Künker 199 (December 12, 2011), no. 30. Estimate: 300 Euros.

The 100 Kurush piece of 100 piaster was introduced, known as Livre turque. Theoretically, it weighed 7,216 g, had a fineness of 916 2/3 / 1000 and hence contained 6.61 g fine gold. It was worth something in between the French 20 Francs piece and the British Pound.

20 Kurush, Constantinople, 1255 H. (= 1845). KM 675. From auction Künker 199 (December 12, 2011), no. 60. Estimate: 100 Euros.

Kurush, Konstantinopel, 1255 H. (= 1845 nach der Münzenreform). KM 671. Aus Auktion Künker 199 (12. Dezember 2011), Nr. 85. Schätzung: 400 Euro.

Second main denomination became the Medschidije in silver with a weight of 24.055 g and a fineness of 830 / 1000. Fractions were edited in silver of 10, 5, 2, 1 as well as 1/2 Piaster.

40 Para, Constantinople, 1255 H. (= 1845). KM 670. From auction Künker 199 (December 12, 2011), no. 94. Estimate: 400 Euros.

Copper coins were available of 40, 20, 10 and 5 Para, with 40 Para equating a Medschidije.

The new Ottoman mint near Topkapi Palace in Istanbul. Photograph: Gryffindor / Wikipedia.

The coins were produced by French and English minting technicians in a new mint, operated by steam power and equipped with English machines that had been built below the Topkapi Palace.

The person mainly responsible had stayed: mint director Düzoglu Agop Celebi came from an Armenian family of mint masters whose clever actions had protected the rotten state finances from collapsing for two generations.

A big success – and a big problem

The new stable currency brought the international trade great relief. Especially the foreign trade houses made lucrative business because the Ottoman Empire now received credit much more easily on the international finance market. That, however, wasn’t alone positive. Trade flourished, but at the same time debts increase. In the end, the Ottoman Empire put itself more and more into the hands of its creditors. In 1881, an international state debts administration had to be set up.

Anyone thinking of similar events in the present days may reach the conclusion that one might learn from history – when one is inclined to do so.

If you wish to bid on these coins, please click here.